An interview with Gor Soudan

An artist whose work has developed through travel, exploration of materials and care

Gor Soudan is a conceptual artist living and working in Kisumu and Nairobi. Often subtly engaged with contemporary political and social issues and embedded in urban culture, Gor’s artistic practice is an organic process through which everyday material is transformed into powerful work. He has worked with pages of the Kenyan constitution, carton, plastic, shopping bags and ‘protest wire’ – a tangled black mass of wire he salvaged from car tyres burnt during civil unrests in Nairobi brought about by political tension.

His practice and the works he produces provide acute, often satirical observations and comment on the rapid socio-political transformation Africa, and Kenya in particular, is undergoing. SOUTH SOUTH interviewed the artist to find out more about his practice.

Gor Soudan, Observatory-Epiphany In The Grass III, 2022

Acrylic Ink on watercolour paper

152 x 124cm

Gor Soudan, Observatory-Epiphany In The Grass II, 2022

Acrylic Ink on watercolour paper

152 x 117.5cm

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): For our readers from across different regions who may be being introduced to your work for the first time, how would you describe your approach to art making?

Gor Soudan (GS): I am subconsciously leaving marks on this fleeting temporal experience, weaving a pattern in my mind’s eye, not knowing where I am coming from nor where I am going. I ground my experiences in silent materiality, creating synaptic objects for educating my conscious self to conceive its latent awareness of infinite creativity as a quantitative force.

My approach is often formal or process driven, however, there are also numerous instances where my approach is concept-driven, particularly within my sculpture, installations as well as my interactive and collaborative work. My attitude towards media is an open and intuitive process. The concept is important. The media is vital in communicating the concept.

My foundation was at Kuona Trust Centre for Visual Arts, Nairobi, where I was able to interact with, learn from and share experiences not only with my peers but also with established art professionals, local and international, such as Peterson Kamwathi, Cyrus Kabiru, Kaloki Nyamai, Jackie Karuti, Ntando Cele (SA) and many more. Peer-to-peer learning through workshops and presentations/talks was the means of acquiring skills and knowledge, even as the world wide web was enabling us in Nairobi to get into the information superhighway and knowledge networks.

In Nairobi from 2008 to 2013, the mood in visual artists’ circles was particularly sensitive to prevailing politics and current affairs. We were somehow a fringe community, unseen and unheard, except by an exclusive elite clientele largely constituted by an expatriate class. We, the young artists, were urban cyclists. A motley bike ‘gang’, as documented in the exhibition The Bike gang by artist John Kamicha and researcher Sam Hopkins in his video about Nairobi biking culture presented at Goethe Institute in 2017. We tended to have very strong ideas and opinions, particularly on art and its purpose. Art was about protest and articulating our positions on socio-political issues, with themes revolving around identity and inequality.

