Roberto Gil de Montes in Venice

References to pre-Columbian and Huichol iconography make its way to La Biennale di Venezia through Gil de Montes

Roberto Gil de Montes is one of the two Mexican artists selected by curator Cecilia Alemani for the International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia for titled The Milk of Dreams, joining a list of 213 artists on show this year. SOUTH SOUTH interviewed Gil de Montes to find out more about his practice and work at Venice.

Roberto Gil de Montes, El Pescador, 2020

(Detail) Roberto Gil de Montes, Endangered Species, 2021

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): For our readers from across different regions who may be being introduced to your work for the first time, how would you describe your approach to art making and the evolution of your practice?

Roberto Gil de Montes (RG): I approach making art through sketching with ink, watercolor, and photography, to produce oil paintings. Sometimes I have a clear idea of what I want to paint, other times I use sketching and photography to explore. Once I have the idea in a sketch, gouache or watercolor I start painting in oil. I usually follow the sketched idea, but I find that if I remain open to changes that may arise as I paint, I am happier with the end result. It is important for me to have the discipline to show up at the studio and to keep a work schedule.

SS: How do you think about the audience for your work? Does this influence your thematic references or the ways in which you present your work?

RG: I don’t think of an audience for my work, I do paintings and I hope that someone likes what I do. I showed in the same gallery in Los Angeles for 25 years, and more or less knew who my audience was, but I also participated and collaborated in projects with other artists. One big audience for my work was the people who followed Mexican artists. I have been tagged as a Mexican artist, Mexican-American artist, a Hispanic artist, a Queer artist, and now Latinx, so I guess my audience, is somewhere in there.

Roberto Gil de Montes, El Pescador, 2020

I once met a Huichol man who was making gourds and masks decorated with images of peyote, deer, birds and other natural things. This experience multiplied the way I perceived my world. I found out that I enjoyed being disconnected… looking at land and seascapes that were virgin, undeveloped for ages.

SS: Bodies of water and greenery are frequently present in your work, often accompanied by references to pre-Columbian and Huichol iconography. Could you share more about the importance of these references in how you think about your work?

RG: Thirty-four years ago I was on a vacation in a small fishing town in the pacific coast of Nayarit, Mexico. I was impressed by how primitive it was, the town had only one phone, no television, no malls or large food markets, yet to me, it seemed that the people were happy. I began to see references to pre-Columbian ceramics of western Mexico, in their way of life. I met a Huichol man who was making gourds and masks decorated with images of peyote, deer, birds and other natural beings and things. This experience multiplied the way I perceived my world. I found out that I enjoyed being disconnected, I felt close to nature and enjoyed looking at land and seascapes that were virgin, undeveloped for ages. The life of fishermen, the Island, the Huichol, (Wixarica) and the jungle began appearing in my work, there is a rich amount of pre-Columbian artifacts in the area and I began to take an interest in finding their history.

Chicano artists use pre-Columbian images as a way to keep in touch with their roots, I was interested in pre-Columbian art as a teen, and began using pre-Columbian symbols as an artist in the Chicano art movement in Los Angeles.

Since my teenage years I have been interested in pre-Columbian art. Generally ceramics from all over the country, but later more specifically ceramics of western Mexico. Ceramics from western Mexico are funerary, I am attracted to the representation of the human figure in their environment in the forms of models, animals, birds and dogs. I have used the images sometimes literally in my ceramic projects and other times I draw inspiration from them. When I was in elementary school, we did a project in class constructing the eyes of god in yarn, the idea was taken from the Huichol culture. When I started visiting Nayarit, I was surprised to see the Huichol in their costumes selling beaded figures and decorated gourds. I befriended a Huichol (Wixarica, as they call themselves) and I did a project using real pre-Columbian figures that were broken, mostly torsos. I had no idea what to do with them so I asked my friend if he could decorate them with beads. I am fascinated by old yarn paintings that have a narrative. They compose their paintings in a personal or family base, but I use random narratives. Most of the artisan work of the Huichol is now a way for them to make a living, selling objects for tourists. They live in our town temporarily during the tourist season and then return home. Mostly they stay to themselves, women are shy, yet the men are more curious and it is easier to establish conversation with them.

