Still blunt, a conversation with Gabi Ngcobo and Misheck Masamvu

From artist Misheck Masamvu’s catalogue Still

In my dream, I and a few other people are in one of Misheck Masamvu’s vintage vehicles driving around Harare. It is not a normal car but rather feels more like a wagon or a poorly refurbished mini bus. It has red fake leather seats on very thin steel frames. There are no seat belts and he is driving like a maniac. The traffic police, much to our anticipation, begin to chase at the vehicle but Masamvu does not stop, instead he accelerates. I am shit scared and start pleading with him to stop, obey, everything, after all, can be worked out. He doesn’t, instead he breaks every driving law imaginable, overtaking in dangerous zones, driving off the road into bumpy construction sites. The police don’t give up their chase. It is a nightmare, obviously. Eventually he stops and leaves the vehicle to talk to the police in private as we look on from inside of the mini bus. Instead of the anticipated hostile interaction between Masamvu and the officers, the conversation appears to be smooth and friendly, they laugh with an easy familiarity, as if everything was always just a game. He ‘oils’ no hands. One has the impression that, if anything, they are the ones who will do the oiling, given the chance.

Masamvu speaks equally passionately about his collection of vintage cars as he does of his artistic process. During my last visit in Harare, a delegation from ICAC – International Conference on African Cultures (ICAC) arrived at Villageunhu to witness the work of younger artists he has been collaborating with and mentoring alongside a well-lit display of his impressive collection of vintage cars. The passion to collect vehicles and the passion to paint have become intertwined. In (insert date) Masamvu inscribed his poem titled “Still” on the body of his VW mini bus from (insert year/model 19…) which he would be seen driving around Harare. Obviously a politically loaded poem, it sent a direct message to the heavily policed city and acted as a direct critique of the Mugabe government that held his generation captive. The poem has inspired his solo exhibitions held at the Goodman Galleries titled Still (Johannesburg May 2016) and Still Still (Cape Town November 2016). Thinking of the 2016 ICAC gathering themed Mapping the Future, a reenactment of a 1962 conference that took place in colonially governed Rhodesia, I cannot help but consider it alongside Masamvu’s Still poem. If Masamvu’s painting are about anything then they are about the inability to map a future – they are a marker of a not-yet existence, a space for un-mapping a dream that didn’t last long enough to sustain a future. Masamvu writes out of a necessity to record the signs. At times these read like non-sense. It is his way of staging a war on a language that has become impossible and perhaps language’s failure to inspire new imaginaries. How does one exit a state of perpetual mourning? “Words on their own don’t do what they are supposed to do,” says NoViolet Bulawayo, the author of the novel “We Need New Names,” a title that reads as a proposition or a cry for exiting a state of ‘stillness’. However this state of being still is not all hopeless. Words can have multiple meanings. In ‘stillness’ there is resilience and there is hope.

The conversation between curator and educator Gabi Ngcobo and artist Misheck Masamvu took place in Johannesburg, South Africa on 3 October 2018.

