The Indian in Drum magazine in the 1950s

Text by writer and curator Riason Naidoo

This article is an edited version of the ‘Introduction’ to the book The Indian in Drum magazine in the 1950s (Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2008) by the author that followed the photographic exhibition he curated by the same title (2006), which toured museums in South Africa (2006-2011).

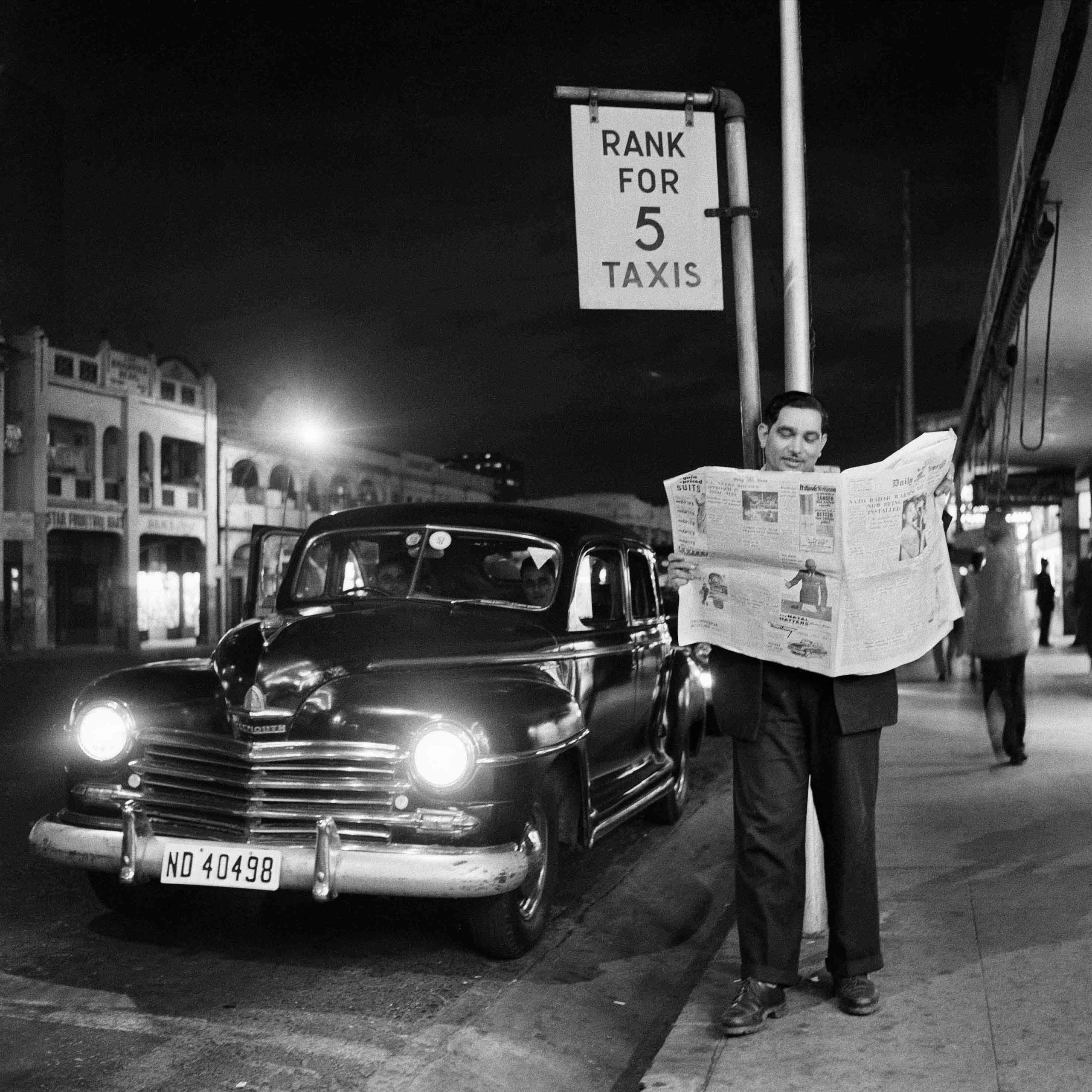

Ranjith Kally, ‘Rank for 5 Taxis’ – Durban, 1958. © BAHA.

