Radhika Khimji at Venice

Unpacking the artist’s landscape of repetition and immersion created through works on show at Oman’s National pavilion

Radhika Khimji is one of the artists included in Oman’s first ever pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Curator Aisha Stoby identified the artist as one of Oman’s pioneers, alongside Anwar Sonja, Hassan Meer, Budoor Al Riyami and Raiya Al Rawahi, highlighting the significance of her presence in the pavilion. SOUTH SOUTH interviewed the artist to find out more about her practice and the work on show at Venice.

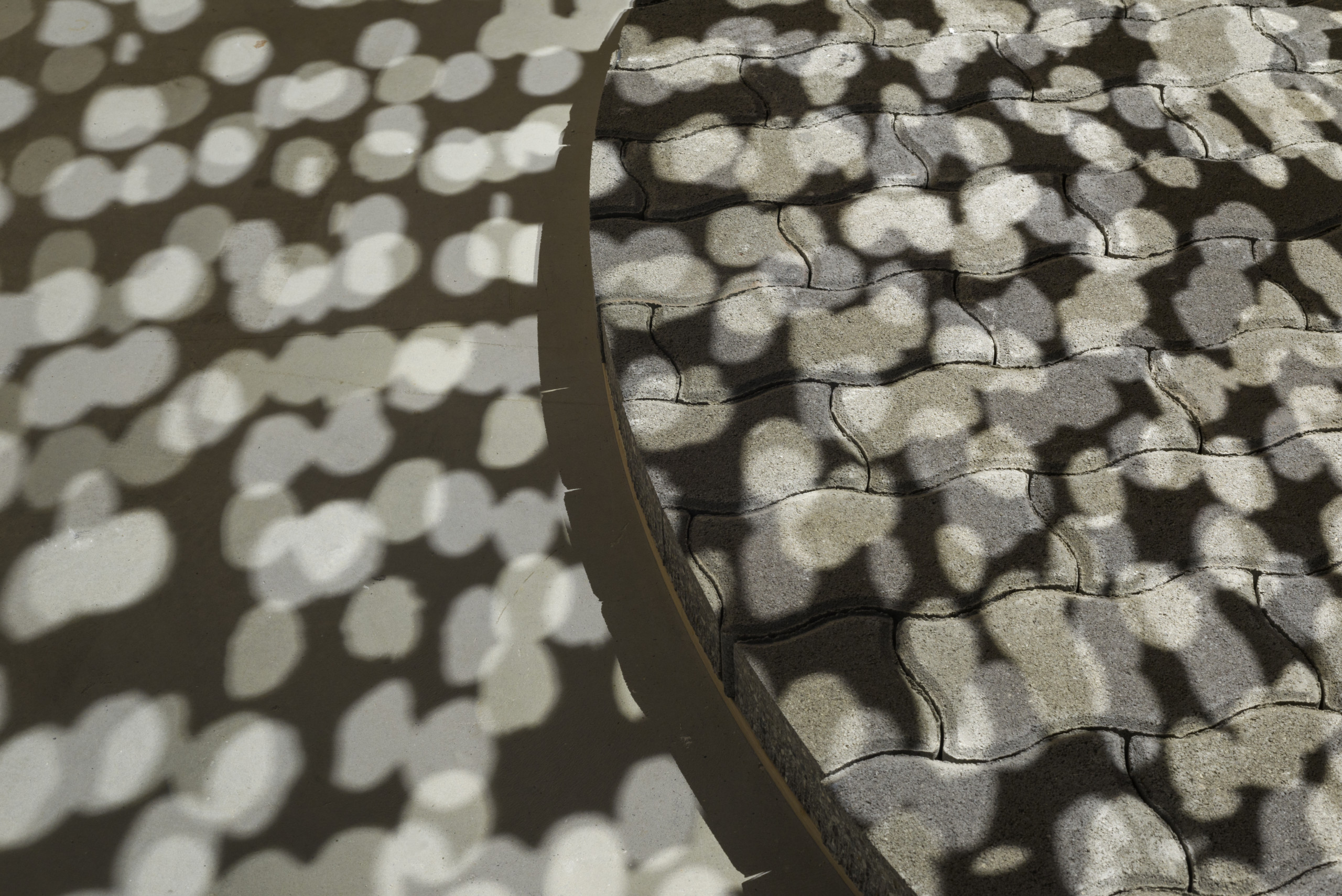

Install View, Oman National Pavilion, Arsenale at the Biennale Arte 2022 in Venice. Photo credit: Thierry Bal.