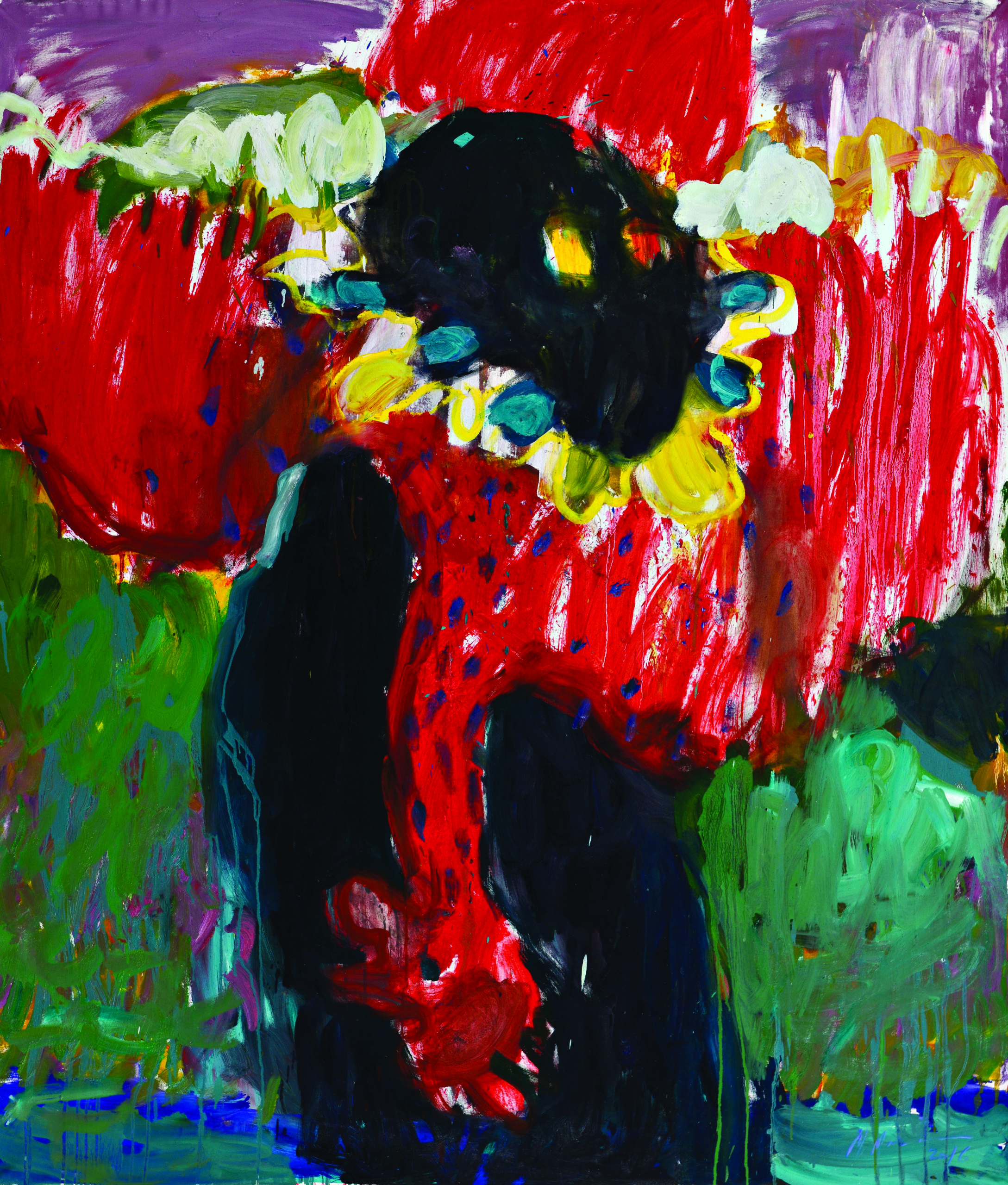

Studded forehead, 2018

Oil on canvas

149 x 131 cm

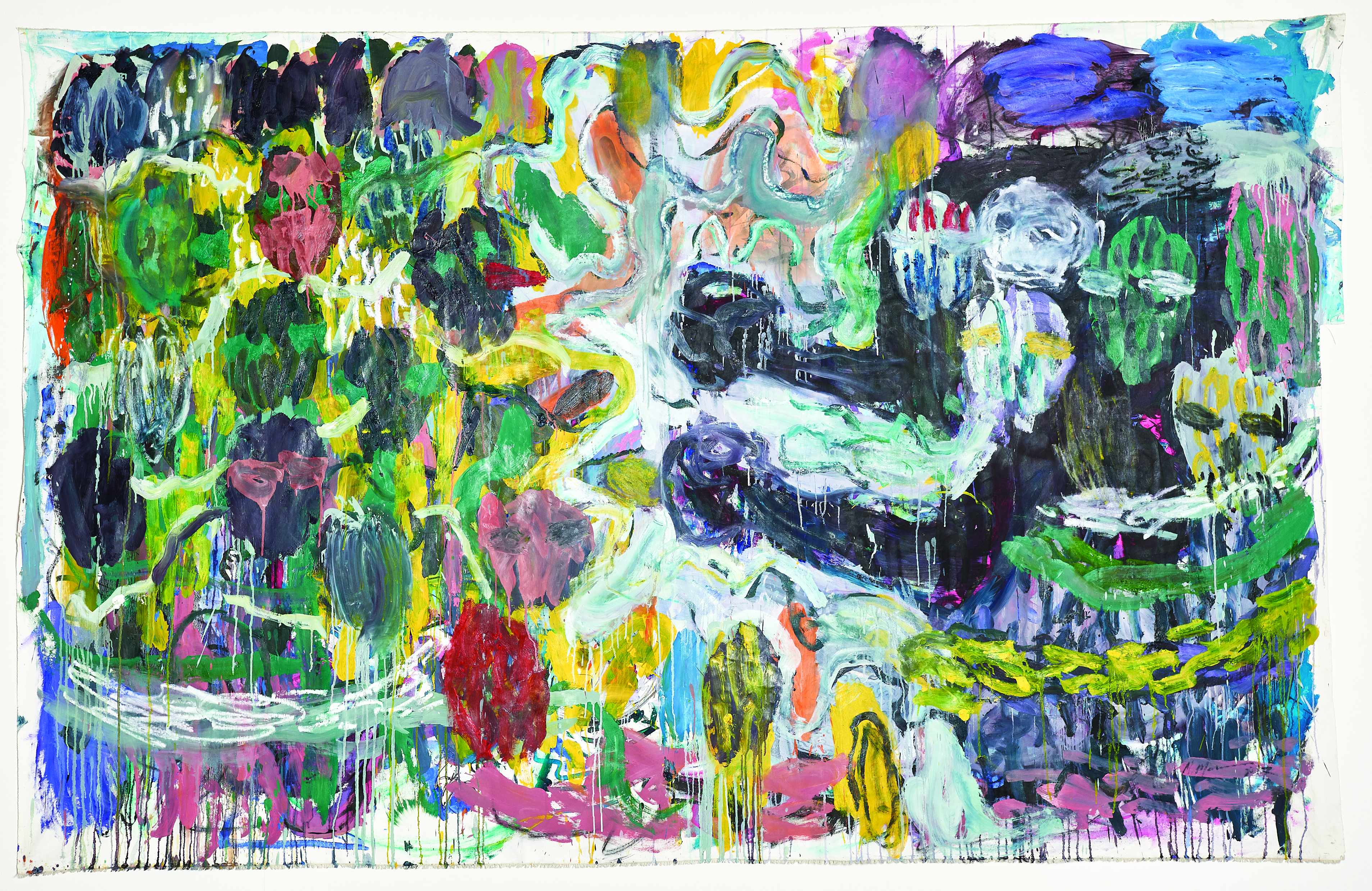

Natural Selection, 2017

Oil on canvas

168 x 270 cm

GABI NGCOBO: I was sent, from the gallery an extensive and quite impressive portfolio of your work dating from … strangely, to me, missing the very first works I encountered of you, at the Dak’art biennale in 2006. Your contribution to the biennale was two paintings, if I remember well… One depicted an upside-down house filled to capacity with people and animals. I remember immediately thinking of Marechera’s rather prophetic novel The House of Hunger (1978). One of the strongest lines in the novel reads: “I could not have stayed on in that ‘House of Hunger’ where every morsel of sanity was snatched from you the way some kinds of bird snatched food from the mouths of babes.” A fitting description of the way I remember that painting, and another more recent one titled Within the Frame (2012); here again the image of a seemingly haunted house is used to suggest a state of desperation…

Describing Marechera’s writing Zimbabwean activist Takura Zhangazha observed that “Marechera wrote not for political reasons or to be politically correct or wrong. He wrote for generations so that they could come to terms with how Zimbabwe has evolved as a country. He was a rebel with a cause, he was a prophetic writer and sought to speak through his writings.” In a way one could think of your work in these terms too…

MISHECK MASAMVU: I kind of enjoyed using the motif of a crowded upside-down house, I guess that was the most complete moment of my twisted mind, or of twisting everything to see how else things can be seen. The house had people in it: some of the people’s heads were chopped off, some had their brains emptied out and one person had transformed into a goat – there’s always that sacrificed individual and there’s always that emptiness, a mindlessness, that I’m always questioning. How can you accept to be in a group and what does it take to be the one who is sacrificed? There was also a cockerel at the edge, looking in this I guess is the only political reference and one that indirectly relates to Merechera’s bird. Most of the things I work with are kind of timed, so politics for me is just a timeline, it’s not a permanent system. Often, I hear people say that I’m doing political activism through my work but I am not. I’m just delineating how these things can expire, because there is a manmade doctrine that has gone beyond humankind, because, as we know, humankind has a tendency of devouring itself… So that’s how I look at it.