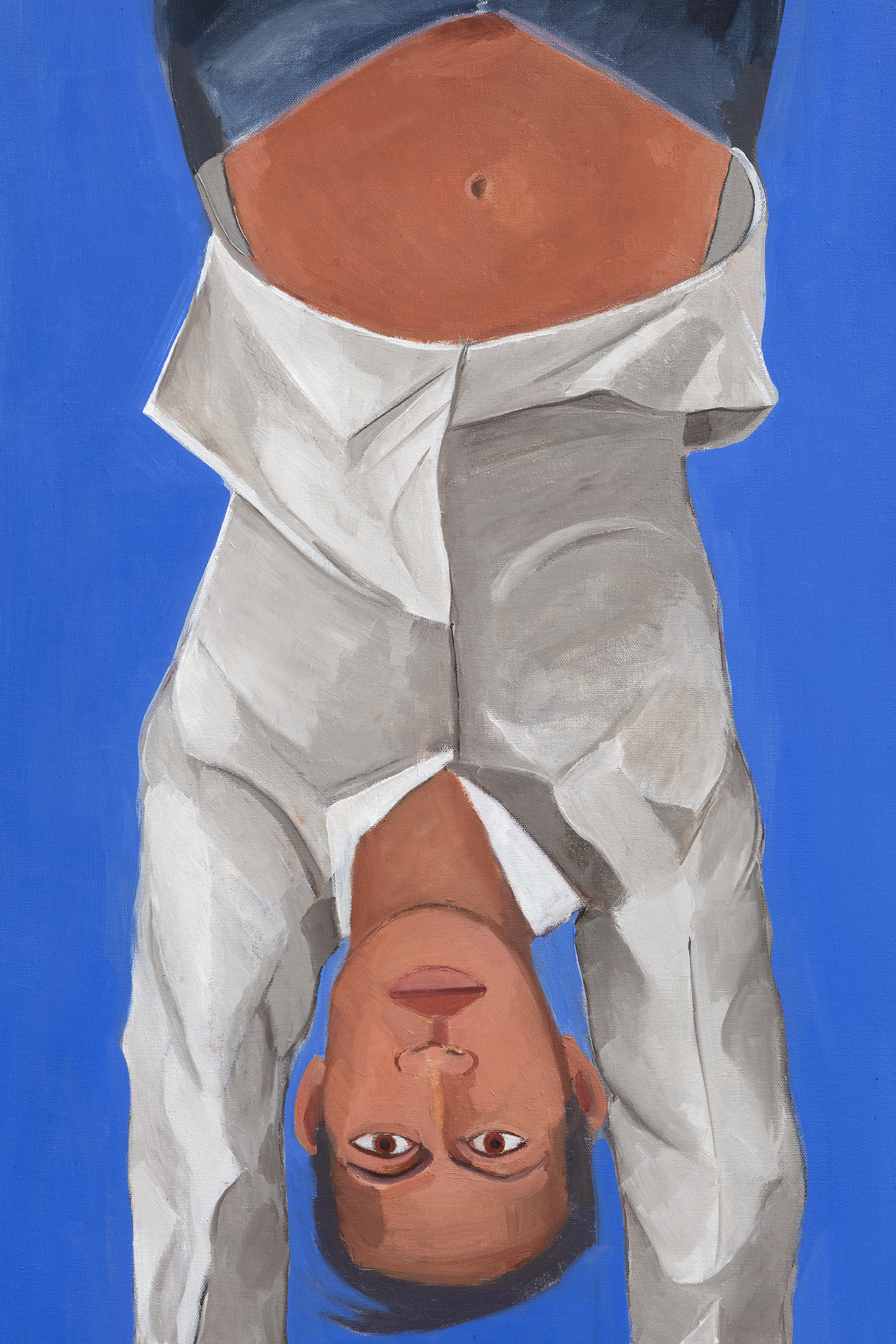

Roberto Gil de Montes, Untitled, 2021

SS: Your works on show in Venice, including El Pescador (2020) and Endangered Species (2021) among others, all masterfully queer, subvert and push the boundaries around familiar imagery (Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus) and the performative and dynamic possibilities of 2D works. Could you share more about your creative process for these works and how you think about their connection within the context of the curated show at Venice?

RG: All the paintings selected for Venice were conceived before I was selected, I didn’t know what the curatorial idea was until I saw the exhibit. I had done a small version of the pescador in 2005 while I lived in San Francisco, but it was not a pescador but a poet, I did another one 2010

and that was also a poet, when I decided to do the large version that is in Venice, I decided to change the poet to a fisherman. I finished it right before the beginning of Covid.

Roberto Gil de Montes, Untitled, 2020

SS: How do you think seeing your artwork in the context of the Venice Biennale changes or adds to the meaning behind the work?

RG: During Covid I was more isolated, less so than what was happening in the rest of the world but equally scary, people I knew died. From my studio in front of the town square I saw more funerals than usual. During this time I painted Endangered Species, fishermen, humans, tigers, and fish that are endangered. Three fishermen in a creek, one wearing a tiger mask, all facing extinction. One day I walked into my studio and saw a small painting of a human figure upside down on the floor, and I thought to make a painting with that idea, I used an old puppet as the model. When I finished it, I had the sensation that it was a very true reflection to what I was feeling. At first I did not see it as falling, but as hanging so I did another version thinking that I could make it hang, for that I had to paint a horizon, but I ended up painting it the same way. I wonder how they would look hanging together. The monk was another upside down figure, this one is floating in a body of water with drifting flowers. All the figures I painted upside down, like the monk, is not drowning, but it’s consuming itself as in a dream. Poets in the sea, is a little surreal. As I read about the ideas that Cecilia Alemany had for curating The Milk of Dreams, and the surrealist connection, I saw how I fitted in the exhibition. I could see why I was selected. I didn’t know that it was the first time in the history of the Biennale that a woman curated the exhibit and that it is the first time that there are more woman artists than men. I feel very honored to be included.

(Detail) Roberto Gil de Montes, Endangered Species, 2021

CREDITS

All images courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto

Click here to view the press release and to learn more about the artist.