Images courtesy of Experimenter.

Install View, Oman National Pavilion, Arsenale at the Biennale Arte 2022 in Venice. Photo credit: Thierry Bal.

Images courtesy of Experimenter.

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): For our readers from across different regions who may be being introduced to your work for the first time, how would you describe your approach to art making and the evolution of your practice?

Radhika Khimji (RK): My work comes out of a making process, out of the fragmentary nature of collage and the continuous quality of working in notebooks. I am interested in what happens when different densities of mark-making meet, and the tensions in temporality when the slow process of mark-making covers a photographic image which was taken very quickly. There is a subtle push and pull between whether the object is a painting, a drawing or a sculpture, whether its identity is under question. There is always this need to evade the trap of identification.

SS: How do you think about the audience for your work? Does this influence your thematic references or the ways in which you present your work?

RK: I read some post-colonial theory while I was studying in University that really shaped my ideas about hybridity and identity in our world today. It made me question how I could talk about identity in my work without it becoming a formula for an artist of Indo-Omani ancestry working in the UK. It’s been a challenge to navigate these sticky points of loaded traditions, and not make them the central, easily digestible points of interest in my practice. I feel I consciously keep the registers and terms in flux to prevent any possessive and fixed interpretation. I am interested when the work can evade these terms, and somehow subvert a cultural reading of the work.

Install View, Oman National Pavilion, Arsenale at the Biennale Arte 2022 in Venice. Photo credit: Thierry Bal.

Images courtesy of Experimenter.

I am interested in what happens when different

densities of mark-making meet, and the tensions

in temporality when the slow process of mark-making covers a photographic image which was taken very quickly.

SS: You have a number of works on show at Venice, all a kind of combination of painting, drawing, collage, prints and sculptures in some way. How would you describe how they animate each other in the installation, and how would you describe the connection between these works both thematically and materially?

RK: These different elements work off each other and create a kind of charge. I hope there is a kind of momentum between the pieces, layers that get denser the longer you stay with the work. The dots and the repetitious geometric shapes add to this visual language which hinge off each other. The piece gets activated by the person looking and walking around the space, finding details and angles in the piece as it’s read in space. The works are both porous and opaque, tough concrete and soft fabric, hard wood and brutal aluminium, opposing registers that add to the tactile underground cave world where the blind fish live. The power of the gaze on one’s self, its threatening presence and cause of vulnerability are questions I ask myself in different cultures and climates – how does the gaze affect one’s agency? How is one destabilized? It was why I was so fascinated by these fish who could not see. I thought they were a poetic metaphor for the inability to have agency over sight and the pavement climbing up the wall added to this action of looking down and reflecting inwards. Walking without seeing.

SS: How do you think seeing your artwork in the context of the Venice Biennale, particularly within the Oman National Pavilion, changes or adds to the meaning behind the work?

RK: I definitely resonated with the work in Milk of Dreams. The themes of representations of the body and metamorphosis and the connections between bodies and the earth are areas I dwell upon in my practice. I’m always thinking about the body as an existential being and the blind fish an evolutionary apocalyptic symbol. Seeing my work within this framework made me readdress issues I have been contemplating around the body and landscape, environment and upbringing. Given the opportunity to represent these ideas within the Oman pavilion only highlighted how much I am rooted in the landscape of Oman and how much the work relates to its environment.

Install View, Oman National Pavilion, Arsenale at the Biennale Arte 2022 in Venice. Photo credit: Thierry Bal.

Images courtesy of Experimenter.

I hope there is a kind of momentum between the pieces, layers that get denser the longer you stay with the work. The dots and the repetitious geometric shapes add to this visual language which hinge off each other.

Install View, Oman National Pavilion, Arsenale at the Biennale Arte 2022 in Venice. Photo credit: Thierry Bal.

Images courtesy of Experimenter.