Bootlegged Christmas, 2016

Oil on canvas

156 x 135 cm

GN: Your painting style has gone through many changes since Dakar in 2006. I think there was still what I can call a “controlled edge”, and soon after things started to erupt, the energy completely changed. What compelled or inspired you to make that shift?

MM: I guess what happened was that in the early stages of my career I was working with Gallery Delta and within that space I realized that I was in some kind of trap. I began to feel that I needed to define myself with a certain style and a certain identity that I could call mine and own. In essence, what I discovered after university is that I was lacking a conversation with my work, there was no dialogue, the idea was the most important thing but the actual work itself wasn’t. Slowly I started going back to art, allowing my ideas to change, to not remain fixed so that they control me. I was happy to go through that process of embracing what I thought was a build up as the intentional. I guess for me that was the moment when I put myself in a vulnerable position, operated outside my usual comfort zones and became more effective. This is also the reason I can work as a nomad, as I have been doing in recent months.

GN: Good that you mention that, I have been curious about your idea of self-generated residencies. In March this year (2018) you spent a month working from studios in Johannesburg and Berlin, soon you will be in Kenya… Can you talk about this idea of painting in different places, what does it do for you and your work?

MM: I have become a nomad because I am aware that I’m not here permanently and I don’t have that much time. I can concentrate better on what I might actually do, or what actually is coming out of the work – so it gives me a different perspective where I come out of my body and become a foreigner. I become more aware that I’m not in my own environment, and I become a sharper observer. You know, often times we enter places with a stereotypical idea of the place. Look, being here in your apartment feels like we can be anywhere in the world, this is as global as it can be. But of-course there are different realities when you go down into the streets, it kind of puts you in a different kind of mode, you have a different reading of the streets. Not everything is the same. One thing I enjoyed was being here with only one pair of trousers for a month. That was fascinating. One pair of shoes, one pair of jeans…

Bootlegged Christmas, 2016

Oil on canvas

156 x 135 cm

GN: How could you survive with one pair of jeans for a whole month, when did you wash them?

(laughter)

MM: I don’t think I washed them the whole time I was here. I also had a pair of shorts, but I only used them when I was in the house, and when going outside I strictly wore those jeans. It really became like a uniform.

GN: Did you also paint wearing them?

MM: No, I had a work suit in the studio. I wore them between the apartment and the studio. I wanted to have a familiar image, something that people would recognize, my presence became like a pattern that was repeated. It became a routine. I walked everyday. Of greater interest is I spoke to a lot of Zimbabweans on the way, but they actually thought I wasn’t Zimbabwean. I just became very local. That is one thing that interested me, you know, to enter a space with a sense of being vulnerable but somehow when you find your own rhythm to become local most of the other things start to have a different rhythm. So that was one thing that I enjoyed about working in Johannesburg.

Here I also got to work on older works that I recalled from the gallery and bought to the studio. One painting was quite interesting; I had painted it in 2012/13. When I placed it next to another painting it immediately became clear what was missing. It happened quite naturally. I did not dismiss what was already there because there was a foundation, another painting underneath. So, I just carried on with a renewed energy, but it was much more resolved in my mind. The scale and height of the studio space here in Johannesburg, also helped in terms of how I viewed the older paintings. I had a better view here; I could go up to the mezzanine to take some distance from the work. It was a chance to look at my work as an audience whilst creating it, this was very useful for me.

GN: How about Berlin, how did that work out for you? I caught a glimpse of you during the opening of the 10th Berlin Biennale but then you disappeared, into the shadows, your favorite place. (laughs)

MM: I was happy being in the shadows actually, because I was like an invisible company, people are aware that you are there, but you can also disappear… Berlin for me was really like going back to Europe ten years after my studies in Munich, just to gauge whether I still had some kind of connection or footing there. I enjoyed it a lot, also the studio space was bigger, and I guess I was also in the vibe that you and your Berlin Biennale team had created there. Meeting everyone there just gave me a lot of energy; it felt like I am within the current. Now I dream of taking a trip to Japan and having a private moment there.

GN: Why Japan specifically?

MM: Because of my interest in drawing. I still make a lot of drawings actually.