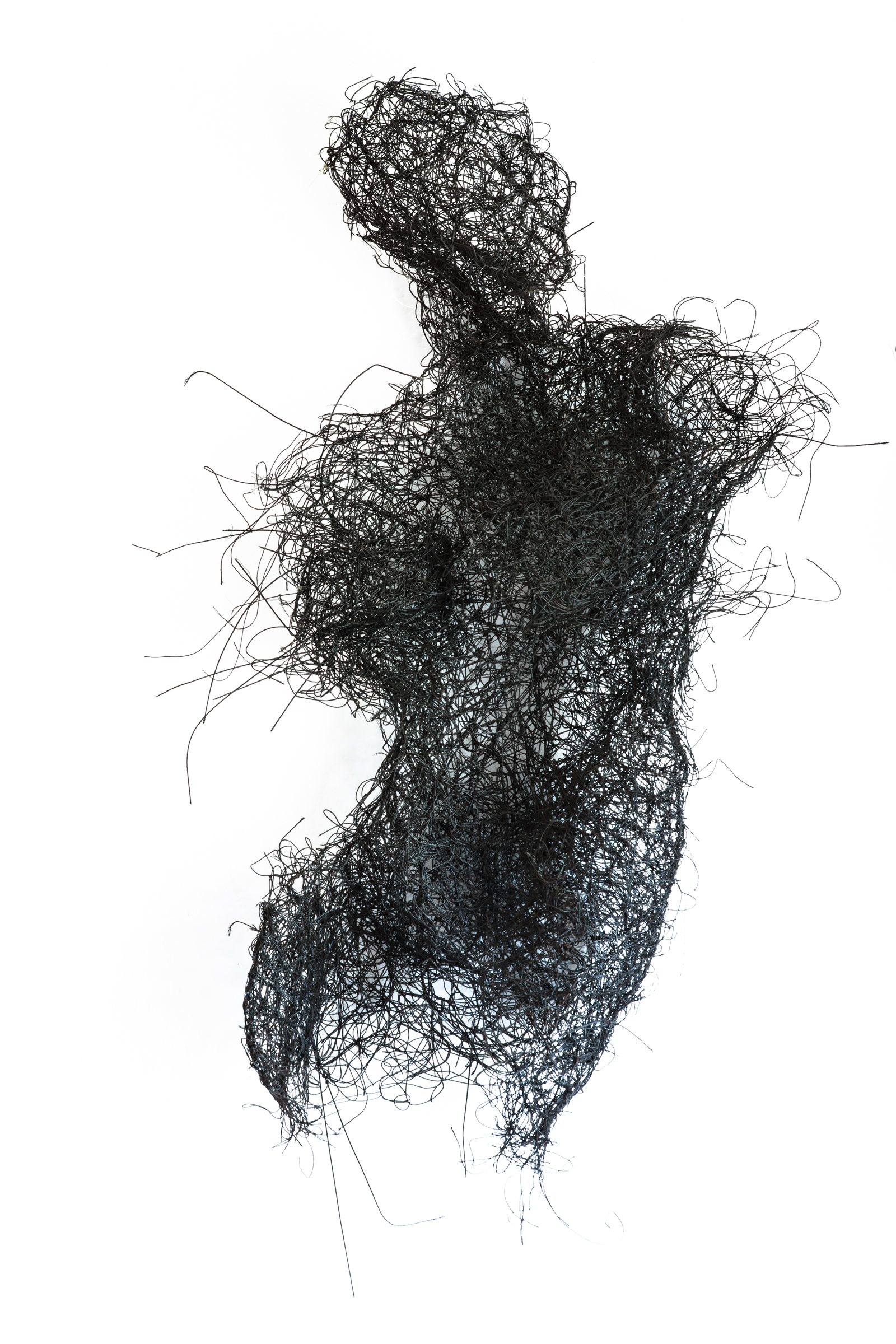

Installation view

Gor Soudan, Bubbles & Shells IV & V, 2014

Wire

Photograph courtesy @ARTLabAfrica

My attitude towards media is an open and intuitive process. The concept is important. The media is vital in communicating the concept.

I was traversing different social bubbles of Nairobi, from Kibera to Karen on my bicycle, witnessing Nairobi’s glaring social fault lines amid rapid economic growth. Travelling out of the country for an extended period in 2014 to West Africa and Japan was a time to experience foreign cultures and geography. Every single day was an adventure; new languages, food, places, art, architecture and people. This had a tremendous impact on my conception of the world and my approach to art making. Experiencing cultural relativism firsthand, first in Freetown, living in Aberdeen where you could still find colourful Krio ‘bode ose’ (board house). These were reconstructions of American cabins of the 18th century, pointing to Salone’s historical connection to America, and hence Africa to America via the transatlantic slave trade.

My partner had found work in the country working for the NGO Save the Children, so I went along. I claimed the backyard of our house in Aberdeen as my studio. I acquired a bicycle and became friends with the dealer who, other than importing used bicycles from the USA, also ran a bike mechanic shop on Pademba Road across town, past the huge Iconic Cotton tree on Siaka Stephen avenue.

