SOUTH SOUTH FILM

Minerva Cuevas

24 – 26 September 2021

Films will launch consecutively starting Friday 24 September at 8am GMT. All films will remain active until Monday 27 May 8am GMT.

Through the intervention of images and objects of daily consumption, Minerva Cuevas invites us to rethink the role corporations play in food production and the management of natural resources. Employing irony and humor, her work seeks to provoke reflection about the impact that local actions can have on the enforcement of fair labor practices and the redistribution of monetary flow. Cuevas’ practice encompasses a wide range of media, including painting, video, sculpture, photography and installation, through which she investigates the politics and power structures that underlie specific social and economic ties.

Artist courtesy kurimanzutto

Not impressed by civilization

2007

colour video transferred to DVD

13 min 20 sec

The performance — which formed part of the piece as a whole — consisted of spending one night outdoors in the Rocky Mountains in northeast Canada.

Read More

(*) Tatanka Iyotanka (widely known as Sitting Bull) was not impressed by European white society and its version of civilization. During his travels in the 19th century, Tatanka was surprised to see the number of homeless people living in American cities. As a leader who influenced his tribe to not yield indigenous lands, he became an enemy of the forces of colonization. Tatanka Iyotanka was killed by his own people; enlisted indigenous police officers influenced by the power of colonizers. This tactic continues to be used against indigenous leaders throughout the American continent.

Read Less

The Poor Man, the Rich Man and the Mosquito

2007

DVD

4 min 10 sec

I: A rich man once lived opposite a poor man. Everyday, through his window, he saw how poor he really was. He said to himself: “What have I in common with this man?”

Read More

Now he was dying.

And the rich man across the way who saw him every day said to himself:

“What have I in common with this man?”

And the poor man was dying. Dying.

He was hated by everyone, for to everyone money he owed. He was feared by everyone because everyone, afraid of the fever, feared his physical approach. He was languishing, no flesh and only bones, unable so much as to bear his own weight. He sweats and sweats, trembles and trembles. He was dying, thinking of his inventions, raving about strangely, blazing forth numbers and then more numbers.

He was dying, alone as can be.

And the rich man across the way saw him every day from his window and, stingy, he once again said to himself, “What have I in common with this man?”

But then that same night one of the millions of mosquitoes that lived in a swamp bit the dying man.

Later, flying at the mercy of the shadows, it gained entrance to the home of the rich man, who was sleeping, and bit him too.

As the mosquito bit him, it passed on the disease of which the poor man was dying.

And the rich man was no longer able to see the poor man from across the way from his window.

II: Both men died of the same affliction, both died practically at the same time, unaware of what the one had in common with the other. Underground practically at the same time, they were left to the worms practically at the same time, alone as can be. And, to this day, those worms remain unaware of who was the rich man and who was the poor man.

And what about the mosquito? Whatever happened to the mosquito? Whomever else did it bite? Whomever else will it bite?

One can’t really say. One can’t follow a mosquito into the shadows. Maybe it still flies along at night, buzzing its eternal jest. Filling up on all sorts of blood, it injects one man’s blood into another. One can’t really say one way or another. The only thing set in stone is that there will never be a shortage of the thousands of types of mosquitoes whose singular mission is to show us that it is not in our best interest for there to be wretches amongst us, that to help them in due time means to help ourselves. It means that whichever mosquito bites them in the future will not in turn ruin our lives.

The only thing set in stone is that there is never a shortage of mosquitoes, nor of even more minute beings, there to violently remind us of that which men of the heart should already know, that we all have much, very much in common with our neighbours, particularly when our neighbours are dreadful wretches.

– Tomas Meabe

Read Less

Disidencia v 2.0

2008-2010

single-channel HDV projection with sound, colour

25 min 43 sec

For several years now Minerva Cuevas has been mapping opposition in Mexico City by recording both its more evident and its inconspicuous signs as part of a video archive.

Read More

Through places and time and along with a wealth of demonstrations and direct political references we are granted access to the subtle and many times invisible or clandestine ways of how resistance can manifest. One of the highlights of this portrait of the city’s rebellious character are the rural elements that remind us of the city’s origins and that constitute a form of resistance by themselves, managing to defeat the urban definition of a city.