I feel that going to Japan will be very productive for me. I don’t know much about Japan, but I think that there will be that cultural submission, because I’ll be bound or restricted to space, to conform. I will also be able to put my head down and for the first time in a while look at what I’ll be doing.

GN: True, you do. They are beautifully delicate drawings, still with a poetic violence that is inherent in your work. How do you think your drawing practice is critical for your practice as an artist in general? Po

MM: These drawings happen very quickly. I can go through maybe 500 drawings in a week then I get burn out for two years before I can actually go back to drawing again. Most of them are just a search for one line, so I keep on looking for that line over and over. The difference between these drawings and my paintings is that I become very feminine when I’m making them. I think this is when I let my late twin sister take over. I really feel that drawing helps me to embrace my feminine side.

GN: So I guess they can be a way of balancing yourself in the world, of being a well -rounded human, what ever thist means. How does Mishack the nomad operate in Harare, how do you manage to dwell in the shadows there, if at all? A number of people seem to rely or even depend on the space you have created there, which may make it hard to disappear.

MM: In Harare my home is also like an institution.

GN: And therefore, a kind of a station…

MM: In actual fact, I think because of the institutional structure of VillageUnhu and the expectations that come with that, and maybe also the reputation of the place itself, does make it feel like a station. You are absolutely right. Within that station scenario people also often ask, “Where are we going?” Because, what’s the point of standing at the station not knowing where we want to go? But there are very people who are interested in having that kind of conversation. But also, I’ve just realized I’m just a caretaker of that station because I expect all those who are coming to say, “what else can we do?”.

Bootlegged Christmas, 2016

Oil on canvas

156 x 135 cm

GN: Can you explain why you feel the need to organize the VillageUnhu in the way you do. Since I’ve started visiting Harare I’ve seen how you’ve relocated three times, always looking for a bigger place that can accommodate not only you and your family but some artists too. Why is that so important to you?

MM: One part is that I believe in the artists, and it reminds me that I too needed a small nudge at the beginning of my career, a space to define my own freedom. Some of them take a bit long to find that freedom. So, it can feel kind of abusive at some points (laughter). It is not my intention to keep the space open to the extant that it is at the moment. I’m actually looking forward to having a different function to it. I do have moments where I feel I should just shut it all down but I’m also just beginning to be in a space that offers possibilities of doing something and not just being passive within that landscape. It’s good to know that the space can be occupied and used productively.

GN: And can you see it changing the environment in the city, in Harare, in the country, at least as a practice that other prominent artists embrace?

MM: Well, it certainly opens up more doors of possibilities. Imagine having a space where there is a wall, where you feel like you’re just waiting to find the right painting or object to put on that wall. Imagine that this wall is demanding of a certain particular thing. You don’t know what it is but everyday it creates that kind of dialogue. In a way it kind of evokes the spirit of a search; searching for something through others but also feeling like there are things pointing at me suggesting that maybe it is me who is actually not seeing what should be done.

So, I’m no longer looking at this as an opportunity for them, I’m also seeing it as a challenge and question to myself. But unfortunately, the space itself cannot function as a studio for me. The bottom line is, I haven’t seen a particular wall that is inspiring for me to actually work there. My studio is really just a watchtower. It’s as if I’m in a war zone (which is partly true) I have a good view to everything, so, half the time I’m just cleaning the guns rather than shooting at anything.

GN: Can you elaborate, what do you mean by that?

MM: Well, because, the works that I prepare there are always just a surface. They need so much more; they need a space for a conversation. Recently I started inviting other artists to group painting sessions. We actually take easels outside and we use a small green patch on the edge of the yard as an open studio. Now I feel like there’s a conversation happening, I feel I’ve been relying so much on not looking, relying too much on imagining. Now when I’m actually out there looking at things I make myself vulnerable to a new audience all together. I’m happy that this is happening as I’m seeing some good things happening with this group. I’m noticing how others are coming up with new solutions, how we are gaining new life, all of us. Essentially, we are going back to basics, some of it is just observational drawing such as looking at a tree. Half the time I’m not actually seeing a tree, so there is also that. Maybe after 30 minutes of looking I may try to make references to it, to allow for that destructive nature that comes with actually making a painting, where you pour something and wait for a perfect accident.

