An interview with Theresa Musoke

An exploration of an ever-evolving practice

Theresa Musoke is one of Uganda and East Africa’s foremost artists. Musoke considers herself a semi-abstract painter and is best known for her expressive portrayals of the region’s abundant wildlife, using a range of mediums to develop her imagery. Musoke’s paintings are suggestive rather than realistic, merging the forms, colours and movements of animals with their environments. Her technique involves with dying her cotton canvases randomly, first, and then painting on them. The dye stains suggest forms on which she works with acrylic and oil paints until they resolve into a unified composition.

Musoke’s first began to receive attention while she was an undergraduate student at the Margaret Trowell School of Fine Arts at Makerere University in Kampala, where she won the Margaret Trowell Painting Prize in 1965 and received a solo show at the Uganda Museum. After she received her BA, Musoke worked for some time as an art teacher before receiving a scholarship to study for a postgraduate diploma in printmaking the Royal College of Art in London. Following this, she went on to complete and MFA at the University of Pennsylvania.

Musoke has been a highly influential figure in Kenyan and Ugandan art, not only for her celebrated visual practice, but also as a teacher. After completing her studies, Musoke returned to live in East Africa, living first in Kampala where she taught and Makerere University, before relocating to Kenya in 1976. She lived in Kenya for over 20 years and taught at different institutions including the University of Nairobi, Kenyatta University, the International School of Kenya, and Kestrel Manor School. Throughout all this, she exhibited frequently in local galleries such as Paa Ya Paa, Gallery Watatu and the African Heritage House. She was also active in Nairobi’s art scene and facilitated numerous informal workshops to help young artists to develop new technical skills.

SOUTH SOUTH interviewed Musoke to find out more about her practice.

