SOUTH SOUTH FILM

Yinka Shonibare CBE

21 – 24 January, 2022

Films will launch Friday 21 January at 8am GMT. All films will remain active until Monday 24 January 8am GMT.

“What I find interesting is the idea that you cannot define Africa without Europe. The idea that there is some kind of dichotomy between Africa and Europe – between the ‘exotic other’ and the ‘civilized European’, if you like – I think is completely simplistic. I am interested in exploring the mythology of these two so-called separate spheres, and in creating an overlap of identities.”

– Yinka Shonibare CBE

Artist courtesy Goodman Gallery and Stephen Friedman Gallery

Un Ballo in Maschera, 2004

32 minutes looped

HD colour video,

Copyright Yinka Shonibare CBE, All rights reserved

Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball), by Yinka Shonibare, is a visually resplendent and seductive union of dance, costume, sound, history, drama, light, and architecture.

Read More

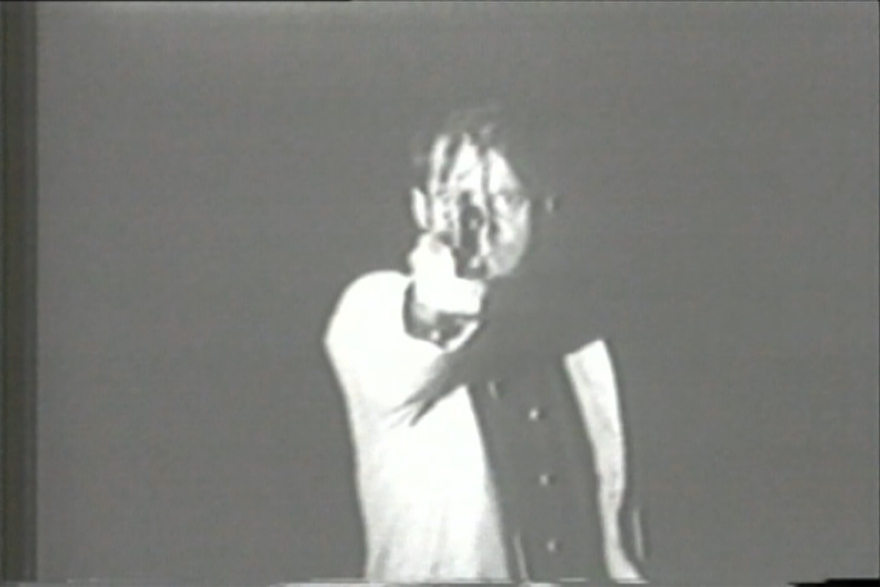

Loosely based on the opera of the same name by Giuseppe Verdi (which in turn was based on the play by Eugene Scribe who fancifully based his own play on the life of King Gustav III of Sweden [1746-1792]), Shonibare’s film takes off from the final act of the Verdi opera. In the culmination of a comparatively simple opera plot, Gustav organizes a masked ball at the Royal Swedish Opera House, a building he conceived of and had built, where he knows assassins will be waiting. Gustav tempts fate and believes himself safe due to the masks that all will be wearing. This of course turns out not to be the case.

Just as Scribe and Verdi took major liberties with the facts of Gustav’s life, adding a completely invented love story, turning run-of-the-mill political intrigue into an archetype of Romantic drama, Shonibare provocatively re-imagines the story as well. The protagonists of monarch and assassin are female rather than male, upsetting expectations of traditional gender and power roles. The 18th-century-derived court costumes that so beautifully swirl and dart throughout the film are made from Shonibare’s signature brightly colored, intricately detailed cloth. Such cloth plays a major role in Shonibare’s art, and he has dressed numerous figures in it for over a decade in static tableaux. The cloth was made in India as a Dutch imperial product sold to African markets, and has (ironically) come to signify Africa in the popular visual culture. In reality it was not made in Africa at all, pointing to a creation of identity with commercial origins. Perhaps most startlingly for a work based on an opera, there is no music, just the sounds the figures make as they dance and move through a stunning 18th-century Swedish building that was King Gustav’s rural retreat.

The narrative is in two parts: the scenes leading up to the assassination, and then those same scenes played in reverse, only to start over again on a continuous loop. The glamorously evil conspirators appear after a series of breathtakingly sumptuous dances, and one of their members shoots Gustav; the crowd reacts, yet within a moment Gustav is seen rising again, and the film plays backwards, including the sound. Shonibare is following in the tradition of structuralist film makers of the 1960s and 70s, whose disruption of tradition and continuity was meant to bring awareness in viewers that film itself is entirely a construct, no matter how naturalistic it may seem. He can also be seen as alluding to Gustav’s peculiar character trait (in the Verdi opera) that defies danger and recklessly continues; in Shonibare’s version, Gustav gets to have his ball and fulfill his dramatic role, but his death is only temporary and the pleasure that we have witnessed starts in all over again.

