Sunil Gupta's latest solo exhibition titled 'Cruising'

Dates and Venue:

12 August – 16 September 2022

Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi

Vadehra Art Gallery presents an exciting collection of historical and newly commissioned bodies of work by pioneering photographer, writer, curator and activist Sunil Gupta titled Cruising. Gupta’s theatrical, often autobiographical interventions into topical cultural consciousnesses re-centre subjects such as racism, alternative sexuality, migration, queer issues and marginalia. Gupta explores the nature of conflict as expression and modality, engaging with historical, geographical and socio-political narratives that yield powerfully discursive, personally resonant and at times playful calls to action, enriching post-modern queer theory through his expressionist politics. SOUTH SOUTH interviewed the artist to find out about each series on show.

Sunil Gupta, Towards an Indian Gay Image – Saleem Kidwai and Me, Qutb Minar, 1983/2022

Archival inkjet print, 28 x 42 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

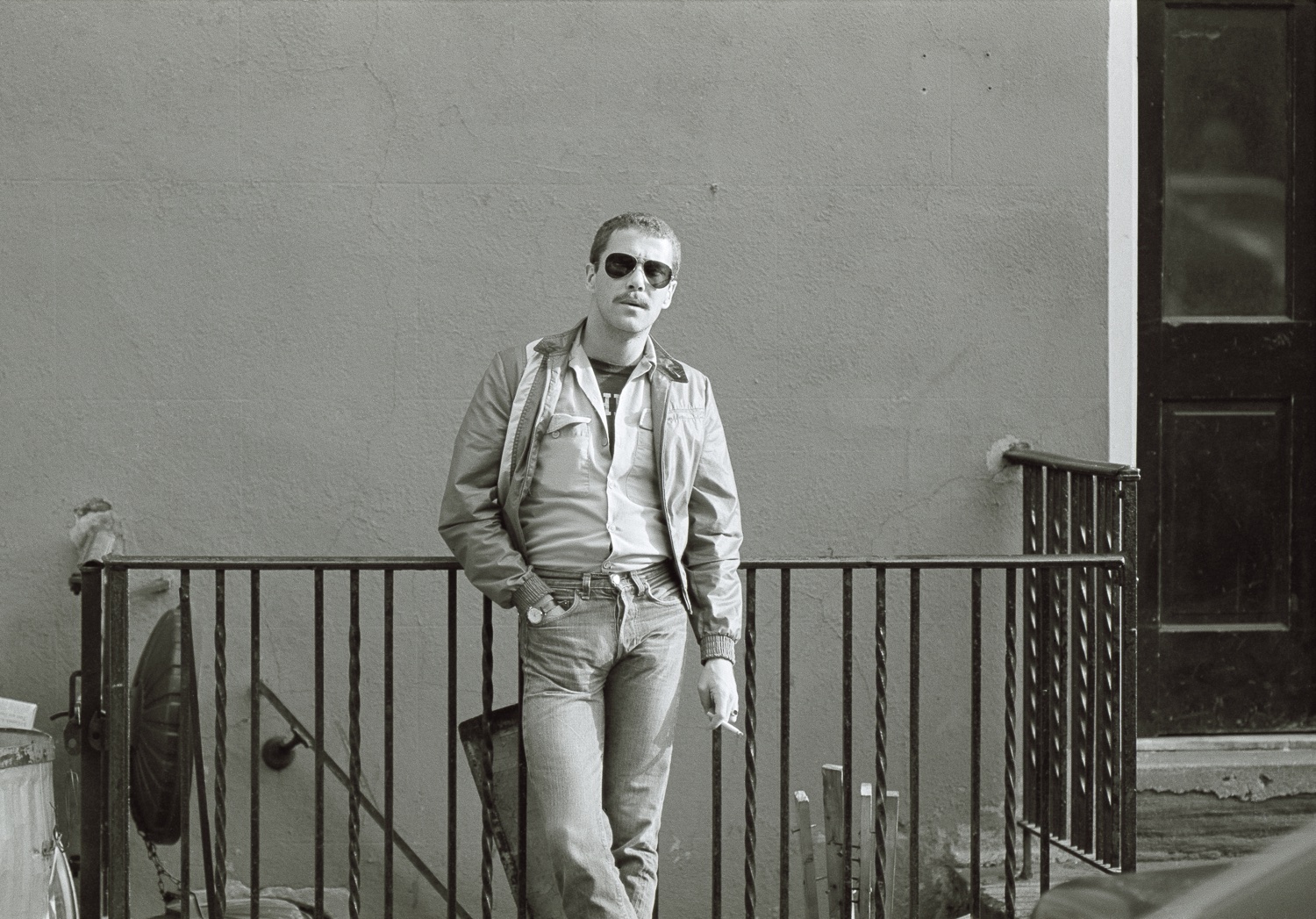

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #13 (Cruising 1960s

Delhi), 1982/2022

Archival inkjet print, 40 x 60 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): For this show you are including a selection of well-known series produced across decades that have been exhibited between Canada, the UK, Switzerland and India over the past two years. Could you share a thought about the background of each series for our readers who may be encountering these works for the first time?

Sunil Gupta (SG): Cruising 1960s Delhi is a curious one because it’s the second latest one. It has not really been shown before. So this is its first public showing in a print form. Although, Vadehra Art Gallery had it in an online form for an OVR in Art Basel in Hong Kong during COVID. But the actual prints have never been shown. What is curious about it is that the images are of a landscape. That I was shooting in 1980 when I first came back to Delhi from the west, in that case from London where I was then living. Here, I looked at a particular route that I followed as a young kid from the house that I lived in around the back of a very famous monument, a tomb of a Mogul emperor that was very well known as a kind of cruising site. And people were kind of making that