I scavenged discarded and abandoned objects and materials such as used bicycle braking and gear steel cables which I wove into geometric sculptures back at my studio in Aberdeen. Some evenings I took djembe drumming classes at Lumley Beach roundabout with Abdul, The Drummer. Sometimes the drumming sessions took place at Lumley Artist’s village which housed Abdul and other musicians, acrobats, fire eaters, dancers and other performers. The housing was provided for free by the state.

Apart from the cable sculptures, I was finishing small ink studies on paper. My subject was geometric forms I could see within the weave of my sculptural works and the shadows they cast on surfaces. These drawings, therefore, took entangled and sometimes organic forms in different stages of growing or developing into a more complex form.

Towards the end of my stay in Salone I prepared a pop-up exhibition, Always fen fen some tin (Always searching for something). It included installation sculptures and ink drawings. I presented the work created during my stay to a cosy gathering from the expatriate community and Freetown residents.

Whilst still in Freetown I received news of acceptance into The Backer’s Foundation Fellowship and Artist In Residency program at Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT); an incredible 3-month opportunity to live, work and show in Tokyo. In the meantime, in Salone, an Ebola virus outbreak (2014) was just beginning to spread from the border with Benin but had not yet reached the capital, making my departure from Freetown a bittersweet experience.

Installation View

Gor Soudan, Bubbles & Shells V, 2014

Wire

75 x 35cm

Photograph courtesy @ARTLabAFrica

I had a brief stay in Nairobi during which I also managed to work on a small series of sculptures titled Bubbles. These were small, spherical sculptures made from ‘protest wire’ which I brought out of storage. I was also processing my experiences and connections from the time spent in West Africa where the viral outbreak had eventually broken into a full-fledged epidemic threatening the whole global population’s health.

I arrived in Tokyo in May 2014, to an urban experience like no other. My residence was in Ochanomizu suburb near Ueno where I developed a habit of taking long exploratory excursions in the city, visiting public gardens, museums, window shopping in Harajuku and shopping for veggies at Ameyokocho, once a thriving black market during the American occupation of Post World War II Tokyo.

My interest in ink drawing peaked here, perhaps due to exposure to Japan’s long uninterrupted art history, access to and availability of incredible media such as inks, brushes and handmade paper which were like art in themselves. I admired the cultural attitude and appreciation of art making, the attention to detail, to process, the push and pull of form and formlessness and honouring of the part as well as the whole in equal measure.

My sculptural installation at the two-man exhibition, Albert Samreth and Gor Soudan (2014) at Yamamoto Gendai Gallery, which was held at the end of the residency was conceived as a space on the floor, by a flat circular woven mat woven out of igusa (Japanese rushes or long grass), on which one was invited to sit and retrieve, for closer examination of the woven form, a smaller circular sculpture cut from the big one.

In Lamu Island, on the Kenyan coast, I became interested in the 17th-century Swahili Arab architecture which was fortunately conserved at the UNESCO world heritage site. I examined surfaces, such as the beautiful hand-carved doors, wall deco, patterns on furniture, and other cultural materials in my environment. Lifting different textures is done by rubbing graphite on paper against it, and then making tight ink marks along the revealed forms to reveal two-dimensional representations of these surfaces. These drawings were presented the following year, Imprints, 2016 ink drawings on Japanese washi.

Installation View

Gor Soudan, Eatings I & II, 2013

Photo courtesy @ARTLabAfrica

SS: Your work incorporates drawing, sculpture, installation and ceremony and often reflects social relationships and interactions with the immediate environment. Could you share more about your thematic interests and your connection to them?

GS: I channel my ideas as memories. Discovering new ideas and making decisions in art making often come as a memory, as if it was there all along, waiting to be acknowledged. In my studio, usually a small room, I often work alone. However, I have worked with a studio assistant on some projects – in one instance the assistant eventually turned collaborator in my art film Barking up the wrong tree, 2018 in which he is seen nailing small shoe tacks repeatedly into a dead plant root system while leaving as little space as possible to create an iron scaly skin over the dead root. The video employs different angles, zooming in and out, while the sound of the nailing stays rhythmic throughout the whole recording.

