Contemporary Female Identities in the Global South exhibition

The Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation’s inaugural exhibition contemplating the formulation and articulation of female identities

The following article was written by arts writer Christa Dee during the week on the exhibition’s public opening in September 2020. It was originally published on the South African-based publication Arts24. The exhibition was on show from 16 September 2020 – 30 January 2021.

Installation view including exhibition entrance. Photo Graham De Lacy.

Installation view including Bharti Kher, Warrior with cloak and shield (2008); and Wangechi Mutu, A Dragon Kiss Always Ends in Ashes (2007). Photo Graham De Lacy.

Contemporary Female Identities in the Global South is the first exhibition in a three-year curatorial programme with a thematic focus aimed at mapping out a generational genealogy of female identities within the Global South.

Each iteration establishes temporal layers surrounding an in-depth focus on female identities, told from the perspective of specific artists. The inaugural show includes artwork by Nandipha Mntambo (South Africa), Bharti Kher (India, UK), WangechiMutu (Kenya, USA), Shirin Neshat (Iran, USA) and Berni Searle (South Africa) from varying points in their careers. Tracing this lineage from the contemporary, the show initiates a narrative articulation guided by hybridity, as a lens for exploring identity construction and interrogation; an entry point established by the artworks present in the show.

JCAF executive director and curator Clive Kellner described how the immediate connection between Nandipha Mntambo’s mythological figures, Bharti Kher’s Self Portrait (2007) combined with Wangechi Mutu’s bronze sculpture Water Woman (2017) sparked the idea of hybridity as a conceptual and formal thread.

JCAF executive director and curator Clive Kellner described how the immediate connection between Nandipha Mntambo’s mythological figures, Bharti Kher’s Self Portrait (2007) combined with Wangechi Mutu’s bronze sculpture Water Woman (2017) sparked the idea of hybridity as a conceptual and formal thread.