discovery for themselves. Cruising here refers to going out into a space, going out into the world with the intention of meeting similar like-minded people who at that time didn’t seem to have a name. But it was somewhat away from the public, away from sight. So in 1980, when I shot this work, I was already in my late twenties, but I was remembering something from the 1960s. I took that opportunity to shoot it then because it still looked more or less the same. Not much development had taken place in the city. So this is a set of images that are a memory of a memory in the way and referring to my earliest encounters with gay public space, and not knowing that that was the terminology. It was just an exploration. That is the thing that is tying the entire show together.

Christopher Street was shot before Cruising 1960s Delhi in 1976, but again, not shown until much later in 2018 as a set of exhibition pictures and as a book. So it suddenly all came into the public realm. And so Christopher Street was very much about a kind of Western gay male cruising that took over a whole street and a whole neighborhood Greenwich Village in New York in the mid seventies after the Stonewall riot, which a lot of which the mainstream world likes to think of as the beginning of a gay liberation movement until till the beginning of aids, when there was a backlash. So that mid seventies was a euphoric in your face moment when gay men felt they could be out and proud and become very visible. So this homosexuality being under cover, only taking place in out of sight or in the dark or in alleyways and underground all suddenly came out, literally, and started to take place in broad daylight in full view on the streets. So that is what Christopher Street was documenting at the time. And I was documenting it again, not as researcher, but I was living the life. I was identifying very much with the people in the picture. I was just using my camera as a kind of shorthand way of meeting many more people than I would have if I’d stopped and talked to all of them.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #21 (Christopher Street Series), 1976/2022

Archival inkjet print, 24 x 36 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

Cruising 1960s Delhi is a curious one because it’s the second latest one. It has not really been shown before. So this is its first public showing in a print form.

