Creating an Engine for Art, Democracy and Justice in the South

A conversation with María Magdalena Campos-Pons about the South as a state of mind

Since 2017, Cuban born artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons has found herself in an ostensibly unexpected part of the world – Nashville, Tennessee. However, for her, it was destiny. After many years spent in Boston, where she established an experimental and highly multidisciplinary project space, and working as an internationally recognised artist, Campos-Pons decided to accept a long-standing invitation to be a professor of Fine Art at Vanderbilt University the same year she was invited to produce new work at documenta 14 in Kassel, Germany. In North America’s deep South, a region where the Ku Klux Klan was born and the civil rights movement later had some of its most significant moments, Campos-Pons has built what she called the Engine for Art, Democracy & Justice. In this powerful seminar series, she is driving a dynamic vision of various notions of the South that compels a profound reconsideration from the North.

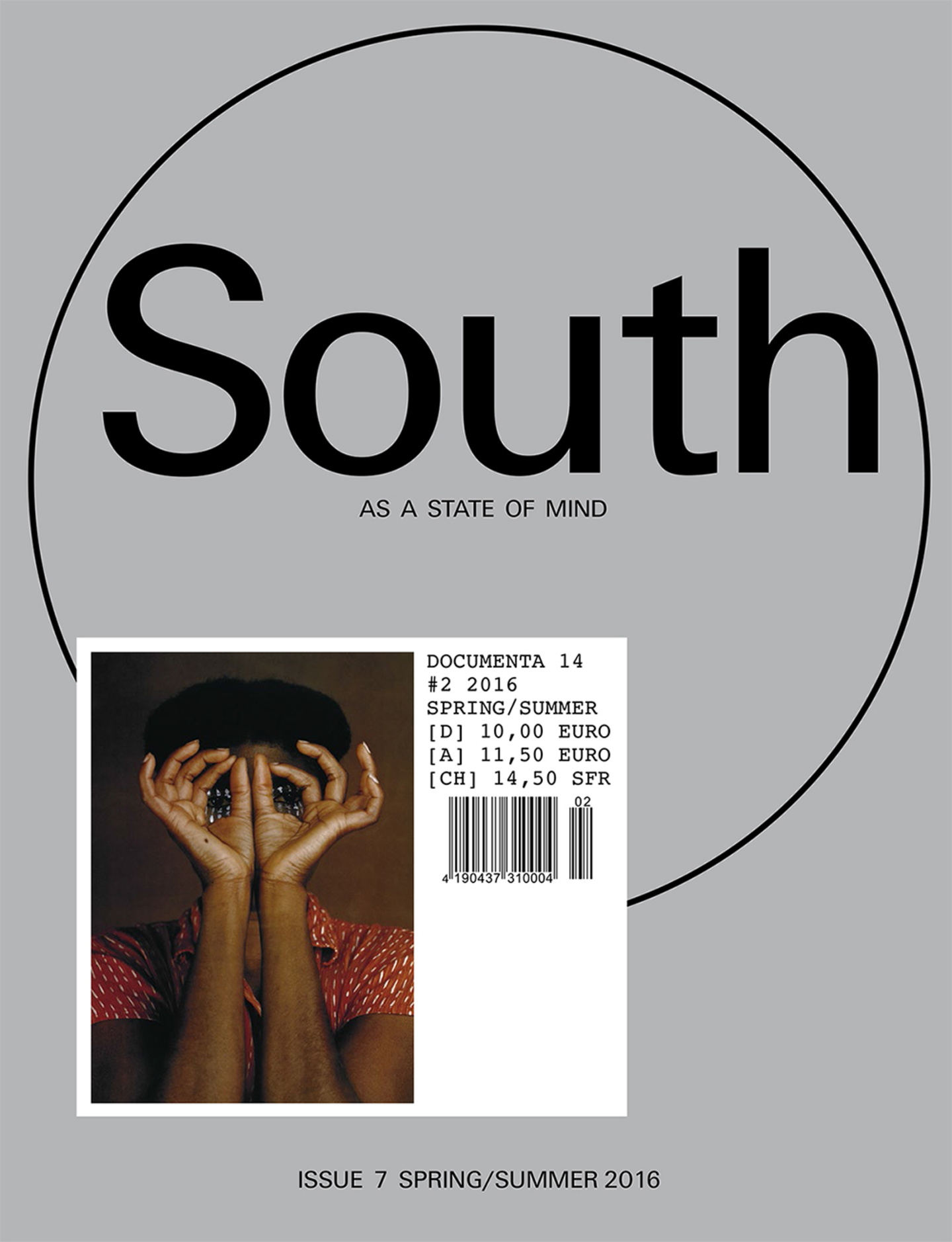

Issue #7 [documenta 14 #2], of South as a State of Mind, a magazine founded by Marina Fokidis in Athens in 2012, featuring María Magdalena Campos-Pons on the cover. From early 2015, the magazine temporarily became the documenta 14 journal, publishing four special issues edited by Quinn Latimer, documenta 14’s Editor-in-Chief of publications, and Adam Szymczyk, documenta 14’s Artistic Director.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, The House, 2013, diptych, Polaroid Polacolor Pro 24 x 20 photograph, 24 x 20 inches (61 x 50.8 cm)

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): Let’s start off with how you landed up in Nashville Tennessee and what led to the establishment of Engine for Art, Democracy & Justice (EADJ)?

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (MMCP): I was invited as a professor of Fine Art at the University of Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee a few years ago. I accepted the position in 2017, the year that documenta 14 took place and then I took a year out to go to Athens and Kassel to work on the documenta project. I was a visiting artist at the Fritz Museum – which is the museum of contemporary art here in Nashville – when I had a solo exhibition there in 2011. I was invited at the same time to present a lecture to the graduating class at Vanderbilt University. And this created a kind of enthusiasm about the University extending an invitation for me to consider to come to Vanderbilt. It was a great experience, but at that point in 2011 I couldn’t see myself in any way in Nashville in Tennessee. I was so established in the North East, in Boston, in Europe, I come from Cuba. But anyway the conversation continued and by 2017, I did very much consider the proposal to be in Nashville. There were a lot of caveats that were valuable and I was really curious about what it meant for a woman of my heritage, a woman of my geopolitical and cultural background to be here – in this particular state of Tennessee, so charged with the history of America, and especially Black America, in this particular time. So I did what I call my “back-peddling” from the North to the South. And every decision that I made in that moment, I’m so happy that I did. I believe that one finds oneself where one needs to be at certain times. And I believe that it is perhaps destiny, or a series of conditions that send you in certain directions. It was precisely the place to set in motion ideas that I had been playing with and thinking of for such a long time.