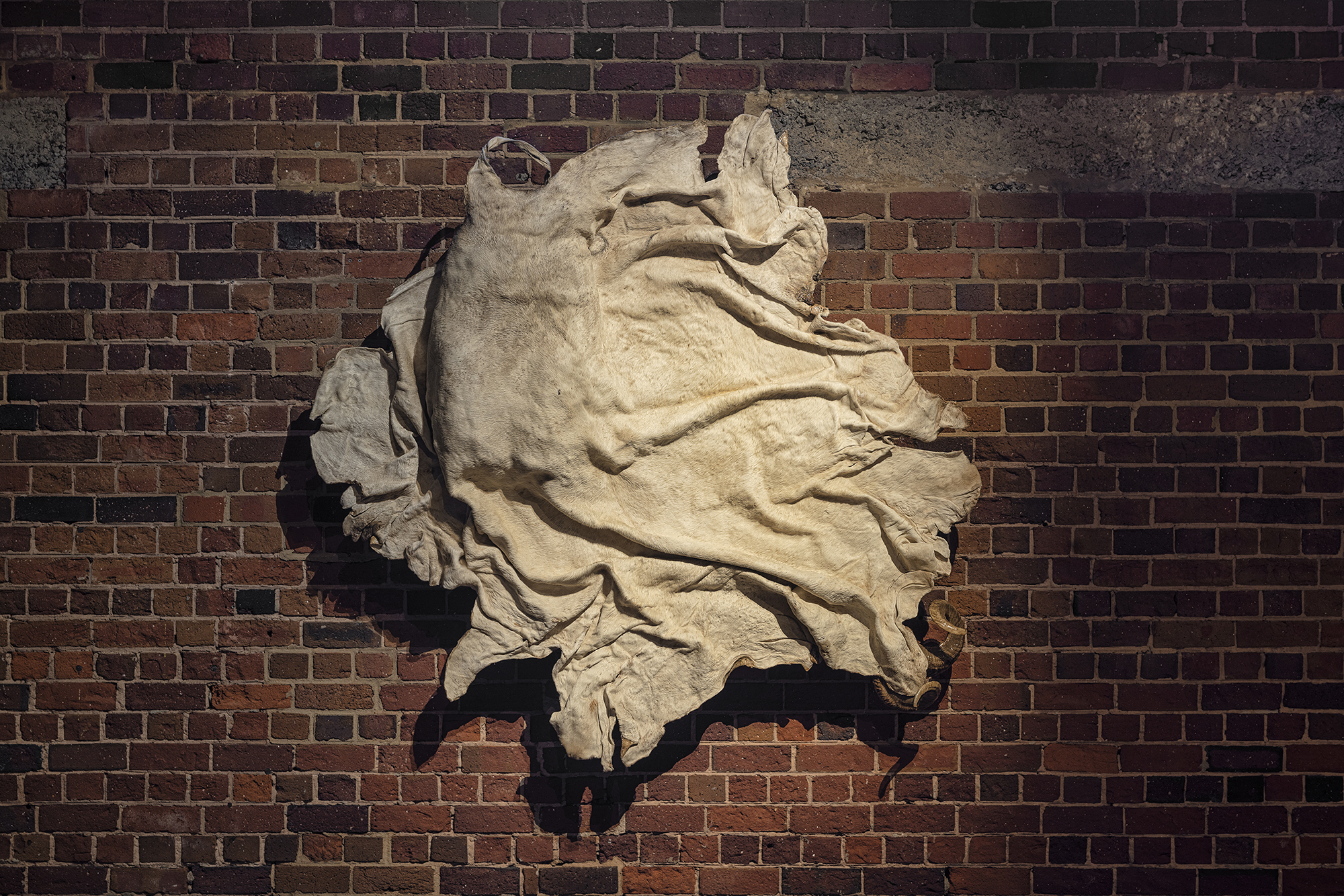

Installation view including Nandipha Mntambo, What Remains (2019); Bharti Kher, Warrior with cloak and shield (2008); and Wangechi Mutu, A Dragon Kiss Always Ends in Ashes (2007). Photo Graham De Lacy.

The exhibition can be viewed as existing in three sections or thematic worlds. Stepping into the exhibition space the viewer is greeted by Kher’s Warrior with Cloak and Shield (2008), a life-size figure of a woman, a guard to the entrance of this celestial and natural world.

Large antlers grow from her head, their grandeur and branch-like extensions exaggerated by the deliberately angled soft lighting from above. Curving towards her hands, she grasps them like weapons. Her shield, a banana leaf, is a disorienting notion. Seemingly inadequate for defense against physical intrusions, here it represents a set of metaphysical protection in Hindu tradition. The otherworldly and the physical are balanced by the hanging of an old work shirt on the left horn as a cloak and the Mary Jane shoes on the feet of the figure.

Kher’s warrior is present in the same space as Mutu’s collage A Dragon Kiss Always Ends in Ashes (2007). The female figure in the work is lying down, a stance often suggestive of passivity. However, the narrative present in the work subverts this assumption. She is depicted kissing a serpent of her own making, a move that cuts through the insistence that women occupy the position of the virtuous, the well-behaved and the submissive.

The figure becomes a representation of women as bold, able to create life and a relationship to nature that fits their desires for themselves. Two blinds are left open deliberately, the only source of natural light in the space. The green wall where this work is mounted and the shades of green, yellow and orange on the serpent’s scales is mirrored in the trees visible through the open blinds, inviting the viewer to connect the elements of nature outside to what exists in the works.

Mntambo’s What Remains (2019) hovers beneath the open blinds. A cowhide sculpture molded on the artist’s body suggests a human figure beneath it. Like her other work in this medium, there is conscious play between the female subject and what is seen and unseen, as well as the relationship between the human and animal. The ghostly feeling of this work, heightened by imagined movement of the hide, suggestive in its dance across the absent figure, points to the significance of contemplations on loss. Read in connection with the other works it directs one to think about the unrecognised work by women, warriors of the everyday.

Strategically constructed raised decks assist in the division of space, allowing the movement of viewers to mirror the layering of meaning. They also operate as transitional islands demarcating the different worlds created in the show.