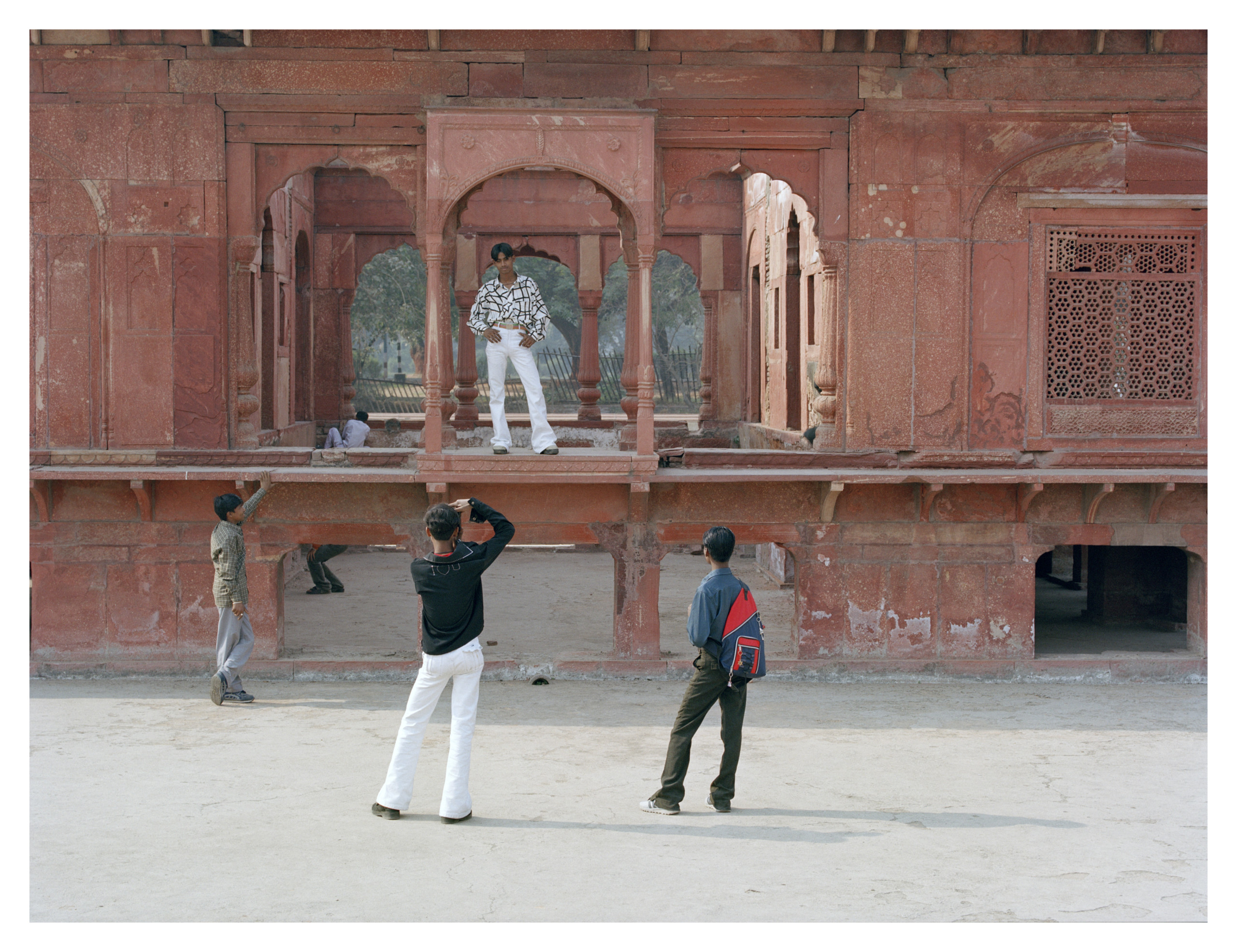

The next project is Delhi: Tales of a City which thinks of this city [Delhi], which is kind of my city in a way – my work is autobiographical – as having been a public space for a very long time. The medieval period was one of its highlights. I did some literary research about what travelers in this city had written about it; its daily life and the people who lived there, the shopkeepers, the tailors, the housewife, etc. From that I went to see what was left of the medieval city. It’s kind of still there. It’s very hidden behind all kinds of developments, further histories and certain erasure by British colonialism, the 1948 independence of India, etc. I wanted to remind us that this very public act of cruising that’s so central to gay life happened in metropolitan areas. Although we like to think of cruising, gay liberation and gay life as starting from the west, we did have it here in Asia. There were cities and, and therefore I’m claiming that there were similar stories in those earlier days happening here. We just don’t seem to have as yet as clear a record of it, particularly a visual record. So I wanted to explore that and the city in a more architectural way.