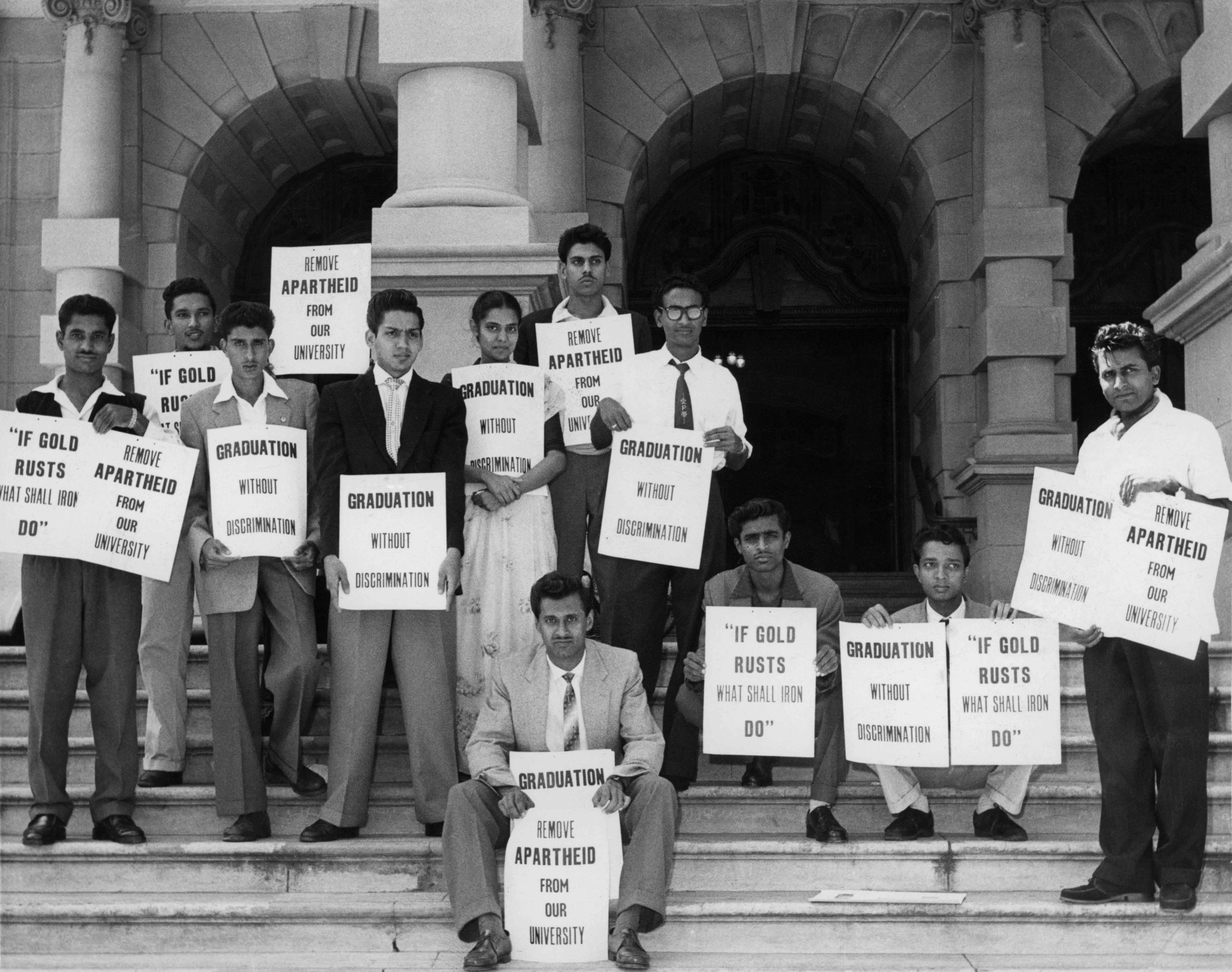

Ranjith Kally, Natal University Students picket outside Durban City Hall, 1958. © BAHA.