GN: Yes, which is very apparent in your work because as much as we can’t really say that your work is not figurative it is at the same time not purely abstract…

MM: I think it borrows from both sides; it is really about working from a hard edge to a soft edge. Somehow, it’s also about pouring emotions to it. It can be quite traumatic on one part, and very emotional, but at the same time there is serious control.

GN: How do people often respond when they encounter your work? What is the most common thing that you hear people say?

MM: There are those who say that the work is symbolically loaded. Others just comment on the explosion of colour, they find it abnormal and a little bit eccentric.

GN: Another thing I wanted us to talk about is the role of writing in your practice. Am I wrong to think that writing functions in a similar way to how your drawings emerge, a way of speaking of things differently, a search for some kind of stability?

MM: I’m beginning to write some dysfunctional political commentary, but it’s also really based on the realization that, for me, the politics are no longer outside, they are inside…

GN: Can you elaborate on that? When for you were politics ever outside? The political has never been personal for you?

MM: I mean, just seeing something and trying to comment on that particular thing. You see, Mugabe was too much, he was a person who you wouldn’t want to work internally with. He was not a political figure that you would simply brush next to. He was something that you’d be happy to see from a distance and just describe it. But now we find ourselves in a country where there’s a lot of misinformation and because of that there’s actually a void, you basically cannot use the same tools to analyze anything. I don’t have the same anger issues…

GN: Or maybe you don’t know where to locate the anger…

MM: Exactly. I now start to draw them from inside. Things are now reflecting more as my relationship to my own trauma, which has been there for a long time.

GN: Do you think the poem “Still” still functions the same way post Mugabe?

MM: Yes, it does. I actually was thinking, if we were able to give a title to what we are trying to talk about here it could be, the next statement I would put on that poem is “Still blunt.” Because I was really thinking, is it because I’m still quite direct with my statement or maybe I’ve become less effective? Maybe I’ve become more dangerous, because I’m no longer cutting with sharp things; I’m actually just shredding things. I’m also at a stage where I feel like I’m self-editing, which is quite dangerous especially if it’s a relationship, I mean, we can’t edit people…

GN: Mmm, we can…

(laughter)

MM: But now with a blunt tool!

GN: I guess that’s even more violent, I see…

MM: You see? So, it’s really concealed violence that I guess I’m kind of faced with.

Bootlegged Christmas, 2016

Oil on canvas

156 x 135 cm

GN: I would also like to talk about your cars somehow. I had a dream… (the dream described at the beginning of the interview is told to Misheck.). You have a special relationship to speed, which I suppose makes sense for someone who is primarily a painter, or discourses with the world through the painting medium the way that you do.

MM: I think my interest in speed is somehow a real reality of time. We have been driving from Harare to Mutare quite often recently and I now drive that distance in record time and I found a specific car for that.

GN: A new acquisition?

MM: Yes, that is much faster. It’s quite effective in a sense that I forget that I am actually driving; I guess that’s really the idea. I don’t have to be on the road and participate, the road is just a tool. What I am trying to do is what matters, not to pay attention to what is there. I know it seems like a very reckless approach, but I believe that people who spend more time on the road have a higher chance of having an accident, those who spend less time on the road have slimmer chances… I’m not trying to justify speed but…

GN: But speed is something that feeds you somehow.

MM: Yes, it’s a form of release. To max a car is the most beautiful thing, to push a machine to its limits is actually amazing. So yes, there’s a relationship to how and why I paint to a certain extant. When I’m in the car driving, it’s both like a prayer and also an atheist position.

GN: How so?

MM: What I mean is, it’s like a prayer because I hope to know what is on the next bend, I need to have that kind of faith, that things are going to be all right for everyone who might be in the car with me. At this point, my faith is on a higher level than my vision. There has been near accident experiences when my heart would jump. In those moments the important thing is not to show it but to find a way of explaining it without fear, which is a similar thing when I paint. A good painting needs to hide its flaw very well, that’s how I look at it, when I hide those mistakes by making them seem as if they were something that was always meant to be. I have never been in a situation on the road where I have to put the breaks on, in most cases I actually attack, I see the opponent and my safety major is not necessarily to be safe but to see how near I could just survive. But you see, with painting it’s almost similar, I need to be able to go to that urge, where the painting needs to start to speak as a painting, where my idea is less important, somehow my idea becomes a companion, but I allow the painting to be.