Perhaps more pointedly Shonibare’s work suggests that history always repeats itself, and that the colonial project of Europe is cyclical. Former subjects of the British Empire return to England to create a hybrid culture. Shonibare himself was born in London in 1962 but raised in Nigeria. He came back to London to attend school and remained there at a moment of intense artistic ferment in that city in the late 1980s and throughout the 90s. In dressing his characters in such recognizably contemporary “African” garb, Shonibare effectively is representing his own history as a person of African background making art within the highly ordered social structures of the former colonial power of England. Yet that colonial power’s history is, for better or worse, also Shonibare’s own, and he is a person deeply rooted in Western cultural forms of aesthetics and address, making such a work as this instinctively familiar yet somehow new

Read Less

Odile and Odette, 2005

14 minutes 28 seconds

HD digital colour video, sound

Courtesy the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and James Cohan Gallery, New York. Commissioned by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 2005

Odile and Odette (2005-2006) is a film made in collaboration with the Royal Opera House. Here, Shonibare re-imagines a classical episode from Tchaikovsky’s Ballet Swan Lake, where the lead roles ‘Odile’ and ‘Odette’ engage in a close dialogue of gestures and movement.

Read More

Odile and Odette are characters which embody “good” and “evil” and are traditionally danced by a sole prima ballerina. The artist transforms this classical part into a complex and subtle interplay between two dancers in which the duality of the characters is played out in racial difference. Mirroring each other’s expression on either side of an ornate Baroque frame, Shonibare suggests that their movement is both estranged and united. The dancers perform a passage from the ballet in a studio stage set to silence, the rhythm of their pointe shoes creates the only soundtrack to the film.

Filmed from one side of a “stage set” but using two cameras, the doubling effect is further played out as the dancers switch sides of the mirror frame and creates a visual environment where the viewer is privileged to see the work performed from both sides of the ‘mirror’. The film’s narrative and construction suggest that both characters are one and that their complex relationship is both co-dependent and formed by each other.

In a recent interview Shonibare said: “What I find interesting is the idea that you cannot define Africa without Europe. The idea that there is some kind of dichotomy between Africa and Europe – between the ‘exotic other’ and the ‘civilized European’, if you like – I think is completely simplistic. I am interested in exploring the mythology of these two so-called separate spheres, and in creating an overlap of identities.”

Read Less

Addio del Passato, 2011

16 minutes 52 seconds

Digital video, colour and sound

Copyright Yinka Shonibare CBE, All rights reserved

Addio del Passato (2011) is the title of an aria about betrayal, love and loss from Verdi’s opera La Traviata, sung by the dying heroine Violetta. In this film Shonibare alters the characters so the aria is performed by a black singer in the guise of Frances Nisbet, the wife who Nelson betrayed and abandoned during a lengthy affair with Lady Hamilton. Read More Here Nisbet agonizes over her own life and Nelson’s absence, even envisaging his death in a series of tableaux (the Fake Death Pictures) that occur outside the immediate action of the film, as though giving form to her tortured thoughts and daydreams. Addio del Passato is Shonibare’s first investigation of Nelson’s wider human story; more typically he views Nelson in a purely metaphorical sense, as a cipher for empire. As an artist he works with aesthetics, metaphor, politics; indeed, his headless and faceless figures are purposefully not “individuals” with whom we could identify as people. As such, despite its obvious artifice, the level of emotional intensity and engagement offered by Addio del Passato is unexpected, breathtaking. Like Un Ballo in Maschera (2004), this work features what at first seems to be the looping of the film. However, this is not a loop, but an actual live replaying, the singer beginning her song and her walk through the house and landscape again. In this case the repeated action implies an endless cycle of sadness and despair that amplifies the potency of feeling and sense of hopelessness. The film explores the concept of destiny as it relates to themes of desire, yearning, love, power and sexual repression. The film was shot in the magnificent surroundings of Syon Park, just outside London, which is the ancestral home of the Duke of Northumberland. Originally built in the sixteenth century, it was extensively remodeled in the eighteenth century by two of the most renowned designers of the period to reflect contemporary fashions – Robert Adam working on the house and Capability Brown on the landscape. This location extends Shonibare’s reference to the aristocracy and the trappings of wealth. Read Less

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Yinka Shonibare CBE (b. London, UK, 1962 -) studied Fine Art at Byam Shaw School of Art (1989) and received his MFA from Goldsmiths College, London, (1991).

His interdisciplinary practice uses citations of Western art history and literature to question the validity of contemporary cultural and national identities within the context of globalization. Through examining race, class and the construction of cultural identity, his works comment on the tangled interrelationship between Africa and Europe, and their respective economic and political histories.

In 2004, he was nominated for the Turner Prize and in 2008, his mid-career survey began at Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; touring to the Brooklyn Museum, New York and the Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C. In 2010, his first public art commission Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle was displayed on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London, and was acquired by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

In 2013, he was elected as a Royal Academician and was awarded the honour of ‘Commander of the Order of the British Empire’ in the 2019 New Year’s Honours List. His installation ‘The British Library’ was acquired by Tate in 2019 and is currently on display at Tate Modern, London.

His work is included in notable museum collections including Tate, London; the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C.; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Guggenheim Abu Dhabi; Moderna Museet, Stockholm and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.