In the late 1970s, after school hours, I would spend my time at my father’s small stall in the Victoria Street Market, playing draughts on the checker boards of stiffened carrier paper bags until the shutters to the main entrances were rolled down. The market was notorious for its street fighters, its links to the underworld gangs and some of the biggest football clubs in Durban. It was also a spot where runners of the big gangs could illicitly dispense of imported goods – Hardy Amies silk ties from London, gold watches, leather jackets, and designer cigarette holders – for a fraction of the store price. It was in this environment that I encountered many stories of ‘Indian’ gangsters and football players and some of the famous dance halls. Even within my family there were professional football players, tough street fighters activists and ballroom dancers. Names such as the Dutchenes, the Crimson League and the Salots constantly recurred when speaking of gangs in Durban. And Dharam Mohan and Links Padayachee are still remembered as two of the most gifted footballers the country has produced, at the time when Aces United and Avalon Athletic football clubs filled Curries Fountain to the brim.

Ranjith Kally, Pataan – Durban, 1958. © BAHA.

Stereotypes of the ‘Indian’

But this is not the image of the ‘Indian’ that has generally been presented in popular culture in South Africa. Instead, the more commonly held notions of ‘the Indian’ – constructed over a period of time, first under colonialism and later under apartheid – are dominated by an image of a wealthy ‘Indian’, often in the form of the cunning shopkeeper looking to extort the customer and exploit the worker; or the traditional and often backward ‘Indian’, one who follows in the old cultural traditions of arranged marriage, caste, and other age-old static religious practices.

Many of these stereotypes, created under colonial and apartheid South Africa, perpetuate to the present day. These notions have deep roots that can be linked to certain anti-‘Indian’ sentiments that evolved out of an ‘Indian’ economic threat posed to whites in nineteenth century Natal, a British stronghold in colonial South Africa. It reveals that stereotypes are extremely powerful and the perpetuation of them can continue for centuries. The recent decades of separate development along racial lines under apartheid further contributed to colonial and imperial ideas of the ‘Indian’ subject and the entrenchment of such thinking into the present.

These stereotypical notions of the ‘Indian’ were also at odds with much of my own experience and the stories I had heard from my family. At times I wondered if the family narratives were not a romanticised version given an exaggerated importance to compensate for the dehumanizing effects of apartheid. Motivated by the passion with which these stories were related, I began to look for representations of other ‘Indian’ identities than the limited ones already circulated in colonial and apartheid South Africa.

Drum photographer (possibly Ranjith Kally), God’s Chillin Gotta Work, 1957. © BAHA.

Family stories and photos

I started to search for traces of this in my family’s archives. A trip from Johannesburg, where I was working at the time, to Durban led down a dead-end road when I discovered that all the old family photographs had been lost in the various moves after my grandparents had passed away. This effectively effaced for me any visual reference of the early family history: the football teams, the Junction house where my great-grandfather brought up his family on the small farm plot; the Sea View house where the family later moved to in the 1950s. This sense of loss is described by bell hooks,

“I remember giving her the snapshot for safekeeping; only, when it was time for me to return home it could not be found. This was for me a terrible loss, an irreconcilable grief. Gone was the image of myself I could love. Losing that snapshot, I lost the proof of my worthiness.” (1)

This absence of pictures revealed to me the evidential power of a photograph. Where were the vestiges of the often talked about social clubs, extraordinary gangsters, journalists, boxers, golfers, football players and dancers that related to the ‘Indian’ experience that I had overheard my family tell over and over again? Did this only exist in their imagination? The search was becoming frustrating and the intention of paying tribute to this era was beginning to seem like a far-fetched fantasy.

Then some weeks later, quite by accident, I came across copies of Drum magazine from 1955 as I was browsing through old journals in the basement of the Africana Library at Wits University. As I paged through the yellowed pages of the magazine – usually associated with South African black ‘African’ history, and the freehold township of Sophiatown – my heart skipped a beat…edition after edition, month after month, unfolded personal stories on the ‘Indian’, and illustrated with exquisite photographs, unlike anything I had encountered before. Here was a legendary archive of images and text that spoke of other more interesting ‘Indian’ identities that, to my great surprise, no one had previously cared to mention. The stories I came across in the magazine issue evoked the legendary names that I had heard of in my youth. There was all this and more.