I also do collaborative projects, such as with artist Jackie Karuti to produce performance art Seer (2016), in which the performer, Karuti, wearing an overcoat, repeatedly pours hydrogenated cooking oil onto a cast steel frying pan on a jiko (charcoal stove) creating a mist of oil, whilst enclosed within a nylon net cover. At the same time, a video of clouds in slow procession is projected onto the performance. This production was part of a show with the environment as its them at Goethe Institute Auditorium. The work was examining gendered identity and roles within the framework of the conversation on environmental sustainability and conservation.

Gor Soudan, Eatings I, 2013

Diptych

Protest wire

Photograph courtesy @ARTLabAfrica

SS: During the early moments of your career you created installation sculptures, ‘The Fire Next Time’ in response to the 2007 civil conflicts in Kenya. What was the process for creating these works and how do you think they represented the way you were developing your practice?

GS: ‘Protest wire’ (name came via Abby Higgins, then a young writer, now working as a journalist with Washington Post) was the black, twisted wire left from burnt-out rubber tyres that had been lit to create infernos barricading roads all over the country during communal conflicts.

I mobilized a small crew to salvage and haul carts of ‘protest wire’ from Olympic bus stop, amidst political protests and demonstrations back to The Jolly Guys Social Club, as my studio was known. For the next 2 years or so, at my studio which had already moved from Kuona Trust Art Centre to Ayany Housing estate within Kibera (2011), I wove this found media until the time to part ways with it came in the form of an opportunity to travel, first to Freetown, Sierra Leone and on to Tokyo, Japan in 2014. I was glad to move on from protest wire and protest art to new artistic challenges. Loads of the protest wire was left over, which I kept in storage.

One of the recurrent themes in my work is the dichotomy of the Individual vs the Collective, or the part vs whole, the individual in the collective. My sculptures are created out of discrete parts that are put together to form a whole. They are organismic such as of individual cells that make up an organ, and organs working together to sustain the organism.

My process is formal, making decisions on how best to make use of media. I work the media until it conveys the concept or theme conceived. Even my ceremonial productions examine the form that the ceremony takes, while the material elements of the performance are used to convey the concept. Observation of the finished, or sometimes unfinished, artwork is critical because through this process the previous ideas may guide but not dictate the next.

I am interested in weaving and analysing through drawing with ink, the patterns and forms held within a woven surface. I can’t help perceiving this infinite woven form, aka the grid, in literally everything around me, and conceiving it in the nature of how ideas also flow through my mind. Connections and entanglements within and without.

Works from this duration worthy of mention are: Angry Birds (2012), a sculptural installation; Eatings I and II (2013), ‘protest’ wire sculptures; Fire Next Time (2013), a ‘protest’ wire sculpture installation series; and Bubbles (2014), protest wire sculptures. The Fire Next Time (2013) sculpture installation series is the moment when certain events, ideas and materials intersected and entangled. Bringing all this together through the weaving process resulted in a sculpture series which tries to examine the mythology and politics of intersectionality.

Gor Soudan, Eatings II, 2013

Diptych

Protest wire

Photograph courtesy @ARTLabAfrica

One of the recurrent themes in my work is the dichotomy between the Individual and the Collective, or the part vs whole, and thinking about the individual in the collective. My sculptures are created out of discrete parts that are put together to form a whole.

SS: How would you describe the evolution of your practice since the works mentioned above?

GS: Perhaps as a cyclical revolution, an unending process of observation and discovery, execution and examination of that which is revealed, the process always referring back to itself, resulting in an overarching pattern or rhythm, ebbing in and out, coming and going, zooming in and out, light, shadows, folding and unfolding.

My work is constantly evolving, formally, becoming more and more complex in outlook. Nonetheless, conceptually it is going through a constant introspective process where the overarching themes are analysed over and over: a process of distillation, through artistic research and practice to test their relevance and longevity. My intention, throughout, is to communicate my inner experiences in a clear simple visual language.

