Exploring the cinematic work of Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca

An interview on the artists’ practice and the intimacy of filmmaking

Working together for a decade now, Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca have been producing films and video-installations in dialogue with other artists connected to sound and stage. The duo has developed a research method based on documentary research and observation, but building the direction, the script, the costumes, and the soundtrack in a tight-knit collaboration with the protagonists of each project.

SOUTH SOUTH interviewed the artists to find out more about their work shown this year at the New Museum and Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP).

“Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: Five Times Brazil,” 2022. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum

“Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: Five Times Brazil,” 2022. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): Throughout your career you have been creating films and video installations featuring other cultural producers and artists. How would you describe the evolution of your practice?

Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca (BW & BB): With each film project, we have learned how to adapt cinema making strategies to the art form and context of where and with whom we are working. In other words, we have learned how to shape our approach in the films we make to the cultural producers and artists we are treating, rather than the other way around. Though we prepare the cast for the film set, there is also the need of adapting the cinema crew, as how they function to make an accurate portrait very much depends on their understanding of the nature of the artists and their art forms in the context in which they are working – be it through dance, poetry, song or theatre. They also need to take into account whether or not they are produced on the European continent or in South or North America, where our projects have taken place. To ensure a healthy relation between the professionals in front of and behind the camera, we often couple members from these communities with the cinema professionals we work with, in areas such as costume design, set production, cast preparation, make-up, and so on. This enables an accurate portrait through a real time exchange of knowledge to occur. As artists, we also learn with each film project new knowledge and strategies that often help with challenges the next film projects may bring.

The reception is equally important and can involve specific installation designs with elements that activate the spectator as an integral element for how to read our films. For example, in the installation of Swinguerra (2019), although the narrative structure of the film is the same on two synchronised screens, the shots, perspective angles and groupings of people vary. The spectator is placed in the centre between these two screens and must decide which one to watch, physically turning their view to engage with the other screen. Thus, they also engage in the space of the museum and with the other spectators. This expanded narrative cinematic space activates questions around subjective, objective, singular and plural viewpoints when engaging in the intersectional questions Swinguerra brings forth.

For the installation of Fala da Terra (Voice of the Land, 2022), bleachers for seating in the art museum mirror a specific theatre scene in the film where the audience also sits on bleachers. For a moment the two audiences, on and off screen, sit facing one another. The bleachers in the film are occupied by the survivors of the massacre de Eldorado do Carajás who are watching the theatre piece. They are witnesses watching a theatre piece which represents their struggle, and the audience becomes implicated as witnesses for this instance also.

“Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: Five Times Brazil,” 2022. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum

With each film project, we have learned how to adapt cinema making strategies to the art form and context of where and with whom we are working. In other words, we have learned how to shape our approach in the films we make to the cultural producers and artists we are treating, rather than the other way around.

SS: This year you had the first survey exhibition of your work in the US, Five Times Brazil. How do you think seeing your work in the context of the New Museum adds to or changes the meaning and intention behind the work considering the five projects focused on the socio-political context in Brazil and highlighted self-expression and resistance?

BW & BB: The exhibition Five times Brazil in the New Museum was, in fact, also the first time we saw all these films sharing a space together. To hear sounds from one film emanating from the background while watching another brought a more nuanced overlapping of themes which was a new experience for us. They forged new interconnections that we could only come to fully perceive after installing the exhibition.

The five films we presented were from overlapping research conducted over a decade which saw great political and social changes in Brazil, and given the spaces these films are set (the sports court, the nigh club, the church, etc.) we also recognised this is true to the reality of the urban spaces that brega clubs, Evangelical churches and public sports courts also share. The selection of films sharing an exhibition space mirrored the realities of these communal spaces in Brazil. The intention, however, was not merely to ‘represent’ these social spaces when showing them in the USA, but to draw the audience into the shared concerns that North Americans have. All of the artists in our films are forming communities, resisting, desiring access and acceptance, social ascendance and liberty where the struggle for equality towards belief, skin colour, gender, citizenship and land are all major questions.

“Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: Five Times Brazil,” 2022. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum

All of the artists in our films are forming communities, resisting, desiring access and acceptance, social ascendance and liberty where the struggle for equality towards belief, skin colour, gender, citizenship and land are all major questions.

SS: Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land] (2022) is your most recent project and had its national premiere at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP). How would you describe the creation of this film and the mechanisms you employ to engage with the work of Coletivo Banzeiros, a theatre group composed of members of the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement?