Using the Drum archive, I explore the representation of the ‘Indian’ that challenge the long held and dominating notions of the ‘Indian’ thus far portrayed in public, official and private accounts. I have chosen to focus on the 1950s because it is the era intrinsically linked to the legend of Sophiatown, Drum magazine and the epitome of black ‘African’ life in the country. It was the decade that saw a South African Black equivalent of the Harlem Renaissance, which took place in the United States a few decades earlier. It is also the decade when there was some degree of comparative tolerance before apartheid’s pernicious tentacles gripped society with the violent killings in the Sharpeville Massacre of March 1960. By focusing on the ‘Indian’ in the fifties I draw upon articles and photography in Drum magazine to reveal an alternative view of ‘Indian’ life that is in stark contrast to the limited state portrayals of the ‘Indian’ widely propagated under apartheid. The insight offered to ‘Indian’ life in Drum, often captured by ‘Indian’ journalists and photographers from within the same communities, is an existence that was contemporary with Sophiatown. With such an extensive archive of the ‘Indian’ to draw on from Drum it is also surprising that this has been overlooked in the re-interpretations of Drum since the 1980s.

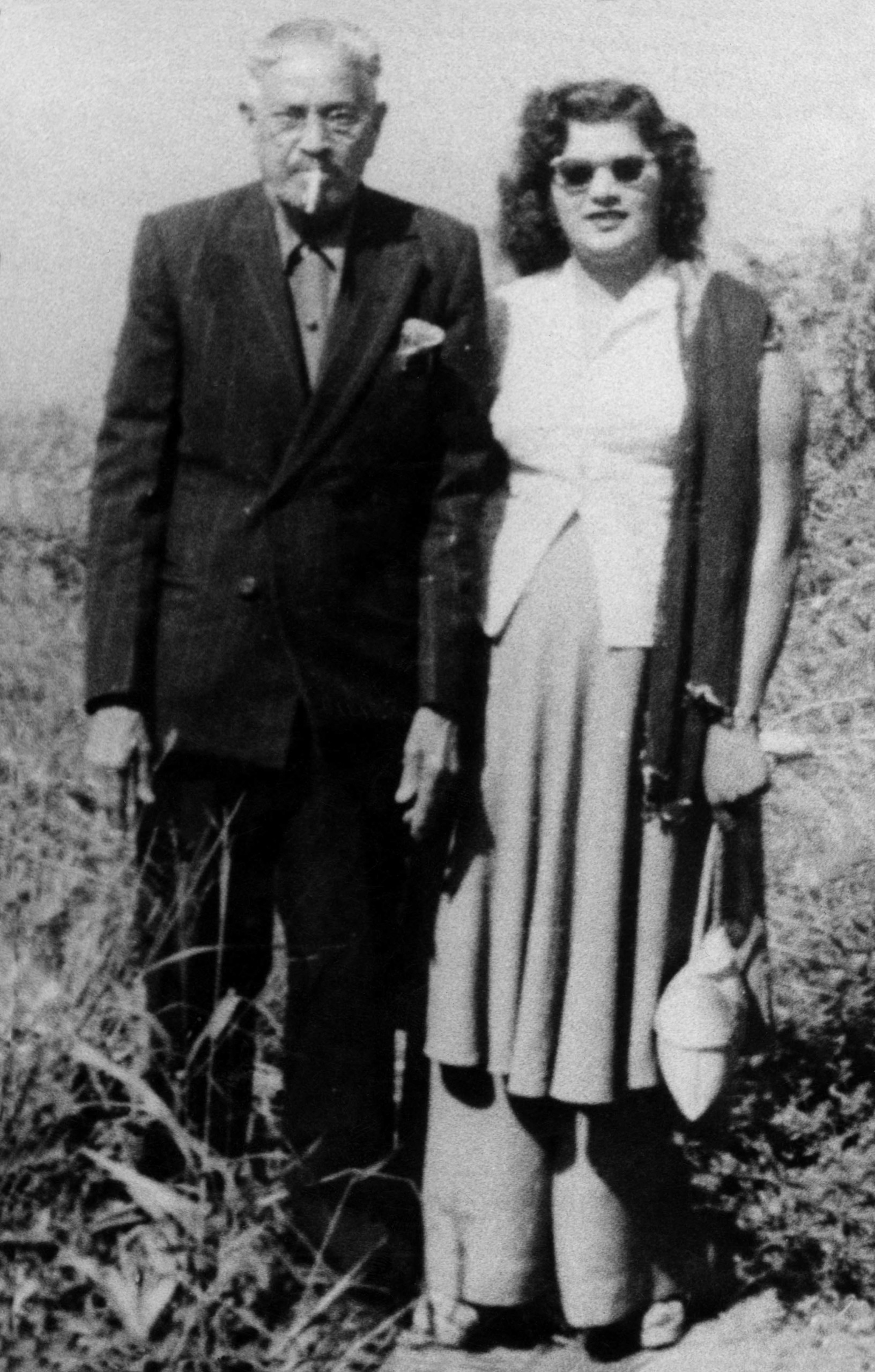

Unknown photographer, Moga & Saras Naidoo (author’s parents) – Durban c.1969.

Using the Drum archive, I explore the representation of the ‘Indian’ that challenge the long held and dominating notions of the ‘Indian’ thus far portrayed in public, official and private accounts.

Photography in Africa

What I did not do is look at all material in Drum equally. While most portrayals and representations of Drum thus far have mainly focused on Sophiatown and black ‘African’ life and contributions, this investigation focuses on the specific portrayal of another South African Black identity in the famous magazine, namely the ‘Indian’, for ‘new’ evidence of other more complex ‘Indian’ identities and experiences. Before exploring the ‘Indian’ identity in Drum it will be helpful to explore historically perceived notions of who, or what, the ‘Indian’ is and to look at the role of photography in constructing and perpetuating colonial power relations. Clare Bell, Associate Curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum at the time of the In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present exhibition there in 1996, argues in the exhibition catalogue that the photograph has also long been an imperative tool in ethnographic depictions of the African continent propagating myths of the Other as documents of real life to the West. These ‘scientific’ representations conformed to specific cultural expectations where the photographic image – seen as mechanically created with minimal or no human agency – was relied upon as an unquestioned exact science.