GN: How long does it take you to… let me rephrase, what is the shortest time you have taken to make a painting? Is duration important to you? How do you know when you need to stop?

MM: I think the shortest time I’ve worked on a painting is, – if I’ve had a complete overload, which means I have been thinking about it and I’m paying less attention,– it can happen within hours actually. The hardest part is when a decision of what was meant to be is not technically right, then it can take much longer, but putting it down is the most violent quick thing that can happen. Sometimes I can have a painting that has taken me years and then at a certain moment I just need those few strokes to lift it up and reach a complete transformation.

GN: Such as the paintings that you recalled, for example?

MM: Yes. Because they already have a painting underneath what I do is similar to weeding, I take out the old things and replanting a few fresh things, pruning of certain branches, and then all of a sudden you get to see what kind of forest it is. It’s always like that, a proper walk in the forest, where no tree is more vital than the other. I actually enjoy that struggle that each tree will grow to its max potential, harnessing its essence is what I try to do with every brush stroke.

GN: I saw that one of your cars, the VW beetle, was in an exhibition at the National Gallery in Harare as part of a group exhibition titled Lost and Found – Resilience, Uncertainty, Expectations, Excitement and Hope (2017). You titled the work Beetle of Hope. I know the beetle to be army green but this time it was black. Can you talk about the symbolic function of this car in that post-Mugabe era exhibition?

MM: Yes, it was black in the exhibition, but now it’s back to army green. For me the car was a kind protest. I needed an excuse to make a statement. The exhibition was celebrating what transpired during that Zimbabwean coup/march, whatever it was, in September 2017 and the misfortune of believing that those in power can ever recognize the masses. I wanted to voice my frustration – I honestly believed that I was contributing something during the marches. So, for me it felt like the car, to some extant, was that kind of statement, as a family car – and the beetle and the role of it in the protests. In a way it was one of the tanks, because the during the march it had 15 people on top of it, the same number as the other proper tankers that were there, and it had the same army-green colour then. I guess it was also just good to see how flexible the National Gallery as an institution can be, to be open to something like that. I was very happy that they were able to do that as a reenactment of what had happened in the streets. In the gallery too, there were people on top of the beetle everyday.

GN: Why was the colour of the car changed from army green to black, what was the symbolism around that?

MM: Because I wasn’t happy about the stolen glory of the march, that all of a sudden, the military and Zanu PF thought that they were the ones who actually liberated us from Mugabe and thereby downplaying the role of a mass protest. That felt embarrassing, you know, how can they? So, the car and the colour was there as a reminder of everything that transpired and that it became a different trajectory all together. Now the car is back to its army green colour, well, because I feel that the relationship of the people and the army is now very clear. The army doesn’t have the same friendly position that they had during that week. This moment, with the car inside the gallery was again another form of activism.

Hooks n Dreams, 2017

Oil on canvas

168 x 197 cm

GN: What would you have said if someone had offered to buy the car, as an artwork?

MM: It had no price, so…

GN: everything has a price.

MM: Well, even if someone had proposed to buy it, I guess for me the hardest part was how that would be explained to my children. Their names are inscribed on the car, so, I guess that’s why I do not see it as a commodity. I actually re-created the car as a conversation, as a lesson to my kids. I feel that, perhaps because of my way of driving, or as a painter, you know, I’m always questioning death. I’m really a daredevil; I can be senseless. But somehow with color I see more, I see people closer, I even try to mirror my own life to see how vulnerable life is. Each day I begin to feel like I’m building a legacy, one painting at a time. Inscribing my children’s names on the car is a proposed way of communication to them, to give them a certain kind of understanding of what it means to take something that was discarded and recreate it anew. In Harare many people feel like they want to be part of the car’s story. Others see it as a thrill-ride, whilst others look at it with complete astonishment – that these things we see everyday as carcasses, can all of a sudden possess beauty, that a new story is possible. Our beetle was not a pure restoration but was actually re-sculpted, most of the things were given new purpose and an aesthetic. That’s also why I felt like my children can learn that with great care you can always remodel yourself. The biggest enjoyment of actually being in that car are the conversations that I get through the open window, just the hope I give to a lot of people is gratifying. The true value of it, based on how much I’ve invested in it shocks them.