Installation view including Nandipha Mntambo, What Remains (2019). Photo Graham De Lacy.

Strategically constructed raised decks assist in

the division of space, allowing the movement of viewers

to mirror the layering of meaning.

They also operate as transitional islands

demarcating the different worlds

created in the show.

Moving toward the second section, the underworld, viewers are presented with the works that initiated the conceptual framing for the show, along with Mntambo’s Sengifikile (2009). This bronze work takes on a rebellious energy with the horned female figure refusing to meet the gaze of the viewer, taking ownership of the act of looking and being looked at.

Mntambo reworks ancient European mythology in Europa (2008) by placing herself within the central narrative exposing the way in which European history is constructed through silencing and violence. In this work the female figure with horns and fur lives as a manifestation of dual forms – human and animal; hunter and hunted; defiance and seduction.

Kher’s Self Portrait (2007) uses the idea of the hybrid to engage with a similar theme. She contemplates the parallels between how society relates to animals and marginalised people who are considered ‘different’ or ‘other’. Her face is overlaid with that of a baboon, purposefully locking eyes with viewers in a similar manner to the figure in Europa.

Mutu’s Water Woman (2017) lies in the centre of this world. Half woman, half sea creature, this figure references both the dugong, an endangered relative of the manatee found in the waters from East Africa to Australia, and the East African folklore legend of the half woman, half sea creature (nguva in Swahili) who entices and eludes travelers.

Installation view including Wangechi Mutu, Water Woman (2017). Photo Graham De Lacy.

The third and final world is symbolic of the real world. Beari Searle’s Snow White (2001), a two-channel projection, sees the artist sit as flour and water pour over her body. In this work, the flour speaks to the institutionalised discriminatory classification system of apartheid where skin was assigned identifications of otherness. Being covered in white flour also symbolises the attempted erasure of indigenous and non-white cultural groupings in South Africa, pulling threads from Europa and Self Portrait into this third section.

Searle’s figure begins to work through the flour and water, forming a dough, the pat-pat sounds of this action creating a rhythmic sonic pattern heard across the exhibition space. This molding of the dough speaks to the agency of the figure in trying to formulate and resolve the parameters, hurt and distortion surrounding personal and national identity in South Africa. Searle’s figure covered in white flour is mirrored by Kher’s sculpture Mother (2016), a life-size plaster cast of her mother. The polished white surface of the work points to a European tradition of idealised marble constructions. The cast, however, captures each fold and wrinkle undoing the postulation of sculptural perfection and beauty through white, smooth surfaces highlighting Kher’s reflections on the skin as the body’s purveyor of memory. Here, the aging female body is on a pedestal in a pose that suggests self-contemplation, blocking the gaze and the descriptors projected on the female form.

