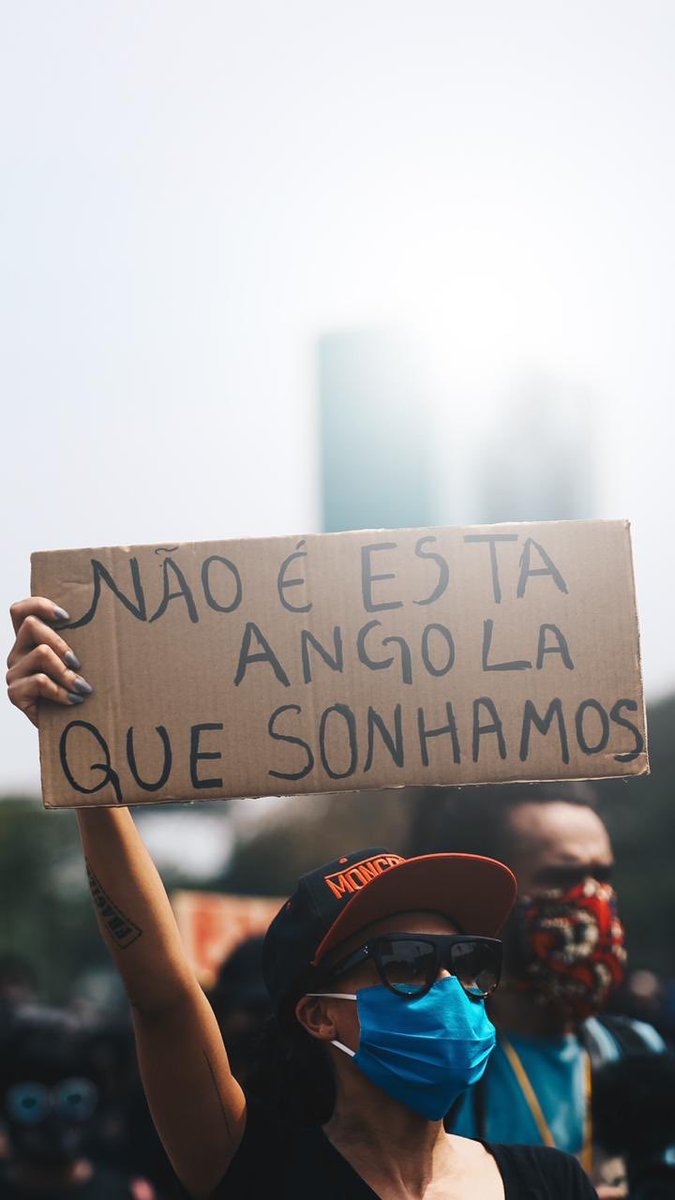

This is not the

Angola we dreamed of

Artists Helena Uambembe and Sandra Poulson exchange views on art, archives and the suppression of information in Angola.

What began as an intended dialogue between Angolan artist Sandra Poulson and South African artist of Angolan heritage, Helena Uambembe, evolved into a reflection on the nature of self-censorship by the latter. Both artists are concerned with the idea of the archive, what it is, and who authors it, addressing the gaps in the way the history of Angolans has been represented both in Angola and other parts of southern Africa. They are also both interested in how representations of current events continue to be suppressed, and what it means to protest in a vacuum. Like in various other parts of the world in 2020, Angola saw a dramatic uptick in both protests and police violence. The grievances were corruption, police brutality and unemployment, all the more unbearable than usual due to the raging and precarious coronavirus pandemic. Yet, in Angola – where inequality is rampant and freedom of information is quashed – reporting on instances of state violence is filtered and censored, and those speaking out about what is happening are tormented by fear. In response to this condition of self-policing and her exchange with a fellow artist, Helena Uambembe reflects on art, archives and the suppression of information in Angola.