(2) My study also reveals the play on ‘Indian’ stereotypes by the state towards its objectives of projecting a better self-image abroad. Photography remains integral to this discussion of stereotypes and proves invaluable in contesting them via the ‘Indian’ identity in Drum magazine in the 1950s and through the images in the exhibition.

hooks says that photography may help us to reconstitute images of ourselves so that we may imagine ourselves in new and liberating ways that may “transcend the limits of the colonizing eye.” (3) The photos I selected from hundreds of thousands of negatives from the Drum archives of the 1950s in the corresponding exhibition reflect on these ‘Indian’ identities hidden from official and colonial representations.

The use of photography in self-representation, where in this case, ‘Indian’ photographers from within ‘Indian’ communities have privileged access to and enjoyed the trust of that community, reveal more insightful instances of the ‘Indian’, outside of the experience or knowledge of the ‘official’ gaze and other ‘racial’ gazes – an insider’s view if you like. This has often been a threat to the official and frequently constructed representations of oppressed people presented by colonial regimes to reinforce the power relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed. Supporting this view, Nigerian-born artist and art history lecturer in the United States Olu Oguibe quotes colonial photo historian Nicolas Monti on nineteenth century photography, who asserts that the authorities of European colonies in Africa were well aware of the danger of the ‘natives’ “getting possession of this means of expression and using it as an instrument of subversion by showing the true conditions of their people.” (4)

Ranjith Kally, Amaranee with bike – Durban, 1957. © BAHA.

The use of photography in self-representation, where in this case, ‘Indian’ photographers from within ‘Indian’ communities have privileged access to and enjoyed the trust of that community, reveal more insightful instances of the ‘Indian’, outside of the experience or knowledge of the ‘official’ gaze and other ‘racial’ gazes – an insider’s view if you like.