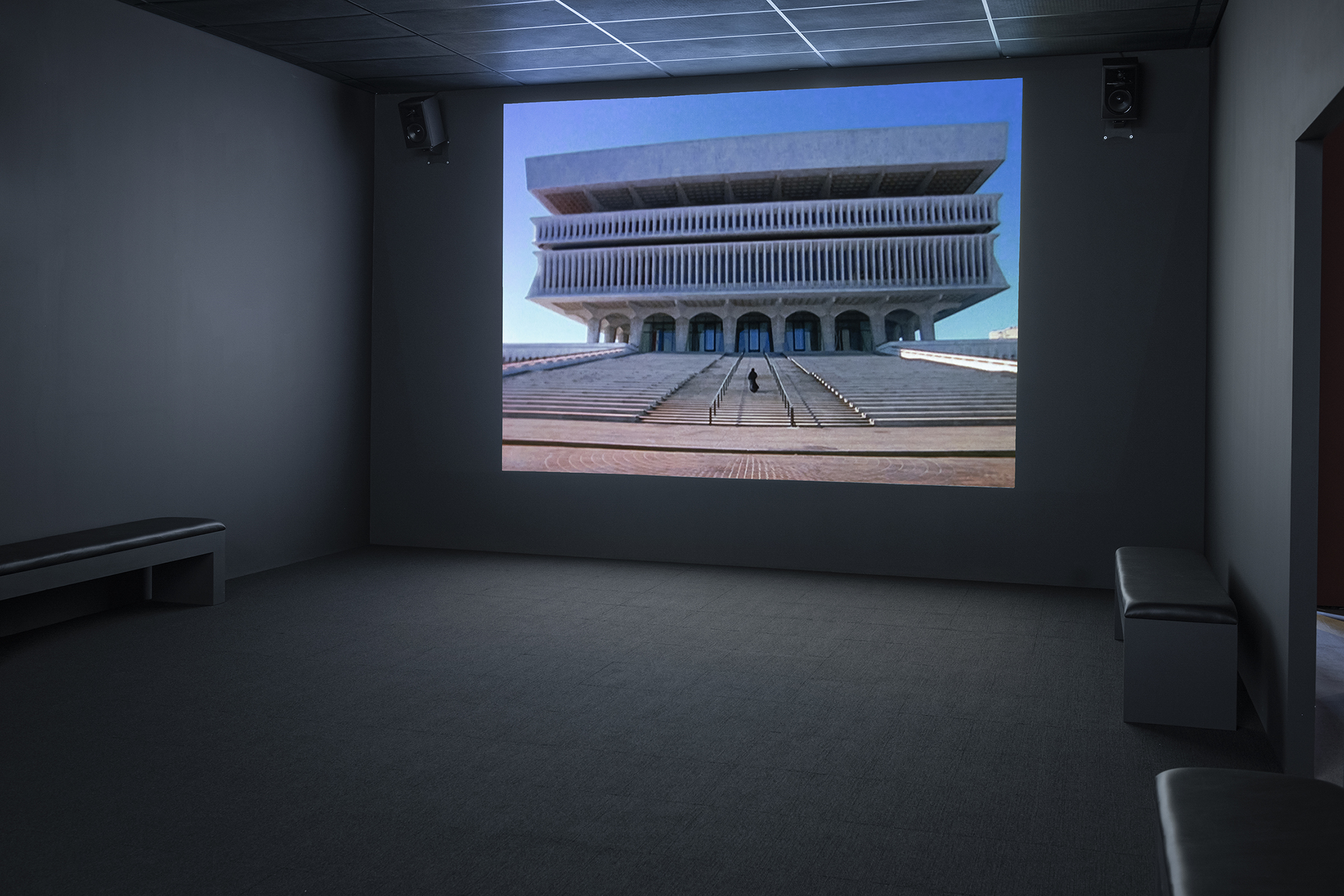

Searle’s onomatopoeic soundscape mixes with the hymns heard in Neshat’s Soliloquy (1999), producing an unintentional hybrid. This moment of exhibitionary hybridity elevates the hybrid identities of the artists themselves. Shirin, Wangechi and Bharti share the potency of a double identity of living in or having lived in the geo-imaginative North while having cultural, familial and epistemological roots in the Global South. This is particularly apparent in Soliloquy where the viewer, similar to Snow White, is caught between to projections. The narratives unfolding on either side share different places – a Middle Eastern palace and a modernist white building, among others. Neshat appears as the same veiled woman in both projections, alternating between being observed and observing, being part of a crowd and appearing in isolation. The woman is never able to meet herself across these projections but at certain moments is able to watch her other half, alluding to the strain and tension inherent in exilic identities.

Installation view including Bharti Kher, Mother (2016); and Berni Searle, Snow White (2001). Photo Graham De Lacy.

There is a hybrid relationship between the works, with the viewer’s position in the exhibition space determining what is visible and which works are within eye line. This fluidity layers the interpretation of work, pulling in different directions the thematic thread of female identities. Collectively there is a defiance against the expectations around the presentation of the female form, role of women, how identities are exercised in everyday life and across one’s life journey. The female figure is seen as aging and beautiful; martyr and dangerous; solitary and part of a collective; veiled and naked; and always taking ownership of her own form and relationship to the world.

Installation view including Shirin Neshat, Soliloquy (1999). Photo Graham De Lacy.