In my mind’s eye, I approach work with the same energy and intent; being honest and open to my media, allowing myself to enjoy their respective attributes so as to reveal the story underlying what the media means, what it does, and what it wants to become.

I have a keen interest in weaving as a process, and its resulting patterns. My work increasingly attempts to achieve these visual qualities. Conceptually, my themes still tend to track cultural intersection points but have moved away from socio-political commentary to thinking about our position, relation and roles within nature. I approach my subjects, whether in landscape drawings, botanical drawings, or woven sculptures with the precept that my environment is a vital, living and sentient force which can only reward my endeavours if I grant it the same level of respect as I would a sentient being.

My practice has adopted reciprocity as an approach. I seek to find the balance between creating works and artist projects which not only take inspiration and raw material from the natural environment but also seek to actively sustain the environment to achieve a sustainable art practice and art-making environment.

2018 and 2019, my studio was based within a nature conservancy, Silole Sanctuary, next to Nairobi National Park. It was the perfect studio, overlooking the park, the only separation being a river. No fence exists between the park and the sanctuary, and the animals move freely between the two. It was an experience which tuned my natural love for nature and made me aware of just how interconnected and interdependent we, the biosphere family, are within the whole natural world. Watching scarab beetles tirelessly mopping up huge buffalo dung can offer a refreshing perspective on the who is who in nature.

During this period, I mostly finished ink drawings on washi, examining the natural forms in the bush. How individual leaves each takes up their own space on a branch, careful not to overshadow the neighbours, all of them stretching out to capture the sunlight needed for photosynthesis, and unintentionally leading to the eventual form that the whole plant’s leaf system takes. The acacia tree has a flat top so that the tiny leaves are all exposed to the sunlight, giving it its unique form. I was able to notice that natural patterns within nature are a result of nature’s intention. The purpose inspires the design, within nature.