Theresa Musoke, Wildebeest (in blue and black), 1992

Oil on canvas

81x101cm

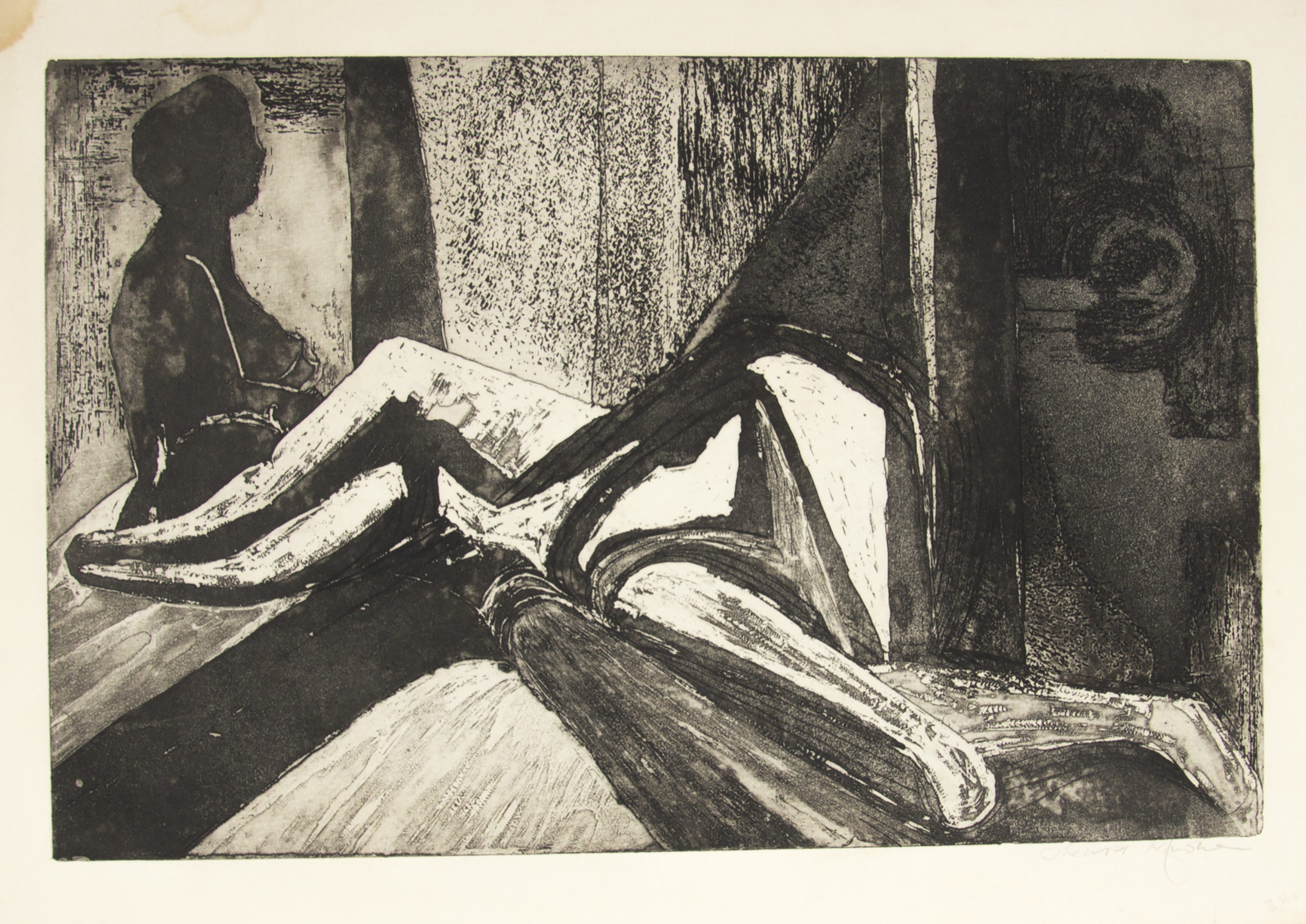

Theresa Musoke, Untitled (Woman), Undated

Monoprint on paper

32.5×50.2cm

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): For our readers from across different regions who may be being introduced to your work for the first time, how would you describe your approach to art making? How would you describe the evolution of your practice?

Theresa Musoke (TM): The subject matter of my paintings tends more or less to determine what colours I use. That being said, once I put down the first brush stroke, new suggestions form and new ideas come, and I allow myself to be guided by these strokes and ideas. I am never conformed to a certain palette or color scheme, the colors evolve as I go along, it is a continuous process. I normally use canvas and paper, but now I am experimenting with mixed media. Once I have my paint – and if I don’t have a particular kind of paint that I want, I then tend to figure out what pigment from organic things can work on the canvas and create my own – then I go from there.

My practice has changed a lot over the years. The subject matter for example, when I was at Makerere University – we were all students, so I didn’t have many resources or chances to go and look for the subject matter, I painted wildlife mostly and people. I don’t paint on the spot, so what happens is once I have an idea of what to paint, I either go for it, or find a resource to work from. Then I go stroll around, put it to the side and I start again, and it goes on and on like that.