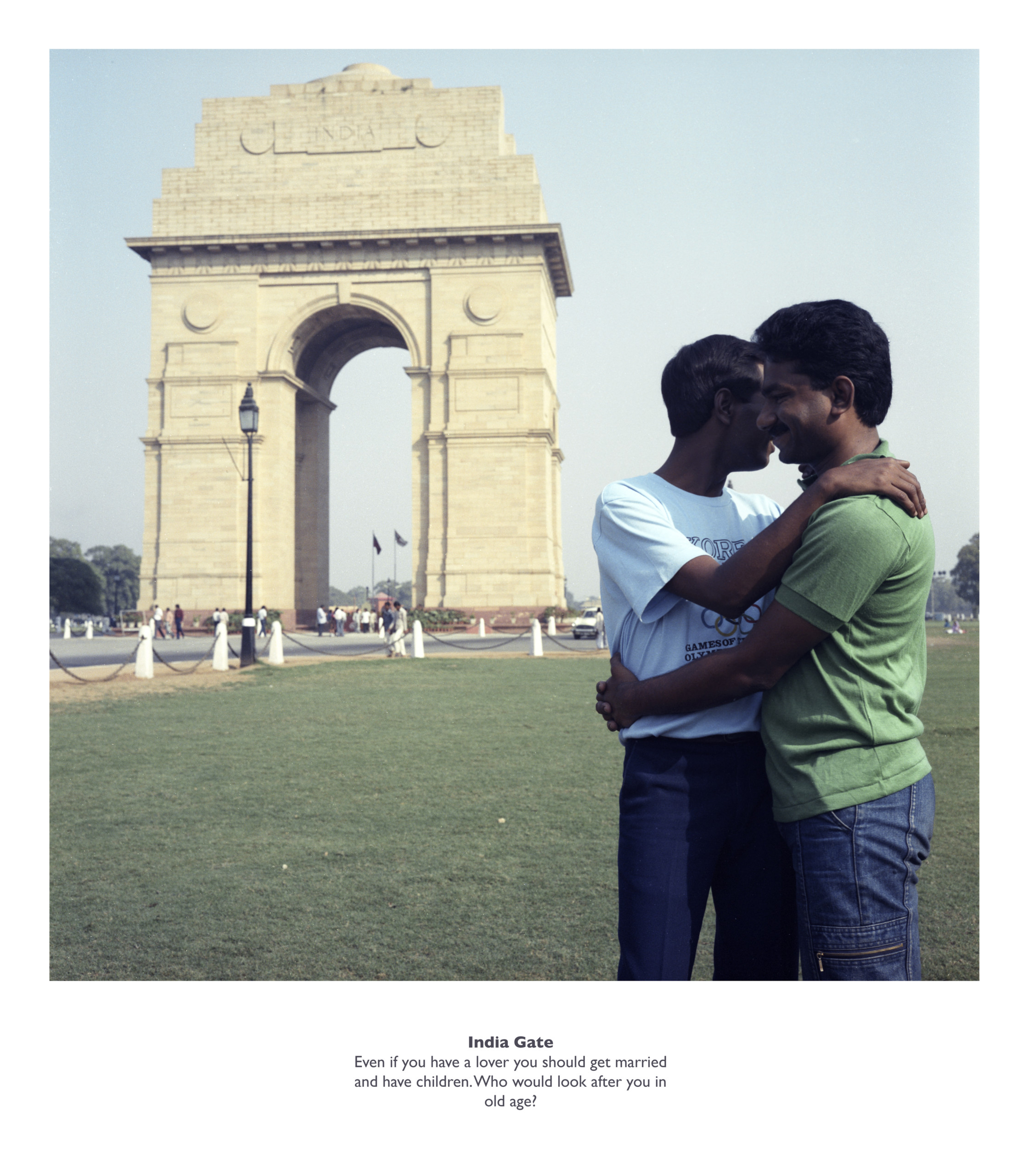

Towards an Indian Gay Image is a small collection of images that I made at the same time as Cruising 1960s Delhi in 1980. I was trying to make some kind of Indian gay photo image which was very elusive because nobody wanted to be in the pictures. Nobody who said they were gay wanted to be in the pictures and those who said they were gay, I wasn’t sure of they were gay in the way I understood it.It was confusing and difficult to figure out. I tried to do something. It wasn’t very successful, but I did make a few pictures. I decided to show them again. It is an older body of work. These works did not get much exposure. We have only now been showing it in the last few years partly because it’s a prelude to Exiles, which is another series of work that was made a bit later in 1987. But that was a more formal commission from The Photographers’ Gallery in London. So that needed to be produced and edited and presented as a formal body of work, which it was in 1987 and for which I again went back to these public places. I was very keen to insert the Indian gay men into artistry because I couldn’t find myself anywhere. It became a great motivational factor for me. So even though I couldn’t in all be ethical and do documentary pictures of what was going on, I decided to do this more directed photography where the place is real and the people are really gay Indian men, but we were all gathered together at each site to construct a picture that describes what cruising is all about. And you might wonder why it’s focused on cruising now. I just feel like cruising through the ages has provided a space for marginalized groups of people like homosexual men to find each other. It creates a space and it creates a community. What I’m arguing is that we only get community when people come together and even if the original reason they come together is for sex, the consequences are that you then have a community and that’s very important for further more political understanding of what gay identities might be beyond just having sex.

Sunil Gupta, Delhi: Tales of a City. Red Fort – 4, 2003/2022

Archival inkjet print, 24 x 40 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

I just feel like cruising through the ages has provided a space for marginalized groups of people like homosexual men to find each other. It creates a space and it creates a community.

SS: How do you feel about these works being shown collectively in New Delhi, particularly with some of their production having taken place in the city?

