Exploring the work of Curator Özge Ersoy

Thinking through curatorial practice, writing and archiving.

Conversations about curatorial practice, pedagogy, writing, archiving and the interconnection between these frameworks for memory, identification and interpretation are ever-evolving. The COVID-19 pandemic has presented moments of increased intensity in how, where and with whom these conversations take place, with the digital environment front and centre. The past year has also offered opportunities for pause and reflection, both in one’s own personal capacity and across the globe.

Özge Ersoy is a curator and writer; Public Programmes Lead at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong; and the Managing Editor at m-est.org. Her work interrogates sociopolitical milieus while thinking through the threads that exist between exhibition-making, text, archival practices and collecting. SOUTH SOUTH interviewed Ersoy to find out more about her practice and to get a peek at the list of publications that have been her companions over the past year.

Jiang Zhuyun, Sound of Temperature, 2005. Video documentation of performance, 7 minutes 40 seconds. Installation view of “Learning What Can’t Be Taught,” AAA Library, Hong Kong, 2021. Photo: Kitmin Lee.

Julien Bismuth, Mime Works I–IV, 2010. From the exhibition Mime Works from the Gensollen Collection, with performances by Gregg Goldston, collectorspace, Istanbul, 2013. Photo: Sevim Sancaktar.

SOUTH SOUTH (SS): Could you please share a bit about your own practice and overview of your journey within the art world?

Özge Ersoy (ÖE): I’ve been based in Hong Kong since 2017, working as Public Programs Lead at Asia Art Archive, a nonprofit arts organization dedicated to contributing to a more generous and more inclusive art history. We have a library and a collection of primary and secondary materials around recent art in Asia, which has grown over the past twenty years to over 100,000 records, through numerous research and community efforts across the region. It’s important that these materials are freely accessible for research and public use from our physical space in Hong Kong and also from our website.

I’ve been grateful to be part of a team and to work closely with a community of researchers, artists, and educators who are committed to ask: how does an archive preserve materials through sharing and storytelling? In collaboration with my colleagues and our partners, I’ve been developing exhibitions, talks, and workshops exploring our research interests, including less visible histories around performance art, art pedagogy, art writing, and exhibitions, among others.

Questions around collecting and participation were also central to my work at collectorspace, which is an Istanbul-based nonprofit initiative I ran together with Haro Cümbüşyan before I joined Asia Art Archive. We organized exhibitions in a 20 square-meter storefront space: each exhibition featured a single artwork that we borrowed from a contemporary art collection. We produced public programs, publications, and video interviews around these artworks and the collections they came from. Our goal was to find creative ways to provoke discussions on collecting. We were a team of two and worked with artists, collectors, and writers who ask questions such as: how do you collect live art? How do you reinterpret traditional ideas of ownership if you acquire ephemeral and non-object-based artworks? How do you end a collection?

For over a decade, I’ve had the opportunity to work in and learn from various artistic communities in Istanbul, New York, Cairo, and Hong Kong to develop these questions. And most recently, I worked as part of the curatorial team of the 13th Gwangju Biennale, Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning, developing public programs with Artistic Directors Defne Ayas and Natasha Ginwala, with a focus on collective intelligence, antisystemic kinship, and the feminist legacy of democratization movements from the 1980s onward.

13th Gwangju Biennale website. Image: Özge Ersoy.

In collaboration with my colleagues and our partners

I’ve been developing exhibitions, talks, and

workshops exploring our research interests,

including less visible histories around performance art,

art pedagogy, art writing, and

exhibitions, among others.

SS: How do you like to describe your approaches to writing and curation?

ÖE: Writing, editing, and publishing have been part of my curatorial practice since I decided to work in the contemporary art field. My education is in political science and international relations—I haven’t formally studied art or art history. Writing, as much as exhibition-making, is a crucial tool for me to learn about art, to research, organize my ideas, and think together with artists. The most recent long-form article I wrote is “Truth or dare? Curatorial practice and artistic freedom of expression in Turkey,” published in Curating Under Pressure: International Perspectives on Negotiating Conflict (Routledge, 2020), edited by Janet Marstine and Svetlana Mintcheva. This is the result of five years of conversation with artists and curators.

I’m lucky to work with an incredible editorial team at Asia Art Archive (Shout out to Paul C. Fermin, Karen Cheung, and Chelsea Ma here). Together we develop ideas as an extension of AAA’s public programs, such as a conversation with Phoebe Wong about collections, rivers, and distributed ownership; a conversation with curator and educator Vasıf Kortun about art institutions and their publics, and most recently a conversation with AAA’s Managing Editor Paul C. Fermin about publishing cultures, conceptualizations of “Asia”, and care and community during the pandemic.

Also, one of the most rewarding projects I’ve been involved in as an editor is m-est.org, which is an online publishing platform initiated by artist Merve Ünsal. Merve and I sustain this platform for ‘slow publishing’ as we’d like to call it. We see m-est.org as an extension of our long-term conversations with artist friends. For instance, artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu, Merve and I started discussing the control artists would like to have over their work after death, and later we initiated a series called “Vasiyetimdir” (“It is my will that…”). Designer Esen Karol contributed with one sentence (“There shall be no typos in my death notice”); artist Erdem Taşdelen made a sound collage with “let go” sentences he collected from popular music songs; and an anonymous artist friend shared the colophon of a free cultural work/book that is created with free/libre software, just to give few examples.