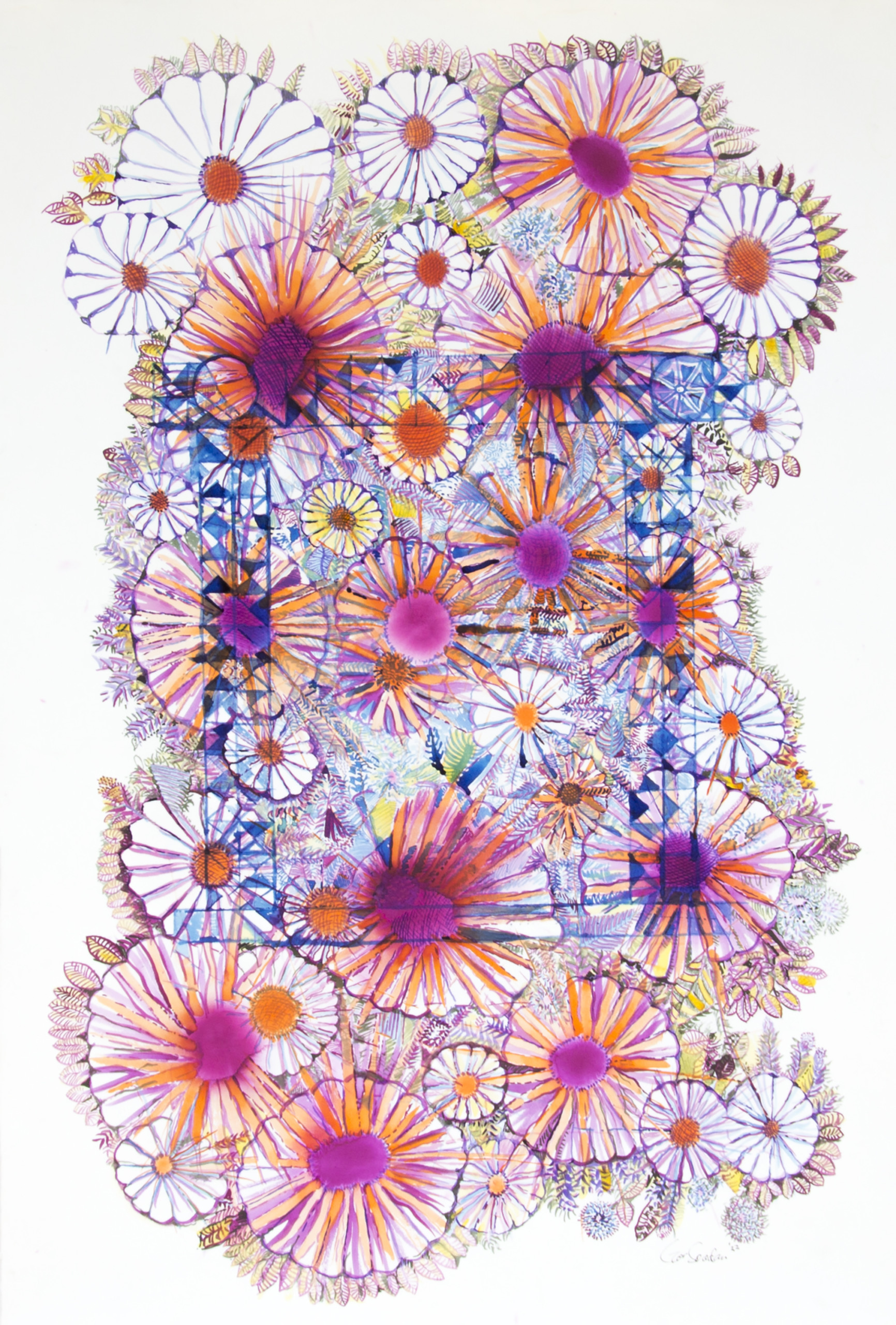

Gor Soudan, Where Do Flowers Come From III, 2022

Acrylic ink and coloured ink on watercolour paper

113 x 76.5cm

My work is constantly evolving, formally, becoming more and more complex in outlook. Nonetheless, conceptually it is going through a constant introspective process where the overarching themes are analysed over and over: a process of distillation, through artistic research and practice to test their relevance and longevity.

SS: You co-founded a communal art space embedded in a market garden and tree nursery, which will act as a centre for art within an agroforestry project. Why do you think it was important to create this space within the area that it is situated? How do you envision the long-term life for this space?

GS: Eventually I returned to my hometown Kisumu in 2019. I was mentally exhausted, in need of a break from the capital’s hustle and bustle. I was estranged from my family, with my daughter residing on another continent with her mother. I was drinking too much, smoking too much, and barely eating.

My plan had been a tactical retreat before eventually jumping back into the fray of the Nairobi art scene. However, the following year, there was another viral outbreak – this time it wasn’t Ebola in Africa, but Coronavirus in China. The resulting period of lockdown meant that I was stuck in the village, which actually turned out to be a good thing in the end.

While living in the village, I continued to study my environment – which consisted of smallholder farms growing maize, cassava and plantains. People also rear animals for domestic consumption and as a means of saving money. I rediscovered the joy of gardening during the day, nurturing plants, and growing trees in my mother’s compound. I also rediscovered the frustration of slashing grass and the unending physical endurance where the grass seems to grow continuously.

I became focused on visually researching farming solutions and traditional technologies and the unintended aesthetics of their materiality. These interventions have their own aesthetic. A traditional homestead and garden have their own old appeal. Locally made tools look almost ancient in design. Ox ploughs fabricated by the blacksmiths at Holo Market, cattle are branded with designs to communicate ownership, and fencing with different plants and materials. With maize, planting is done in a gridlike formation so that the optics of the land evolves from a grid of planting holes to a grid of fresh soil mounds. Then, as the maize begins to germinate, a grid marked by emerald seedlings, and so on as the plants develop until harvest time when the tall green stalks turn golden in the summer sun.

Harvest is done around this time when the cobs are plucked from the plants, which are then bent in the middle so that the crown is pointing downwards. Coming upon a harvested field, the drying and broken corn are exhausted and dying from the labour of bringing forth the next generation.