In 2003, I opened an alternative gallery – a very risky gallery project – in Boston. It was called GASP: Gallery Artist Studio Project. It became a very charged centre of activity in the city of Boston. I knew the gallery was doing well and the programme was interesting when somebody travelled from New York to Boston and they were coming to see two places – GASP and the ICA of Boston [laughs]. The reason why I mention GASP is because there were so many ideas that were initiated in this small project. The idea was shifting a little bit what the curatorial field is. The artist could have ideas too that could enter or intercept the curatorial field as a continuum of their own creativity. I started this project in which every single exhibition was curated by an artist. And it was a thematic underline, and this always had a connection with the artistic process as well. We artists always try to locate ourselves in a group. We form a clique, wanted or not wanted, of an aesthetic, philosophical, ethical kind of grouping. It was a natural thing to do. But I was also interested in creating an intersectional conversation with every discipline. I was married at that time, living with a very active composer – Neil Leonard – an individual thinking in a way that was also interdisciplinary. So we joined in the idea of music and art coming together. This is the way that we met in 1988. In that moment it didn’t have the centrality that it has now. What Neil Leonard and I did in 1988 was starting to pioneer an idea that is very common now, but it was not at that time.

So in 2003 we opened this space and we invited engineers and philosophers, astronomers… You had many artists exhibiting in that space, like Stanely Whitney, who at that time did not have a gallery. Carrie Mae Weems premiered a work that she had made in Italy at GASP. I remember Okwui Enwezor arriving there, entering the room and saying “Magda, who is paying for this?”… It was a solidarity group. I called the project the engine. GASP was moved by the engine. It was about solidarity, about bringing visibility of fundamental ideas that we were curious about and hungry for. Now almost 20 years later, I’ve come to Vanderbilt, a very powerful research university in the South of [North] America. It’s called the harbour of the South for better or worse. But a very powerful institution. The fundamental idea for EADJ was literally presenting the question of what is the role of the artist, what is the role of art, what can art do, how art can insert itself in the question of what is fundamental in this particular time. For me, one of the most pressing and difficult questions of our time is the relation of North-South. And looking at visions of the South – looking at our current situation – our current president talking about the South as “shithole countries”. So [I questioned] what is there to be learnt, to find, to exchange and consolidate of importance in the South that can be a lesson of new knowledge. I was interested in pushing forward a dynamic vision of the South that forces a reconsideration from the North. When the aspiration is the North as the destination, what we can learn from the South, from the connections and the points of circularity of the planetary South? That is fundamental to the ideas for the Engine for Art Democracy and Justice.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Fine Arts (John Russell/Vanderbilt University)