Asia Art Archive website. Image: Özge Ersoy.

m-est.org website. Image: Özge Ersoy.

SS: What have been important thematic considerations in your recent work?

ÖE: Since 2020, I’ve been working on several programs around art pedagogy. Last spring, we started an online conversation series called Life Lessons, inspired by the way artists rethink existing structures for education, community, and care, especially with the drastic changes we’ve all gone through with the pandemic. Some examples include Melati Suryodarmo and Ming Wong speaking about traditional performance forms in Asia that influenced their teaching practice and the types of kinships they’ve developed around their work, and Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh and Zeyno Pekünlü discussing collectivity as a form and method of learning, and the role of the university as both an enabler and an obstacle in developing collective pedagogical models.

Most recently, I co-curated Learning What Can’t Be Taught hosted at AAA Library, with Anthony Yung who has been spearheading AAA’s research about art education in China from the 1950s onward. Through a selection of artworks, archival materials, and interviews, we tell a story of six artists from three generations who were each other’s teachers and students at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou—Jin Yide, Zheng Shengtian, Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Jiang Zhuyun, and Lu Yang. We ask how the foundations of contemporary art in China, which is often studied through exhibitions and artist collectives in the late 1970s and 1980s, can be traced back to the previous generation of artist-educators. You can see our text that was recently commissioned by Art & Education (Shout out to Anthony for being an amazing collaborator).