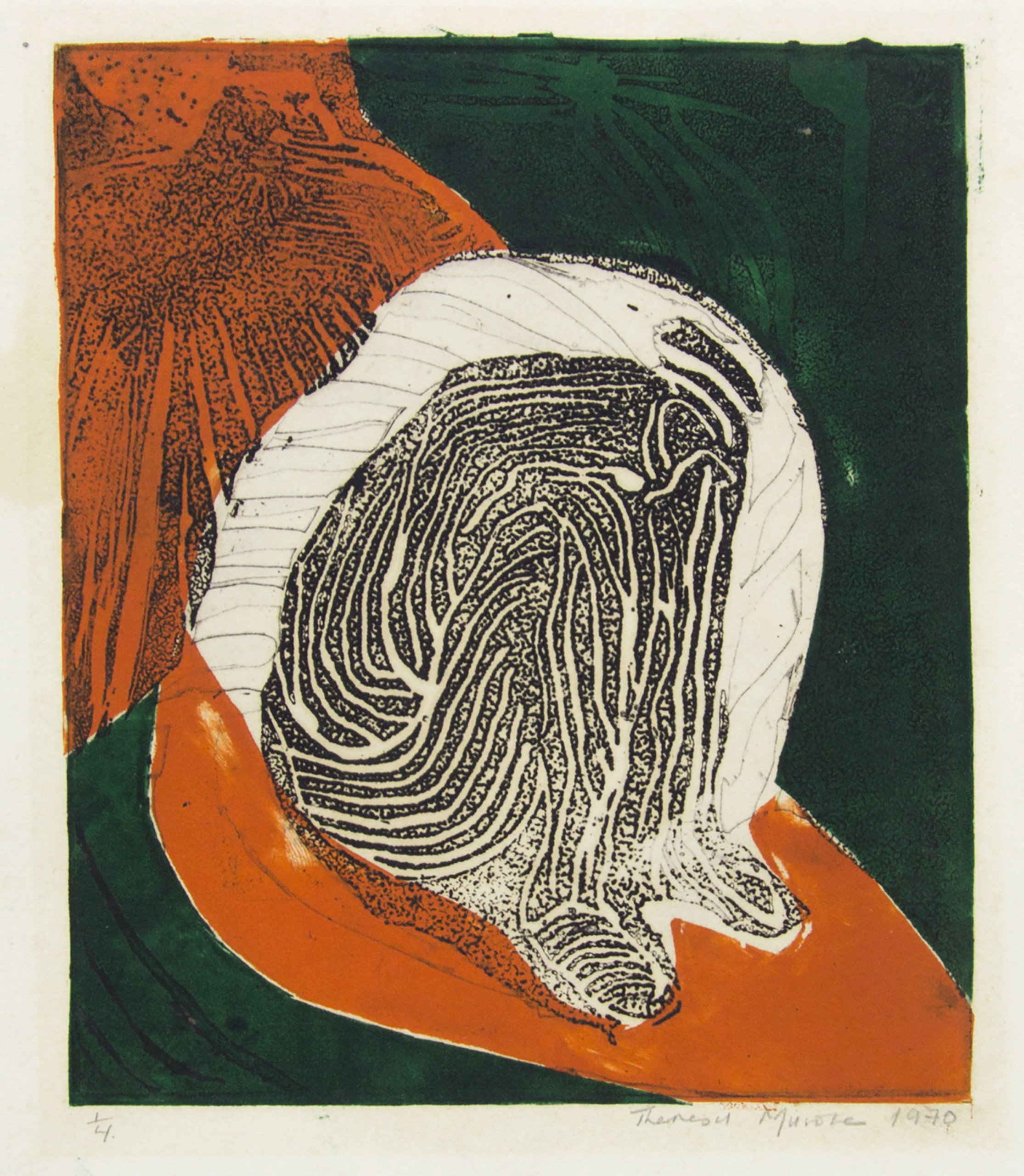

Theresa Musoke, Untitled IV (Seated Figure), 1970

Monoprint on paper

20.3x17cm

The subject matter of my paintings tends more or less to determine what colours I use. That being said, once I put down the first brush stroke, new suggestions form and new ideas come, and I allow myself to be guided by these strokes and ideas.

SS: You are best known for your semi-abstract portrayals of East African wildlife. Where does the connection to your subject matter come from?

TM: The interest in wildlife came when I moved to Kenya. I had plenty of time to go to the Masai Mara and other game parks. Wildlife allowed my art to evolve. Once you have seen the animal for the first time, they never look the same the second time around. I became very fascinated by the energy that holds everything together and I realized that everything is connected. So, you can be painting wildlife and then you see similarities in the plants, and you wonder how a man can turn into a giraffe, the whole thing grows from the ground up. If you come across a sunset, it almost becomes magical. Things are melting into each other and moving all the time. That type of energy fascinates me. The other thing that is interesting is time. Some things are timely. I also realized that if you want to tell a story or say something you don’t have to paint people. It is fascinating for me. Mind you, I haven’t solved it. Each time I take a new painting, I start seeing new and different things, thinking about what holds this together or what does that mean. East African landscapes are very vibrant. If you go to look at something and you stand there for a long time, you find out what you thought at first changes; it changes with the mood, it changes with the feeling. There is no particular formula. The only thing that determines a painting is time.