BW & BB: In previous films we were portraying artists of dance, song, poetry, where the distinction from ‘acting’ is clearer. With Fala da Terra we were coming closer to cinema in a complex manner; where theatre and cinema both involve acting at source. Pitfalls of adapting theatre to cinema needed to be overcome to remain focused on the concerns and struggles of the Landless workers’ Movement. The Coletivo Banzeiros were staging a theatre piece called ‘Por estes santos e latifúndios’ a Colombian play adapted to the local context and staged in Landless workers camps and settlements with the purpose of teaching younger generations about the oppressive forces at play in the region. For us to extend that drive to educate other audiences, we needed a rigour in maintaining a portrait of the collective in the context of their activism within the movement and place the acts of the piece they were presenting into the physical context of the region their struggles are based. Adapting to the methods of the ‘Theatre of the oppressed’ by Augusto Boal, who had worked closely with the Landless workers’ movement and still remains a tool for liberation in the movement, we decided to see the entire production of ‘fala da terra’ as an exercise in these terms.

As mentioned before, we have learned how to shape our cinematic productions to the culture we are treating, rather than the other way around. To work with the Landless workers’ movement – which is deeply rooted in a Marxist socialist framework – requires many discussions and collective decision-making processes before moving forward. These methods are not very distant to how we work in our projects where we must be very attentive to what our subjects are saying, doing and thinking about how they perceive themselves, their art and how they wish to be seen, in order to accurately create a portrait with them. With the Coletivo Banzeiros, the relationship of exchange and intention was very aligned. The collective and by extension, the network of Landless workers’ communities were incredibly generous, open and supportive. They understood very well the reason for making and distributing the film ‘Fala da terra’ just as much as they know the importance of the struggle against deforestation, extraction and agrotoxic monocultural farming, since they live and fight this struggle in a place they have seen

stripped and ravaged over decades.