For me, one of the most pressing and difficult questions of our time is the relation of North-South. I was interested in pushing forward a dynamic vision of the South that forces a reconsideration from the North. When the aspiration is the North as the destination, what we can learn from the South, from the connections and the points of circularity of the planetary South?

María Magdalena Campos-Pons and Neil Leonard, Matanzas Sound Map, 2017, sound and sculptural installation, Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA), documenta 14, Athens, photo: Angelos Giotopoulos

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, The Seven Powers, 1994, Cibachrome photos with over painting, black and white photos framed, installation varies in size

SS: Could you speak a bit about the title of the fall programme – Living in Common in the Precarious South(s) – the plural Souths, and how it was conceptualised with Marina Fokidis?

MMCP: So this is important, the EADJ, besides being an online platform that reaches out worldwide, is also a class, a seminar. You as the viewer will see 8 episodes, but there is a class behind those episodes and the seminars follow. Most of the questions that you hear in some of the seminars came from the students in the class. EADJ was conceived as a transinstituional project. I was thinking about Nashille having the very first historical Black college in the country and in the city, Fisk University. I looked immediately for a collaboration with Fisk University and Fritz Museum.

So it’s serving these two directions, two constituents. The thematic approach for EADJ was thinking about the Global South as political, cultural and also as a historic set of conditions. The South is not only geographic, but almost an idiosyncratic way of approaching things. In a reconsideration of the representation of the South – thinking of phrases such as “going South” – we want to shift, to change all of that. There were many important things that contributed to starting the conversation about Living in Common in the Precarious South(s). My own participation in documenta was an important moment. Remember documenta 14 was launched with the idea of “Learning from Athens”. So my entire project was about “Learning from Athens”, but I brought it to the South of the Caribbean. Matanzas, the city where I was born, is considered the Athens of Cuba. Nashville, Tennessee, has a Parthenon that was built in this city as part of the centennial celebration. It is made of concrete and cement. So this is an interesting set of circumstances. So I started thinking about this triangulation, this continuum, Athens as the place that gave birth to the idea of Democracy in the West. I remember when Adam [Szymczyk] invited artists to documenta, he asked us to bring a book for the documenta library, for the archive, and I chose a book written by a Matanzas born writer, Miguel A. Bretos, called Matanzas: The Cuba Nobody Knows. In the very first page of the book he describes Matanzas as the Athens of Cuba. Matanzas was the cultural centre of every possible idea of illumination – lawyers, doctors, poets, theatre, music. It was interesting, this reading of the North as defining the South in a way, but the idea that the Western canon is coming from the South.

The magazine South as a State of Mind was used as a platform for documeta in 2017. I loved this idea – South a State of Mind, not only as a geography or location. One of my idols, one of the people that marked my doing, was Lygia Clark and the entire group of Brazilain artists of the particular Tropicalia movement; everything that was so important in the avant-garde during this time. Lygia Clark, in her performance pieces, talked about precariousness and simplicity. Precariousness was very important in what defined the South. Everything that I have participated in, the Havana Biennial that was established in 1984 exposed the art that was being made in the South that we were not considering in the North. I was very young at that moment, and it was an eye-opener to an entire production of art that was not [previously] considered of substance. That particular Biennial reframed the conversation about that. Remember it was followed later by Magiciens de la Terre [at Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris], by “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art at MoMA [Museum of Modern Art, New York]. In Cuba, [from the second edition in 1986] we were seeing works from Africa, from the Middle East, from India, from places that nobody [in the West] was previously interested in.