Drum magazine

My research explores and interprets the representation of the ‘Indian’ found in Drum magazine in the fifties according to various themes such as the ‘Indian’ underworld, love across racial lines, modernity, the ‘Indian’ woman, poverty, politics, sport, entertainment, etc. It also focuses the spotlight on the individual characters that epitomised these worlds. The text and accompanying photos in Drum provide a primary source for insight to ‘Indian’ experience represented by ‘Indians’ themselves via the 1950s. With sensitive accounts by the Durban photojournalist and editor G.R. Naidoo and others, this archive reveals ‘Indian’ identities that openly defy the stereotypical notions imposed on ‘Indians’, personalities who were known not only within their communities but also throughout the length and breadth of the country and the continent, wherever a copy of Drum was distributed. And we know that Drum was distributed very widely indeed.

Nigerian born, New York based curator and art critic Okwui Enwezor states that,

“Bailey expanded the parameters of Drum so that it became a quasi-continental organ. Added in succession were editions in Nigeria (1953), Ghana (1954), East Africa (1957), and Central Africa (1966) … At the height of its popularity, Drum enjoyed enormous readership. Even a North American and West Indian edition was distributed. The magazine’s circulation per issue stood at 450,000 copies, reaching far into many literate, cosmopolitan areas of Africa.” (5)

Through this process of exploration and recovery, I offer a glimpse of alternate ‘Indian’ identities that contribute to redefining perceptions of the ‘Indian’ reinforced under the separate development policies of apartheid.

G.R. Naidoo and photographer Ranjith Kally, two figures emanating from within the ‘Indian’ community, whose invaluable contributions in photography are evident in Drum, offer important and refreshing takes on the ‘Indian’, which have for one reason or another been overlooked in the retelling of South African Black stories after 1994. Their own marginalisation in the retelling of Drum’s remarkable legend is closely related to the dismissal to the margins of the realities that they were so instrumental in recording. Their inclusion in this discussion is imperative as chroniclers and no discussion on this topic would be complete without it.

Drum photographer, Mr Moosa Abrahim ‘Old Man’ Salot & BB Salot, 1952. © BAHA.

Moreover, in my investigation for material to speak about an ‘Indian’ history it was photography that kept recurring for me as a tangible reference. It was photographs that I instinctively grasped for to validate this existence when initially searching through my family archives. “Look here it is!” I could imagine myself saying, recalling Roland Barthes’ assertion of the photograph possessing an evidential force, and suggesting “the gesture of the child pointing his finger at something and saying: that, there it is, lo!” (6)

Okwui Enwezor makes a compelling argument that photography should be used by Africans to “re-appropriate images of objectification and transform them as images of our own creation”. (7) With this in mind the images selected from the Drum archives for the corresponding exhibition reveal insights that contest limited official notions of another one of Africa’s many identities: the South African Indian. Edward Said too, many years before Enwezor, articulated the use of photography among other popular visual mass media as having the potential to meaningfully contribute to the restoration of lost memory and history. (8)

The challenge of articulating a more multifaceted ‘Indian’ self through the prism of the 1950s in Drum is an ambitious task, especially since the terrain necessarily includes discussion around broad issues on race, identity politics, class, gender, representation, history, memory and politics. My intention is that through this inquiry more complex notions of the ‘Indian’ will emerge that can be elaborated upon; the restoration of memories can begin, and those legendary individuals long cast in the shadows – whether they be colourful jazz personalities, tough-as-nails gangsters, woman stunt riders or those who took their pictures and wrote their stories – can finally be acknowledged. The argument for a broader, more representative and complex ‘Indian’ identity gains momentum.

Ranjith Kally, Rita Lazarus – Miss Durban, 1960. © BAHA.

The re-reading of Drum magazine since the 1980s

The visual and written Drum store of Black experiences from 1951-1984 reveals a cosmopolitan fluidity. The role of photography proves vital in Drum and integral to this exploration in demonstrating the traces of a more vibrant lived experience. The Drum staff knew the importance of the photograph in bringing home the realities to their readers. This recording of experience was far removed from the official white gaze and official representations of Black life discussed earlier.