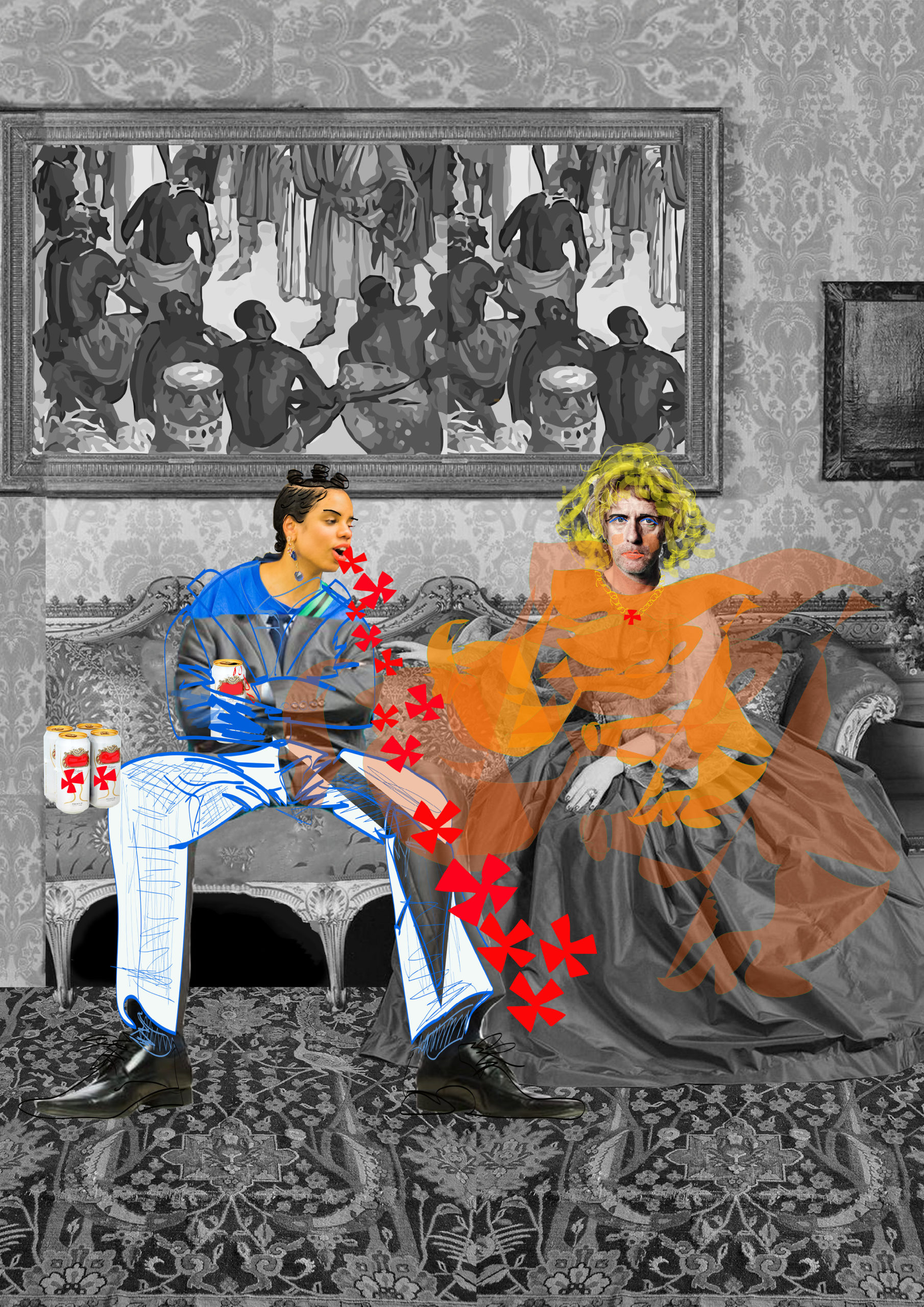

Sandra Poulson, An Angolan Archive.