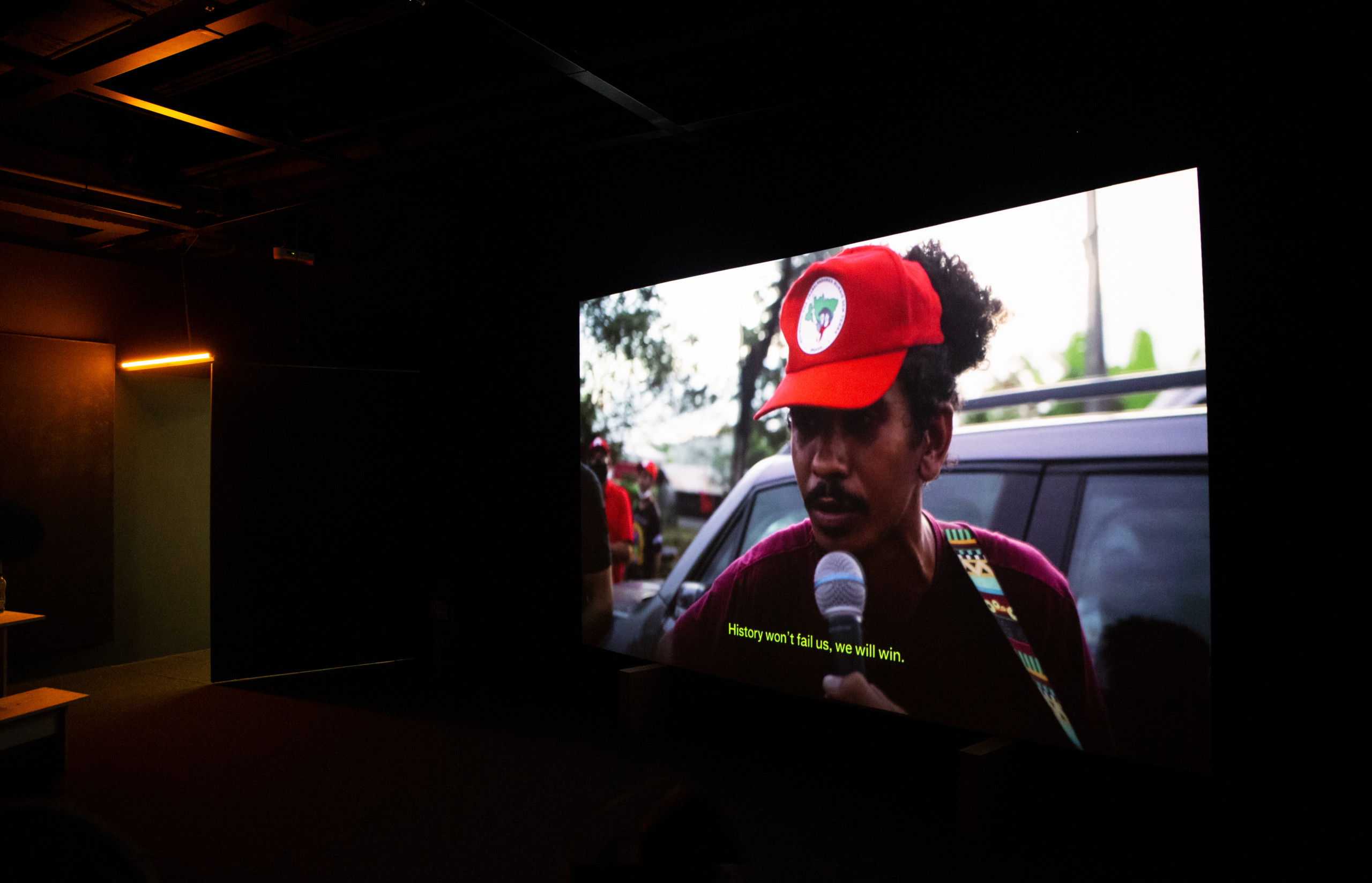

Installation view: Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land], 2022

To work with the Landless workers’ movement – which is deeply rooted in a Marxist socialist framework – requires many discussions and collective decision-making processes before moving forward. These methods are not very distant to how we work in our projects where we must be very attentive to what our subjects are saying, doing and thinking about how they perceive themselves, their art and how they wish to be seen, in order to accurately create a portrait with them.

SS: Why do you think it is significant to be showing this work at MASP?

BW & BB: The overall significance of showing ‘Fala da terra’ with The Landless workers’ movement in MASP is that we find ourselves at a very crucial intersection where Brazil, and indeed all of humanity, needs to decide which future we will opt for. Is it to be collective, agro-ecological, matrifocal, inclusive, respecting animal rights and nature, where education and art is the tool of freedom from the oppressive forces of capitalism’s addiction to fossil fuels, pesticides and mass production? Or are we to continue in its neoliberal drive for consumer fueled economic growth while committing ecocide for commercial return?

In Brazil, the image of the struggle of the ‘Landless workers’ movement’ has always been vilified by the media. As a result, their reputation in the urban populations of Brazil is akin to that of a terrorist organisation that steals land from its rightful owner where in fact, their strategies for occupying land are highly sophisticated and involve lengthy court procedures in order to have them awarded legally. The land they select for occupation is chosen through its misuse; Land that has underwent monocultural overproduction until barren and abandoned, land that has supported modern day slavery or other nefarious activities. Degraded by absentee estate holders, land is occupied and shared and brought back to productiveness by utilising agro-ecological systems in support of organic growth or reforestation in harmony with nature and wildlife.

Showing ‘Fala da terra’ at MASP occurred in the months leading up to the election between Luiz Inácio da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro. Embodied in these two candidates are the same decisions Brazil (and the world) must make for our future. It was important to show people that the Landless workers movement is not the enemy but the largest social movement in South America. The Landless workers’ movement is aligned with Da Silva who won the election. The world can breathe a small sigh of relief, but the struggle of the Landless workers’ movement continues, and we all need to understand their importance if we want a more just and equitable future for generations to come.

Installation view: Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land], 2022

The overall significance of showing ‘Fala da terra’ with The Landless workers’ movement in MASP is that we find ourselves at a very crucial intersection where Brazil, and indeed all of humanity, needs to decide which future we will opt for.

Top: “Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: Five Times Brazil,” 2022. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum

Bottom: Installation view: Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land], 2022

Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land], 2022

2K HD vídeo, cor, som 5.1 [2K HD video, color, 5.1 sound]; 20 min (Still)

© Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

Cortesia dos artistas e [Courtesy the artists and] Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro

CREDITS

Images supplied by Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro

Films included in Five Times Brazil were Fala da Terra [Voice of the Land], 2022; Swinguerra, 2019; Terremoto Santo / Holy Tremor, 2017; Estás vendo coisas / You Are Seeing Things, 2016; and Faz Que Vai / Set To Go, 2015