I met Marina Fokidis, who was the editor of the magazine “South as a State of Mind”at documenta 14. When launching the EADJ in 2018, I invited Olu Oguibe, Adam Szymczyk and Holland Cotter. And what you have is an artist, a curator and a critical voice. I maintained the same idea that started in GASP – invite a curator and ask them how do you see your ideas in relation to other thinkers of your time. So Marina Fokidis was invited as a curator for the fall series and the spring of 2021. What I’m trying to do is something that we don’t have an answer for yet. I am very much a believer – in this idea of South-South – that what has been pointed out to us as deficiencies and limitations could come back as our advantage points, that we can use to absorb knowledge, which we just need a language and systematic implementation for. My question is how do we improve social design in society as a whole? I don’t have the answer but for me this is a central question in EADJ.

The last episode of EADJ is a good example of how I’m thinking forward. Here you have an anthropologist, an archaeologist, a director of a museum, a lawyer, and they are all talking about repair or how to fix, together, a piece of pottery. Let’s use that piece of pottery for a symbol of our broken planet.

Carrie Mae Weems, RESIST COVID TAKE 6!, a series drawing awareness to how racial inequities have manifested in the COVID-19 pandemic, with people of colour inordinately at risk of the virus.

Carrie Mae Weems, RESIST COVID TAKE 6!, 2020. Digital banner. Photo: Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons. Jean Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt

The geography, the frontier of all our fights is the body – we are born, live and die in geography and this is why the South is so important in this conversation of circularity.

SS: In the series, you say that artists are the ones who write the true history of our own human outcome. I’m interested to know how this manifests in your own artwork and if you see this as your mission? You also say, “we are not doing anything new, we are continuing the fight that is not done yet”. Apart from discussion and discourse, what do you feel can be done in this fight?

MMCP: As an artist I have a calling, I’m responding to an ancestral call. bell hooks said “love is action”. Love is not saying “I want to love” – you do things to manifest your love. You do things to prove the materiality of your love. The EADJ is love materialising itself in this capacity. I consider this conversation part of my work as an artist. I am an artist first. Art is the materiality of our most sacred experience. I always start my classes with the idea that everything that we know about our human condition is because it was written in the language of art, a novel, a song, a drawing, a dance. We have become the humans that we are because art has led us this way.

Art and science, the two fundamental things – poetry and reason – they are both about imagining something and going to do it. The process, the methodologies of what we are, how we progress, are similar. Art is a fundamental, quintessential, centering, core of our humanity. The future is going to free us from labour… maybe not ours, but the future of our descendants, if we heal this planet, will mean more time to think, more time to dream. When we have more time to think and more time to dream, art is at the centre. And, what is the fight for democracy? The right to live, the right to exercise your freedom to be full in your potentiality as a human. Human rights end in the topography of the body. If I don’t have the right to own this body and express it in all its potentiality, what is a human right? The geography, the frontier of all our fights is the body – we are born, live and die in geography and this is why the South is so important in this conversation of circularity. And my entire body of work is dedicated to answering this question. Whether I am doing a drawing, a spoken piece, a performance, a painting, a sculpture, an installation – or if I am founding EADJ. I see EADJ in my question about what is the role of an artist as social designer. In this question of social designer, I want to imagine myself as a woman in the academy who is proposing a new possibility of learning and teaching.

SS: In the recent EADJ fall series, you also spoke about Trump refusing to condemn white supremacy and undermining the democratic process in the US. Is it perhaps important that you are having these conversations in Tennessee, where there is overwhelming support for Trump, rather than say the East and West coasts where you’ll likely find a level of confirmation bias?

MMCP: There is a very important conversation going on in the world right now about democracy. America is a place where democracy has played a fundamental role. When I said to you in the beginning that me being in the South is destiny perhaps, [I was taking into account how] Tennessee has a very complex history. This is the state where the Ku Klux Klan was born, and it’s a region with a very dark history. But this is also the region where some of the most important gestures of the civil rights movement took place. It’s also a place of the birth of great ideas and gestures. A few blocks from where I am speaking to you now, in 1964, people were in the street of West End avenue fighting for the right to be equal. How powerful. The fight for equality and justice that Black and some white people have fought is exemplary, and is a light that has a literary shine for so many places. So this history of light and this history of dark, and incredible sorrow and incredible joy; I grasp the joy, the determination for enlightenment and for survival. And I feel too that Nashville and Vanderbilt and Frisk and the Fritz Museum, with the medium of conversation, set in this location, in the South, can start a new conversation for the future. I see EADJ as a catalyst to really lead a conversation for how we think of a new beginning for the future, in our own collective planetary South.

Credits

Many thanks to María Magdalena Campos-Pons and Vanderbilt University