Sandra Poulson, Puking Convo

In late December I had what was supposed to be a Zoom interview with Sandra Poulson to discuss the recent protests in Angola and our art. After listening to the recording of the interview, two words kept coming up: censorship and self-policing. “I often censor myself, not whilst I’m doing, but in the communication of what I do,” said Sandra.

Sandra describes herself as an artist, fashion practitioner, and Angolan. She creates questions, questions that may not have answers. Her most recent work, An Angolan Archive (AAA) looks at an assemblage of information in forms of text, video, voice recordings, drawings, installations and more. The work, although it is about Angola, is more focused on Luanda where Sandra is native. In the video work for AAA she hangs from two green structures, one with a dress and the other with a suit on. She attempts to wear these garments while climbing a ladder, as she hangs uncomfortably from the structures. She describes Luanda and the grey bricks of unfinished houses that symbolise hope. When I first encountered AAA on Instagram, Sandra described it as open ended, a work that anyone could inform. In that description I thought of my work, A luta continua… Ate Quando or The Ghost of my Parents’ past and where it fits in AAA.

An archive is described as a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place… or a group of people. Therefore the community of Pomfret in South Africa, where I was born, are an archive. My Angolan parents landed up here when they fled the civil war and my father became a soldier in the 32 Battalion, a military unit within the South African Defence Force mainly made up of black Angolan men. The work A luta continua… Ate Quando past is a nine piece photographic series that consists of me/my shadow posing as the leader of the Angolan Revolution. A luta continua… Ate Quando was a work that I struggled with; making it was heightened with emotions and feelings of rage and sadness. I was thinking of the Angola that my parents told me about in bedtime stories. In listening to their own drunken monologues, performances, I struggled because I would think of what Angola could have been and what it became. I was struggling because I was speaking to pictures of men, men who decided the fate of a nation so large and diverse.

Sandra Poulson, Puking Convo

I was thinking of the Angola that my parents told me about in bedtime stories. In listening to their own drunken monologues, performances, I struggled because I would think of what Angola could have been and what it became.

Helena Uambembe, Savimbi, Neto, Holden and I, 2019

In my struggle to make A luta continua… Ate Quando, censorship came up. In fact in the beginning of my research of the history of 32 Battalion, my collective partner Teresa Firminio (together we formed the artist collective KutalaChopeto) and I were cautioned by people from our home town of Pomfret that talking about that history is dangerous. That it is, they said, “like stepping on the snake’s head”. As KutalaChopeto, we discovered storytelling and myth-making as mechanisms of telling history, but this was also a form of self-censorship.

On the 11th of November, 46 years after Angolan independence, young protestors were met with rubber bullets and tear gas; cellphones were confiscated by the police, images deleted so they do not make the rounds on social media. All this, while João Laurenço, the president, was opening up a hotel on independence day during a pandemic when people are hungry, living way below the poverty line.

I write this in the comfort and safety of my home in South Africa, had I been in Angola it would have been a different story. My best response and contribution to the protest was sharing posts, live streams of the protestors on social media, bringing awareness to ‘what’s happening in Angola’. I asked Sandra what she feels activism looks like in Angola and she replied, “no matter the medium, be it art or otherwise, activism in Angola is being scared, but doing it anyway”

She went on to say that when we speak of Angolan anything you speak of politics – be it culture, literature, music, art or even healthcare. And that in a way you could speak politics through anything. When she made that statement, I recalled Rafael Marques, a journalist, who was found guilty of “abuse of the press, resulting in ‘injury’ to the president” in the Angolan Law on crimes against the state. As much as politics can be discussed through anything in Angola it can also be dangerous.

However if we want change in Angola, like Sandra said we have to do something even if it is with fear.

Image of a protester in Angola shared widely on social media, holding up a sign saying “Nao e esta Angola que sonhamos” (This is not the Angola we dreamed of.)

Left: Helena Uambembe

Right: Sandra Paulson