Vivan Sundaram's solo exhibition titled 'Trash'

Dates: 22 April – 17 May 2008

Location: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai

Vivan Sundaram’s exhibition, Trash, develops a theme that he has engaged since 1997. Based on the economy and aesthetics of second-hand goods and urban waste, Trash recalls Sundaram’s installation, Great Indian Bazaar (1997), and carries over parts of his large exhibition living.it.out.in.delhi (2005).

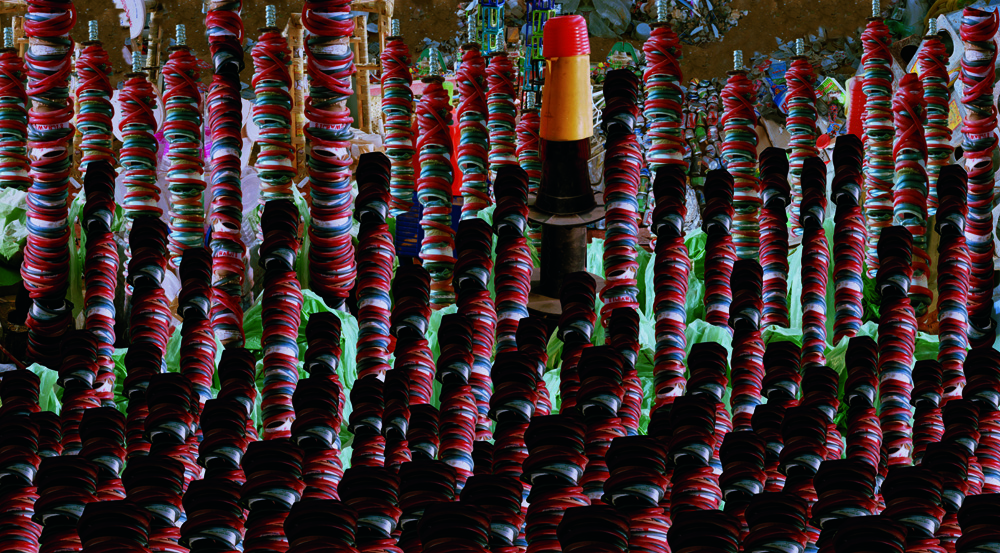

Vivan Sundaram, Barricade (with Coils), 2008

Digital Print

39.5 x 39.5 inches

100.3 x 100.3 cm

Edition of 10

Vivan Sundaram, Barricade (with Props), 2008

Digital Print

39.5 x 63.25 inches

100.3 x 160.7 cm

Edition of 10

In Delhi he had involved waste-pickers in the production of the last exhibition, working through Chintan, an NGO that enables this unorganized work-force to gain rights. Constructing a huge and fantastical cityscape with garbage in his own studio, Sundaram mediated the visual outcome via the camera from several vantage points. This continues to be explored in successive works included in this exhibition: the social implications of waste at the core of which is the frenzy of global consumption; a deconstruction of the commodity form that recalls modernity’s fascination with recycled objects; and the changing aesthetic of a key modernist procedure of bricolage.

The voluntary act of accumulating filth is a kind of indulgence, an excess. The colour and texture of industrial waste, dirty toothbrushes, plastic toys, tin cans and a sea of soiled milk bags, all of this makes for optical pleasure such as what the viewer might derive from a painterly palette. Among the photographs, there is a grand Master Plan, a surveillance view of a garbage-city; in Prospect, the same city is an urban conglomerate that recedes into an unsettling perspective. A set of photographs, titled Barricade, disorient the viewer by their scale: there are jammed edifices both frail and monumental, never-ending stretches of landfill, homes flattened by bulldozers and risen again. These photographs propose the material consequences of urban demolition, amounting at times to collateral damage of citizens’ lives.

Vivan Sundaram, Barricade (with Two Drains), 2008

Digital Print

39.5 x 86.5 in

100.3 x 219.7 cm

Edition of 10

This passes over into a deep melancholy when Sundaram stages an allegory of bare life. The soles of old shoes and their shadows make up 12 Bed Ward, a dark, dormitory-size installation about life lived below ground zero.