Gor Soudan, Where Do Flowers Come From I, 2022

Ink on watercolour paper

65.5 x 77.4cm

The cobs are ferried back to the home, by every individual in the household and in most cases, neighbours come to help. It’s a communal effort, labour is compensated by a good meal and milk tea, and the more sugar the better. They use handwoven baskets made from locally grown plants, olando. The baskets, skilfully woven, are sometimes battered in exchange for maize.

My somewhat idyllic view of village life should not hide that this is also a place with a lot of needs. It appears to be on a collision path with the urban cities I have had the privilege to visit. I am an odd character in the village, with an odd profession. Oftentimes, I felt misunderstood. My kind and I are referred to as ‘the ones lost outside’, people who went to the city and adopted the urban culture.

I wanted to communicate my experience here in the village, but my vocabulary betrays me. So partnered with one weaver, he would teach me how to weave and together we would weave baskets and other handicrafts and art too. A third weaver joined us. We had a small collective going on.

It was a great experience, exploring the countryside, looking for olando on the rocky bushes of the Seme Hills, bordering the lake to the west. The whole experience of my apprenticeship with the weaver made me think of working in a studio where this kind of experience is encouraged and instigated. It is not just an experience of skill sharing, but a place where I could finally, in dialogue, articulate my experiences as an artist in the appropriate setting and audience.

The communal art space, as an observatory embedded in a market garden and tree nursery, has been conceived as a sustainable project due to its garden produce sales, and the tranquil hills and clean environment are perfect for art making and will hopefully, in the long run, attract artists who seek this kind of dynamic in their practice.

Gor Soudan, Where Do Flowers Come From II, 2022

Acrylic ink and coloured ink on watercolour paper

113.5 x 75.5cm

The communal art space, as an observatory embedded in a market garden and tree nursery, has been conceived as a sustainable project. This is due to its garden produce sales. The tranquil hills and clean environment are perfect for art-making and will hopefully, in the long run, attract artists who seek this kind of dynamic in their practice.

SS: You showed a new body of ink drawings with Circle Art Gallery at 1-54 this year. These are works that have never been shown in London before and are part of a woven sculpture and installation project initiated in 2019, entitled Observatory. Could you share more details about the work and how they connect to your current research?

GS: Whilst living at Silole Sanctuary, I really rediscovered my unbroken bond with nature, vegetation and wildlife. I started incorporating forms analyzed from nature by mark-making. Epiphany in the Grass, coloured ink drawings on paper, form part of a larger ongoing work with woven sculptures and installation which has slowly been building up during my two years in the village since. The drawings began to take shape as small landscape studies which I made, sometimes as maps of the geography of my walking paths, or as landscape scenes observed during strolls.

On return to post-lockdown Nairobi, I had the urge to work on these large drawings, which analyze natural botanical patterns, art and craft forms and icons found in my physical and sometimes virtual environment: architecture, arts, crafts and symbols. I rely on my first-hand experiential exploration from places I have travelled to (Kisumu, Lamu, Lagos, Tokyo and Sierra Leone) analyzing my internal mental landscape in an attempt to make sense of my space and time. Some of these patterns and symbols, e.g. Lamu door patterns, Ethiopian traditional crosses, emojis, signs and even particular hues of colours are superimposed within the natural flora and fauna forms studied during the ongoing agro-forestry project. This particular work attempts to provoke a sense of our micro and macro awareness of the present condition of our world, the sense of working in a rural market garden environment, whilst also being part of a global artistic community. Moreover, the drawing also alludes to ideas that our conception of the ‘glocal’ (local and global) environment as being the foundation of our internal concept of language, spirituality and science. These drawings, at this point, may be considered as only the latest instalment; an update of a long and meandering visual research project since I first started leaving marks.

Gor Soudan, Observatory-Epiphany In The Grass VI, 2022

Acrylic Ink on watercolour paper

152 x 141cm