My favourite animal to paint is a giraffe. I like giraffes and I like animals because they don’t talk back. And the landscapes, with the mix of the plants the colours and the shapes, they recreate themselves over and over again. Every time you go to look outside it’s different. Everything you put down seems to have its own power to drive you.

Theresa Musoke, Wild Dogs I (Yellow), 1990s

Mixed media on canvas

77x104cm

The landscapes, with the mix of the plants the colours and the shapes, they recreate themselves over and over again. Every time you go to look outside it’s different. Everything you put down seems to have its own power to drive you.

SS: How do you think about the audience for your work? Does this influence your thematic references or the ways in which you present your work?

TM: The audience doesn’t come into it initially, but since everybody is human, inevitably the audience is a factor. If I feel strongly about something, there must be someone else in the universe that feels strongly about the same thing. People lean to paintings like an experience, someone somewhere is going to fall in love with it, but because I don’t know where they live or who they are, I don’t think about the audience.

Theresa Musoke, Hartebeest (In Blue and Pink), 1995

Oil on canvas

116x78cm

SS: Your work was selected to show alongside six other East African contemporary artists as part of Michael Armitage’s Paradise Edict which launched in Haus Der Kunst in 2020 and moved to the Royal Academy of Arts. Could you share details about the work on show? How do you think seeing your work in these two contexts changes or adds to the meaning behind the works?

TM: The lithograph, yes, I did that in the 70s. It’s a landscape from the very first time I visited Kidepo National Park. The first time I went there, the sky and the animals seemed to be one, depending on the time of the day the shapes seemed to appear and disappear which was exciting for me. From there I went to other parks in Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, with a friend and I was just fascinated by the beauty of those places.

All my paintings were not bought by people that are local inhabitants, in terms of galleries. Yes, Paradise Edict has gained me recognition, but in terms of sales, I have always had an international audience. A lot of my work is not in Africa. The show is important because it is re-introducing an African audience to my work. Ugandan people don’t know my name. They do hear a bit more about me, but the exhibition brings the attention back to an African audience which is a really nice thing.

Theresa Musoke, Untitled (98),1996

Mixed media on canvas

147x99cm

The show [Paradise Edict] is important because it is re-introducing an African audience to my work.

SS: You were included in Circle Art Gallery’s East African Masters at Cromwell Place in London showing a selection of oil paintings (Hartebeest in browns and purple [1999]; Hartebeest (in blues and pink) [Undated]; Egrets in blue [Undated]; Wildebeest (in blue and black) [Undated]; Wild Dogs I (Yellow) [c. 1990s]). Could you share more about the process and inspiration for creating these works? How do these works fit into the way you thought about your practice at the time of making them?

TM: As I say, I use mixed media, which is confusing. You see, I use all kinds of things to create the image. I experiment with different materials like sand. One of those pictures was certainly more abstract than usual. When I have an exhibition in Kenya, it amazes me that in this geographical place people tend to lean towards the less abstract work, which is fair. But, yet again it is very difficult for me too. These works are nice because they represent the variety of places that I go. I don’t think I have a style because the material and the subject have a lot to determine how or what idea comes out. It changes whether I want it to or not.

My practice changes all the time and I don’t plan these changes. I can’t plan changes. There are challenges that one faces at a particular time and that influences me. It gives me a chance to reflect on older works. I used to destroy my works, or work over them when I didn’t have a new canvas – but that was another girl, a girl much younger than this one. Now I don’t want my work around me, standing dictates, and that is a deadly thing. I work and move on.

Theresa Musoke, Hartebeest in browns and purple, 1999

Oil on canvas

116.5×79.5cm

My practice changes all the time and I don’t plan these changes. I can’t plan changes. There are challenges that one faces at a particular time and that influences me. It gives me a chance to reflect on older works.