SG: We have come a long way in New Delhi from when I first showed pictures here about gay men in 2005. A lot of people came because of the novelty of it. I thought it wouldn’t be possible in my lifetime to have a gay public discussion in this society. So I was proved wrong in 2005, it was possible to show it. People didn’t come and shut it down but it was still illegal. So that law didn’t really change until 2018. So quite recently. There was this connection to South Africa in the changing of the law. South Africa changed it earlier and the arguments and the language used in the South African courts were borrowed by the Indian lawyers. India, like South Africa, has a constitution, so citizens have rights. Some citizens can’t have less rights than other citizens. That was the argument. But, of course, society always lags behind the law. The law changed, but of course, socially it is still not very accepted. I think fortunately, although India missed out on the gay liberation, LGBTI+ movements and all of that in those earlier times, it was just in time for queer theory and the queer moment. It’s been adopted widely through academia and there have been at least one and a half generations that are now coming out much like elsewhere in the world of young people, for whom it’s not a problem at all. They are very used to having discussions around gender diversity, the problems of binary sexuality, etc. I feel like this younger generation wants more. With them I think it is now possible to have more complicated exhibition projects discussing issues like cruising and not just who is sleeping with who and whether they are a man or a woman. I believe that there is a young audience that should be very receptive to the show in New Delhi today in a way that they would not have been 15 years ago.

Sunil Gupta, Exiles – India Gate, 1986/2022

Archival inkjet print, 24 x 20 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

I feel like this younger generation wants more. With them I think it is now possible to have more complicated exhibition projects discussing issues like cruising and not just who is sleeping with who and whether they are a man or a woman.

SS: Arrival is a new body of work that you produced in collaboration with photographer Charan Singh. This series touches on the thematics present in varying forms across your work (migration, queers issues, alternative sexuality, racism, marginalisation) and connects your activism. Could you please share more about the process of creating these works and unpack the key thematic threads present in this series?