The numerous re-readings of Drum that perpetuate the idea of the magazine as an exclusively ‘African’ one, defy the intentions of founder Jim Bailey and editor Anthony Sampson, who did not want the magazine to be seen as only focusing on black ‘Africans’ but on the broader Black community. These re-readings have contributed to effectively effacing the various other vibrant histories within the magazine in the restoration of a broader Black memory post-1994, which serves to deny the complexity and diversity of a country like South Africa that is wider than the black/ white divide. This skewed portrayal refutes a multifaceted depiction of Africa too by subscribing to the colonialist views of the continent as a homogenous one.

Emerging out of a repressive and inhumane history of subjection, the making of public memory can still be a contested one in a democracy like South Africa. In countering hegemonic depictions, the intimate portrayal of a Black sub-culture and contested identities of that culture can stress the plurality of Blackness and what it means to be African, the diversity of the country’s histories, and the heterogeneity of the continent. This is a necessary process of healing in the context of newfound freedom where the former subjugated people reclaim their sense of self and repossess their own histories.

The process of seeing more ambiguous and contradictory images of South African Indians can be initiated. Dignity can start to be restored through reflections of a more emancipated and confident ‘Indian’ self. Cross-cultural conversations, despite having been officially repressed by the state, are revealed through pictures as an inevitable process of living in a multicultural context. The photographs speak loudly and confidently and provide material reference to repressed histories, blurring the boundaries between myth and reality.

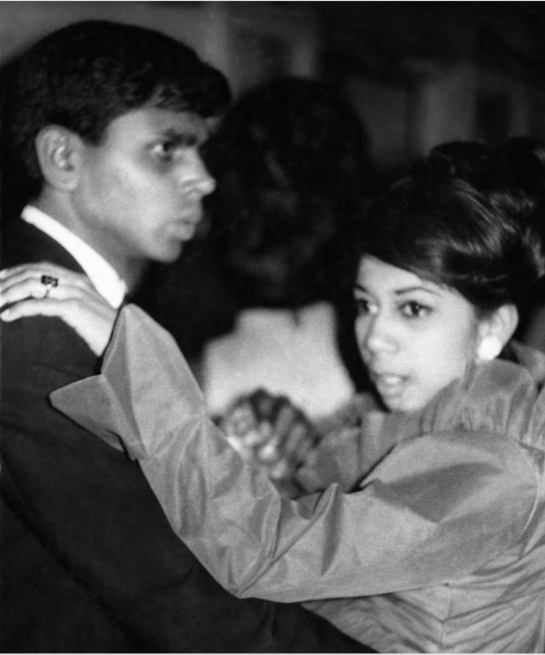

Ranjith Kally, Ballroom Champs – Durban, 1956. © BAHA.

Emerging out of a repressive and inhumane history of subjection, the making of public memory can still be a contested one in a democracy like South Africa.

Personally connected to the photos and the history

And in no way do I play a dispassionate role in it! The photographs and investigations into this ‘Indian’ experience do not speak to me purely in my role as a researcher or curator assembling images based exclusively on aesthetic criteria.

The depiction of Ballroom and Latin American dance couple Runga Naidoo and Violet le Tange evoke for me memories of my parents dancing to the Dukes Combo Band on Saturday evenings at various venues around Durban. The images of Curries Fountain in the exhibition recall many visits to the stadium in my youth, when I accompanied my father to watch Manning Rangers F. C. (for whom his younger brother Sivarungan played in goals) and Berea F. C. in the 1970s. The physical fist fights (as recounted to me by my father and his elder brother Nithianundhan) often took place in the context of the local football clubs they founded and managed, such as Spartans F.C. in Sea View (near Queensburgh) in Durban, then a mixed area. Some of their encounters at football grounds, especially in Overport with Manning Rangers F. C. (founded in 1928 by another G.R. Naidoo and managed by his younger brother R. D. Naidoo also known as ‘Mac’), revealed the deeper links between football clubs and gangs in Durban. My granduncle Thumbi Reddy was a talented left-winger (also known for handling himself with his fists) of Crimson League F.C. that was competing in the central Durban area since 1900, along with the Blue Bulls F.C., Sydenham Unity F.C. and the Pirates of India F.C. (9)