GN: When I saw the picture of the beetle inside the gallery, the fact that it had of course become a sculpture, made me recall the sculptures you made more than ten years ago, which, like the car were also often black in colour. One of them is a stretcher, am I correct? It has handles on each side and is made out of woven canvases that were then painted in black. There’s a soft one and then there’s the hard one. The hard one is titled Mishack we miss you, from dead mother and twin sister and the soft one titled Correct Mistake. You are not known for your sculptures but every now and then they appear, less frequent than the drawings. How do you situate them in your practice?

MM: Actually Correct Mistake is more of a coffin than it is a stretcher. The one titled Mishack we miss you… was actually a letter from the dead. I wrote a letter to myself, from the dead. The letter is within the artwork, hidden within the bandages. I don’t remember the content of it but I’m sure I wrote something there…

GN: That’s interesting. You made these works whilst you were studying in Munich around 2005/6, right?

MM: Yes, I guess at that time painting and working in color didn’t make sense; I was going through a moment of loss. My mother had just died as well, so both pieces had a… I was creating some kind of a bridge, that is why all the works have handles. I was searching for some kind of support, emotional, spiritual, etc. If you look at Correct Mistake more carefully you will notice that one handle is missing. So, I always want to speak about that missing part… but I think all that I have done through my work is trying to understand my relationship with the dead. Strangely enough I have only seen one dead person in my life, and the dead person was an artist not a family member.

GN: Didn’t you see your mother?

MM: No, I was happy not being able to see her. She was also okay with me not seeing her. Maybe she already knew that something was going to happen because she told me that if anything happens I didn’t have to come back home from my studies in Munich. One other thing that I think about often is the tradition of burying of a twin, when someone who is a twin dies they don’t get buried alone, a makeshift sculpture would have to be made to bury them with.

GN: So, you had a twin sister who died as a child…

MM: Yes, she died just three hours after she was born. I have these constant questions throughout my life; was her life a sacrifice? Can what I’m doing make sense as a way of paying homage or celebrating her life? That follows me everyday and to some extent I’m living with her as a guiding angel. So as much as my love for speed, for example, may seem kind of suicidal, I am also comforted by knowing that I never walk alone. I kind of feel like I’m living a delayed life…

GN: How do you live a delayed life, on speed?

Laughter

MM: Yes, you know, what’s the point of taking caution when you already know the end results? This is the rule I also apply with my work “what’s the point of being cautious?” There is always that urge of not being satisfied, you just keep going after things very quickly, almost like a rat. An Indonesian guy once told me that I’m quite dangerous, that like a rat – I see things, go after them and process them so quickly and then ask, ‘what’s next?’.

GN: Do you dream a lot? It seems to me that dreams are an important part of your visioning.

MM: I forget most of my dreams. But I had a beautiful dream recently. I found myself at an exhibition opening but it was the devil’s exhibition. He showed me three of his paintings, the first painting that was in the exhibition was about angels and what was fascinating was, no wait. I think the first was a self-portrait, but because I don’t remember his image very clearly, I can’t say much about the painting. The second one was about angels, and the angels were very interesting – when I looked closely at the painting I noticed that it had a kind of glitter that made the angels seem like they were moving. You know when you look up in the sky and see shooting stars? It was like that. I asked him if the movement of the glitter was timed and he said, “let me show you how I did the trick.” He took me close to the painting with a magnifying glass in his hand and asked me to take time with each and every piece of glitter, embrace the light and bring it in – once my eye hit on that glitter I noticed that it was actually my eye that was moving. None of what is there is actually changing. I was fascinated by this technique.

After this he took me to see the third painting, which was about the ghost. It looked like just a black canvas, but it had these beautiful greys and a beautiful graphic. But I told him I couldn’t see anything. He told me not to worry it will come to me and indeed the painting started coming towards me and covering the bed I was sleeping on. The hardest thing was that whilst parts of the canvas were coming towards me they were becoming very heavy. I started to feel uncomfortable and cried out telling him that this was too heavy. I was getting buried under these things. So, whist I was fighting this I woke up. But it was very interesting and frightening at the same time. It’s hard to forget a dream like that.

Conflicted, 2017

Oil on canvas

160 x 136 cm

Resources

Interview and images courtesy of Goodman Gallery.

Access more information on Misheck Masamvu’s work here.