In the two-channel video installation, Tracking (2004-04), a camera focuses on a studio-set of another elaborately fabricated city, and the viewers glimpse a man and a woman—predators, or lovers– traversing the city by night. If Tracking reveals an archaeology of spent artefacts, ghosts and the artist’s dismantled sculptures, another recent video, Turning, develops what we may call a countering poetics. The rubbished fragments of a day-time city rise and fall, collapse and swirl. Towers blow over and topple in the wind and smoke one by one, structures big and small sway and whistle and turn askew. A text speaks of ascension, while yet another video, titled Brief Ascension of Marian Hussain, demonstrates that the flight can only be brief.

Trash continued its journey by being shown in the Biennale of Sydney, (curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev) titled, “Revolutions – Forms that turn”. He also showed work at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo in a show titled “Theatre of Life: Contemporary Art from India Today”, (curated by Akiko Miki).

Vivan Sundaram, Barricade (with Red Beam), 2008

Digital Print

39.5 x 100 inches

100.3 x 254 cm

edition 1/10

Installation view. Trash, 2008

Courtesy of Chemould Prescott Road

About the artist

b. 1943 in Shimla

Delhi-based Vivan Sundaram is one of India’s most pioneering veteran artists. His artworks span a variety of mediums and scales to address issues surrounding national modernisms, post-colonial identities, and third-world ideologies. Driven by archival and allegorical impulses, his bold political paintings, artistic collaborations, reckonings with his ancestry, and reflections on topical events, reveal his engagement with contemporary society, history, and memorialisation. As an ardent materialist, he has experimented robustly with pushing the boundaries of the picture-plane — he is India’s first installation artist.

Sundaram studied painting at MSU Baroda under KG Subramanyan in the early 1960s, following which he attended the Slade School in London as a commonwealth scholar where he was taught by the American artist, RB Kitaj. Deeply influenced by the 1968 protests in England, his early paintings embodied geometric abstraction as well as elements of kitsch and pop art, as they showcased his developing political imagination. In London, Sundaram also studied the history of cinema that led to his enduring interest in formal and conceptual qualities of film, influencing him to adopt principles of collage/montage. His painting, From Stan Brakhage to Persian Miniature (1968) for instance, juxtaposes elements from ostensibly incompatible registers of experimental cinema and miniature painting. It showcases his early interest in art history as well as his explorations of scale and perspective.

In the 1970s, Sundaram began investigating the ethical function of artistic representation while deliberating human struggle. The eponymous Heights of Machu Picchu (1972) features rhythmic ink drawings that accompany verses from Pablo Neruda’s poem, expressing solidarity with oppressed populations. Engaged in Marxist thought, Sundaram organised projects with the Student Federation of India and the All India Kisan Sabha. It was around this time that he also founded the Kasauli Art Centre (1976-91) and later the Journal of Arts & Ideas (1981-99) which provided platforms for artists and writers to experiment and collaborate. In 1981, Sundaram’s paintings were featured in the landmark exhibition, Place for People that highlighted the Narrative Figurative Movement in Baroda, where artists turned away from abstractionist tendencies of the time. The show encouraged Sundaram to address difficult themes in his practice, seen prominently in his lamentation of Delhi’s anti-Sikh riots in his exhibition, Signs of Fire(1984) at Gallery Chemould.

Sundaram travelled to Poland in 1989 where his visit to Auschwitz inspired his series, Long Nights (1989), dedicated to Holocaust victims. Continuing to probe historical concerns, the 1990s were a turning point in his practice. While responding to the Gulf War, Sundaram began working with unconventional materials. His Engine oil and charcoal on paper series (1990-91) contrasts charcoal smudges with burnt oil to explore surface and materiality. The work marks the beginnings of his transition to installation, photography, and video art. His experiments in Collaboration/Combines (1992) showcased at Gallery Chemould, Riverscape (1992-93), and House/Boat (1994) forged his pathway into a genre that could communicate his political preoccupations and conceptual instincts, powerfully. During these years, as a founding member of SAHMAT (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust), he also organised immersive works as a form of collective action to defend secular ideals. Through myriad mediums, found and ready-made materials, and archival sources, he has remained committed to reassembling the past into complex arrangements that place viewers at the centre of his works.