SG: Arrival is completely new work. It is a commission that just went up in Birmingham. It was part of the cultural production that happened around the Commonwealth games. Charan Singh and I looked at LGBTI+ asylum seekers in the UK. We made life-sized portraits of them that were put up in a public street in Birmingham. We were trying to visually represent people who are suffering the consequences of a kind of colonial homophobia. The west has exported homophobia and colonial times the British empire created homosexuality as a sociological concept and spread it around everywhere. None of our societies had a name for it before. Along come these people, give it a name and then make it criminal the very next day. So suddenly you are called something and then you are put in prison. There is a modern version of this where American evangelical churches are spreading a lot of homophobia and financing it in vulnerable countries across central Africa, west Africa, east Africa as well as in Eastern Europe. So our subjects in this series come from many countries including Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania, Kenya, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Russia to name a few. So I felt with Exiles people were happy to leave the country physically. People like me didn’t feel like they could live here in the eighties because there was just no space to be gay publicly. And then if you did live here, you had to be completely underground.

I feel like with Arrival it happened to me when I went to the race of the teenager at 15, where suddenly my sexuality had a name. And it became a positive thing. I encountered collaboration at university. So similarly with these refugees that I’m meeting now, some of them have had really horrific experiences at home and they are kind of relieved to have arrived somewhere. They can express who they’re and people aren’t going to lock them up, torture them do corrective rape and on all that kind of stuff that goes on. So in that sense they have arrived in a situation where they can be themselves. It is the opposite of Exile in that, in a way, it shows the more positive consequence of having to leave. It is also a reminder that in some parts of the west, and to a certain extent in India now, and possibly in South Africa, things are improving. But in many parts of the world, things are not improving and the opposite is happening. Things are getting worse. So one has to constantly remain vigilant.

In addition to this, with this show I wanted to insert a collection of work that’s about more than people from India. Showing people from Russia and countries across Africa and other kinds of non-Indians who are also queer people cruising. Because when I meet them they are like my family even though they’re not Indian. I think we have to get away from being so biologically rooted in who we are.

Sunil Gupta, Arrival Series, 2022

Archival inkjet print, 31.4 x 42 in

Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery

With Arrival we made life-sized portraits of them that were put up in a public street in Birmingham. We were trying to visually represent people who are suffering the consequences of a kind of colonial homophobia.

SS: Could you share more about the title for the show and how it connects to the content addressed in each series?

SG: I think it [cruising] has become very relevant suddenly because we are losing the physical sites for this cruising activity to the internet. So people are now using dating apps rather than actually going out of their houses. I feel that’s not helping to create communities. That is actually making people more isolated from each other. And sure it might be a very convenient way to hook up and just to have sex, but it doesn’t seem to have other lasting qualities to it. We’ve now had this for at least 15 years or something, and people are starting to say that, just privately in conversations, people say, ‘really I’m very lonely actually.’ This is because they are just relying on the computer. They don’t really go out to meet real people. And also if you largely use this menu system, then you are in the typical internet straight jacket of just meeting a very particular kind of people. So you don’t meet all kinds of people that you think you don’t wanna meet, but actually if you met them, you might get on with them. So that’s one historical moment we’re living in.

Physical places are closing and know you see this in many places around the world. Bars are closing. Clubs are closing. Partly because of gentrification in the developed world and rents becoming too high. And partly because of the apps.

The other way it [cruising] is coming to the front of the discussion is via queer theory in academia. Queer theory, something that really came out of Yale in the late 20th century and very quickly expanded and became an academic theoretical place to also discuss these issues.

A lot of academic research is being undertaken around this notion of cruising and around cruising sites in the US in New York, but also in London. I would like to think this is also taking place in India and in South Africa. That’s why I think this is a good time to have a discussion about it.

Artist portrait. Image taken from the Vadehra Art Gallery website.

A lot of academic research is being undertaken around this notion of cruising and around cruising sites in the US in New York, but also in London. I would like to think this is also taking place in India and in South Africa. That’s why I think this is a good time to have a discussion about it.