The club had links to the notorious Crimson League gang, which counted among its three hundred working class ‘Indian’ gang members its football players and supporters. Thumbi’s wife Ruby was a close acquaintance of B.B. Salot, who is depicted with her father ‘Old Man’ Salot. Both ‘Old Man’ and ‘B.B.’ headed the Salot gang in different eras. The portrayal of the tough underworld calls to mind my experience of growing up around the Victoria Street market, and ‘Uncle Mac’s’ Stiles gang, that was linked to Manning Rangers F.C. The day after they had beaten up some members of the gang, not knowing they were from the notorious crew, approximately twenty members of the Crimson League gang descended on the market and cornered my dad and his brothers at their stall, only to be saved by ‘Mac’ who put himself in front of the gang and challenged them, “If anyone of you want to get to them [referring to my father and his brothers] you’ll have to get past me first.” At which point the twenty strong posse turned and left the top market.

So these images in the exhibition and book are not only aesthetic and historic citations. I am deeply connected to these identities and stories that are evoked in the photographs, in which I see – as Edward Said quotes Malek Alloula, Algerian author of The Colonial Harem (1986) – ‘instances of myself’ and my own fragmented history in these pictures. (10) And I suspect that I am not alone in this.

Jürgen Schadeberg, Football supporters at Curries Fountain – Durban 1952. © BAHA.

Ranjith Kally, Treason Trial – Pretoria, 1958. © BAHA.

Inspired by the stories in the exhibition and book, Naidoo co-produced and co-directed, with Damon Heatlie, the documentary Legends of the Casbah (2016), that elaborated on the Drum project with oral histories, interviews, and family photo albums based on those individuals originally featured, whilst new characters and archives emerged that enriched the telling of the broader narratives.

This is an on-going project that first started in 2003 with seven exhibitions on the work of Durban photographer Ranjith Kally — curated by Naidoo — in Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town, Bamako, Barcelona, Vienna and Saint-Denis (Reunion Island) from 2004-2011.

Born in Chatsworth, outside Durban Riason Naidoo is an independent curator, writer, filmmaker and artist, who has been living in Paris since 2018.

Notes

(1) bell hooks. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life” in The Photography Reader (2003) edited by Liz Wells. London and New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 389.

(2) Clare Bell. “Introduction” in In/sight African Photographers, 1940 to the Present. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996, p. 11.

(3) bell hooks. Ibid, p. 394.

(4) Olu Oguibe. “Photography and the Substance of the Image” in In/sight African Photographers, 1940 to the Present. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996, p. 233.

(5) Okwui Enwezor. “A critical presence: Drum Magazine in context” in In/sight African Photographers, 1940 to the Present. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996, p. 182.

(6) Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida (translated by Richard Howard). New York: The Noonday Press, 1981, p. 5.

(7) Okwui Enwezor and Octavia Zaya, “Colonial Imaginary, Tropes of Disruption: History, Culture, and Representation in the works of African Photographers” in In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present (ed. Okwui Enwezor). New York: Guggenheim, 1996, p. 22.

(8) “Two concrete tasks… strike me as particularly useful. One is to use the visual faculty (which also happens to be dominated by visual media such as television, news photography, and commercial film, all of them fundamentally immediate, ‘objective’, and ahistorical) to restore the non-sequential energy of lived historical memory and subjectivity as fundamental components of meaning in representation. Berger calls this an alternative use of photography: using photomontage to tell other stories than the official sequential or ideological ones produced by institutions of power… Second is opening the culture to experiences of the Other which have remained ‘outside’ (and have been repressed or framed in a context of confrontational hostility) the norms manufactured by ‘insiders’” in Edward Said, “Opponents, Audiences, Constituencies, and Community” in Art in Theory: 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (edited by C. Harrison and P. Wood). Oxford: Blackwell, p. 1088.

(9) C. G. Henning, The Indentured Indian in Natal (1860-1917). New Delhi: Promilla & Co., 1993, p.136.

(10) Edward Said, Ibid, p. 1088.

CREDITS

Note: With the exception of the photo Manning Rangers Football Club, all images appear in the book “The Indian in Drum magazine in the 1950s” by Riason Naidoo (Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2008).

SOUTH SOUTH shares its gratitude to Riason Naidoo for allowing the platform to publish his work.