Installation view. Trash, 2008

Courtesy of Chemould Prescott Road

In his seminal installation, Memorial (1993), Sundaram responded poignantly to the destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya and its violent aftermath, raising questions about collective memory and citizenship. In a monumental site-specific installation, Structures of Memory: Modern Bengal (1998) at the Victoria Memorial, Calcutta he provided an alternative examination of the past by placing artefacts together in a cinematic montage. Meanings of Failed Action: Insurrection 1946 (2017) at CSMVS Mumbai, in which Sundaram collaborated with cultural theorist, Ashish Rajadhyaksha, explored contested narratives surrounding the 1946 Bombay Mutiny to highlight the event that has remained a historical blind spot.

Sundaram’s works have also re-examined his own family history — his video project, Re-take of Amrita (2001-02) manipulates photographs of Amrita Sher-Gil captured by Umrao Singh (Sundaram’s grandfather and Sher-Gil’s father) to consider questions surrounding artistic agency and relationships. It recalls his work, The Sher-Gil Archive (1995-6). In 2007, thes eries was displayed at the exhibition Amrita Sher-Gil at the Haus der Kunst, Munich and the Tate Modern, London.

By reinterpreting various archives and consistently building on his own works, Sundaram has continually reckoned with questions of human strife, mass-consumerism, and subaltern identities. 12 Bed Ward (2005) features rusty bed frames upholstered with soles of shoes to emphasise the plight of India’s rubbish-pickers. Themes of labour persist in works such as 409 Ramkinkars (2015), where Sundaram replicates the modern sculptor, Ramkinkar Baij’s iconic works such as Santhal Family (1938) and Mill Call (1956), using materials like motorcar parts, rubber pipes, and bicycles. He further explores the economy of recycled goods in his Trash series (2008) that constructs a utopian cityscape with garbage. The series deliberates global consumption, the use of found objects, and the aesthetics of bricolage. Further critiquing the excesses of modern life, Sundaram repurposes waste in his Gagawaka series (2011), creating uncanny sculptural garments that examine relationships between art and design.

Sundaram’s interest in found objects extends to archaeological material in works such as Black Gold, (2012) created for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale using ancient potsherds that recall those unearthed from the lost, riverine town of Muziris, a trading port known for pepper. In 2016, materials from Black Gold translated into his exhibition, Terraoptics, where they were reconfigured into small-scale sets, using LED torches and fibre optics. Through his fantastical reimaginations of the submerged town, Sundaram displays his relentless fixation with unearthing neglected or buried histories, whether they have been obscured through forces of nature or politics.

In 2018, Sundaram’s 50-year retrospective exhibitions, Step inside and you are no longer a stranger, at KNMA, New Delhi, as well as Disjunctures, curated by Deepak Ananthat the Haus der Kunst, Munich, traced the various turning points in his oeuvre as he has navigated and even steered pathways within the landscape of contemporary art in India. Staging immersive situations and spatial encounters, he continues using diverse materials, scales, and ideas to address themes surrounding history, activism and subaltern identity.

Top: Vivan Sundaram, Barricade (with Mattress), 2008. Digital Print, 38.75 x 67 inches (98.4 x 170.2 cm). Edition of 10

Bottom: Vivan Sundaram, Metal Box, 2008. Digital Print. 39.5 x 74.25 inches (100.3 x 188.6 cm). Edition of 10

Vivan Sundaram, Fly, 2008

Digital Print

60 x 39.5 inches

152.4 x 100.3 cm

Edition of 10

Vivan Sundaram, Prospect, 2008

Digital Print

104.5 x 59.5 in

265.4 x 151.1 cm

Edition of 10