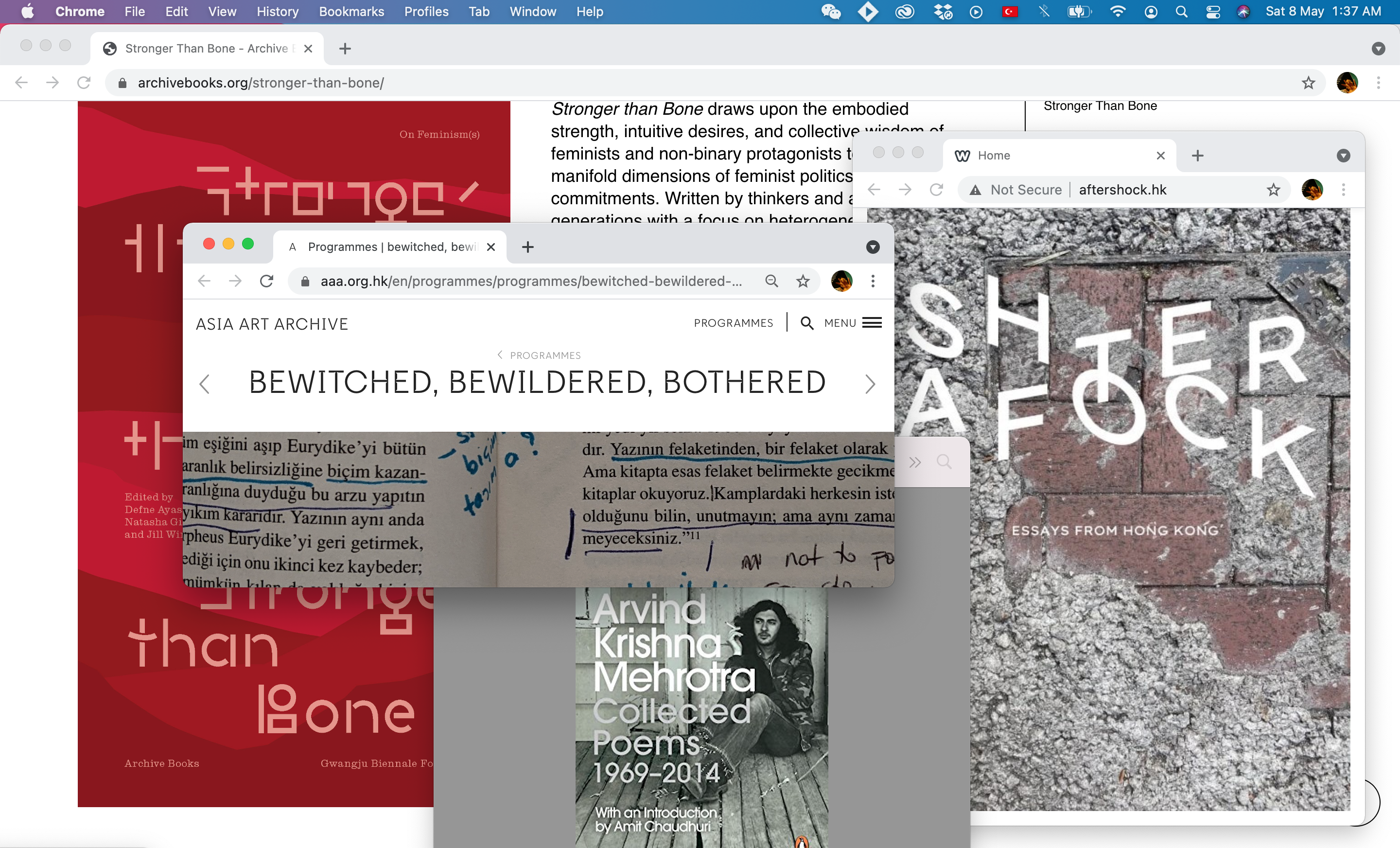

Currently, I’m working with artist Banu Cennetoğlu on a publication and a series of talks and film screenings around the politics of posthumous archives. Titled bewitched, bewildered, bothered, this project is Banu’s artistic contribution to Asia Art Archive’s exhibition Portals, Stories, and Other Journeys curated by Michelle Wong, which recently opened at Tai Kwun Contemporary in Hong Kong. With this project, we look at art’s contested claims and repeated attempts to recover the lost, to remember the forgotten, to resurrect the dead, or to speak for the silent. I hope some of you can join us for the online conversations with the artist Jill Magid and the philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado in mid-June.

Teachers examining works submitted for admission, Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, 1977. Photograph (reproduction). Zheng Shengtian Archive, AAA Collections. Installation view of “Learning What Can’t Be Taught,” AAA Library, Hong Kong, 2021. Photo: Kitmin Lee.

SS: What are the 5 publications that have inspired, challenged and uplifted you in the past year?

Stronger than Bone (Gwangju Biennale Foundation and Archive Books, 2021): This is a reader on feminism(s), and its title draws on a Sappho poem: “May I write words more naked than flesh, stronger than bone, more resilient than sinew, sensitive than nerve.” Edited by Defne Ayas, Natasha Ginwala, and Jill Winder, this book features key historical texts, poems, and newly commissioned essays by writers such as the anthropologist Seong Nae Kim who writes on women’s testimonial burdens and shamanistic rituals following the Jeju massacre of 1948; the philosopher Djamila Ribeiro who introduces the role of Brazilian Black feminism in the current political debates; and the researcher Maya Indira Ganesh who discusses her feminist take of cyborgs and bots. I’m inspired by this reader, especially in this time of fragility, vulnerability, and mourning.

AFTERSHOCK: Essays from Hong Kong (Small Tune Press, 2020): Edited by Brian Holmes, this is a compilation of essays by eleven young journalists about recent developments in Hong Kong. These are not simply journalistic pieces but intimate essays in which the authors share how they covered the news and how they’ve been dealing with the transformation of the city at a personal level. They provide a nuanced and generous discussion around the ideas of witnessing, care, resilience, grief, guilt, and exhaustion. It’s published by an independent publisher based in Hong Kong, whose work I admire.

The Share of the Silent (Sessizin Payı) (Metis Kitap, 2015): This is a compilation of essays by literary critic Nurdan Gürbilek, which explores literature’s attempts to speak on behalf of the dead. Artist Banu Cennetoğlu introduced me to this book and it has become central for our conversations about how authors/artists question their authority to give voice to the dead. Banu and I are thrilled to work with Victoria Holbrook to translate a chapter, “The Orpheus Double Bind,” from Turkish to English, and we’ll publish a book with this translation as part of Banu’s project bewitched, bewildered, bothered, on the occasion of Asia Art Archive’s Portals, Stories, and Other Journeys exhibition. Here’s a little snippet: “The threshold that separates the dead from the living cannot be crossed. Eurydice’s radical otherness cannot be represented. What has died in Eurydice cannot be resurrected in Orpheus. If one can speak of authenticity in literature, its one source is this consciousness of failure.”

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra: Collected Poems 1969–2014 (Penguin, 2014): This is one of the books I revisited over and over again this year. It features Mehrotra’s published and unpublished poems and also a selection of his English translations from the ancient Prakrit language, Hindi, Bengali, and Gujarati, including poems by Kabir, the 15th-century mystic poet, and Mehrotra’s contemporaries like A. K. Ramanujan, among many others. Here are three different translations of the same excerpt from Songs of Kabir, which shows Mehrotra’s brilliance with language: “How could the love between Thee and me sever?” (Tagore) “Why should we two ever want to part?” (Robert Bly) “Separate us? Pierce a diamond first.” (Mehrotra) (Thank you, Sneha Ragavan, for introducing me to Mehrotra’s work.)

Gathering: Political Writing on Art and Culture (National University of Singapore Press and ArtAsiaPacific Foundation, 2019) This is an anthology of essays by the Manila-based art historian, curator and cultural theorist Marian Pastor Roces, with texts published between 1974 and 2018. In a key essay Roces discusses the notion of “gathering”—gathering as “a summoning up of energies and urgencies,” “a keenness toward concealed knowledges,” and “toughness and humility.” I was thrilled that she participated in an online panel for the 13th Gwangju Biennale, where she added that her words don’t only offer poetry but also point at necessary political acts.

Image: Özge Ersoy.