Disidencia v 2.0 resembles a personal cartography where Cuevas puts in the map an ethic of resistance.

Disidencia’s visual archive is accompanied by 2 musical compositions by Mexican composer Pablo Salazar.

Read Less

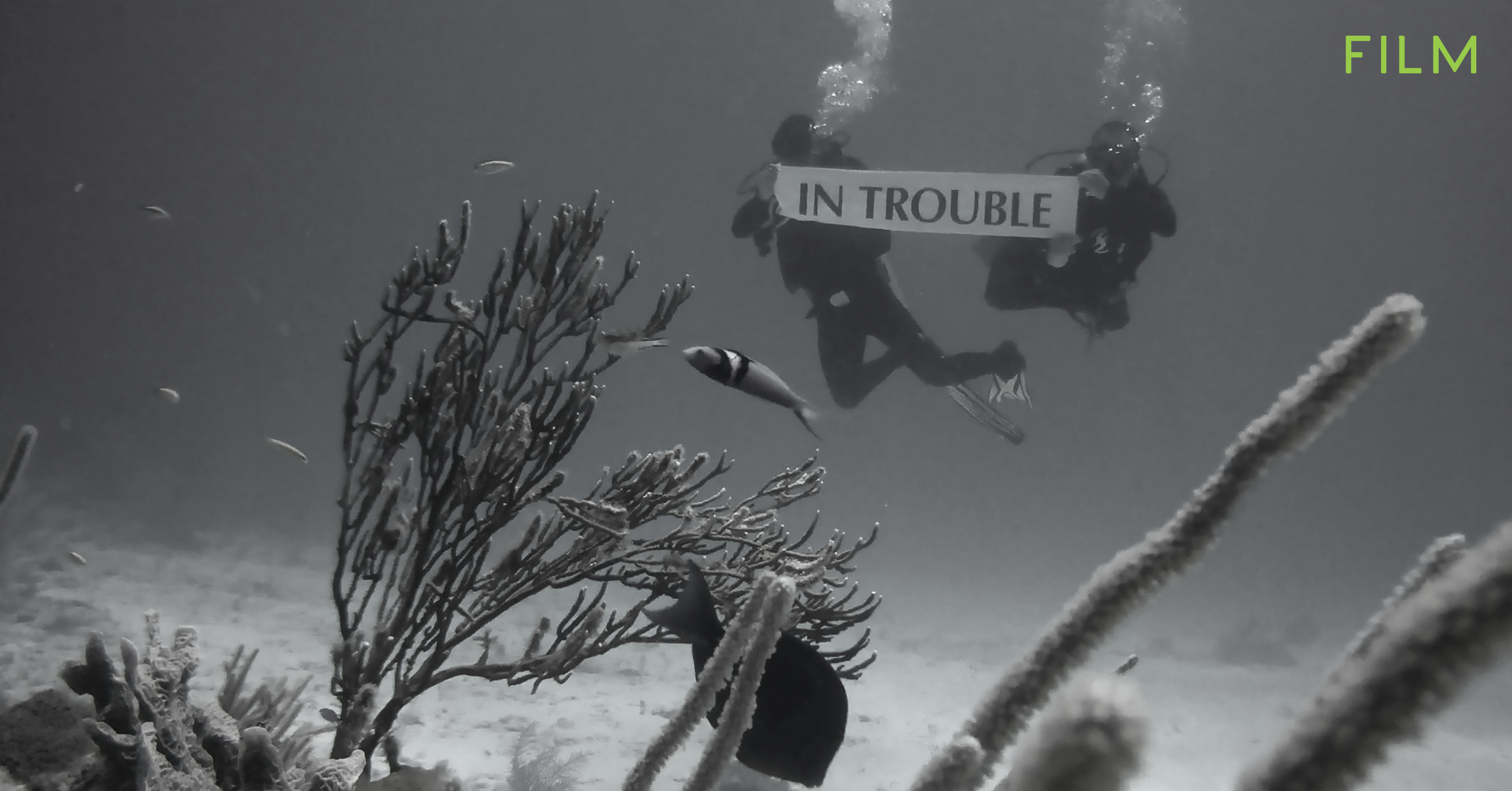

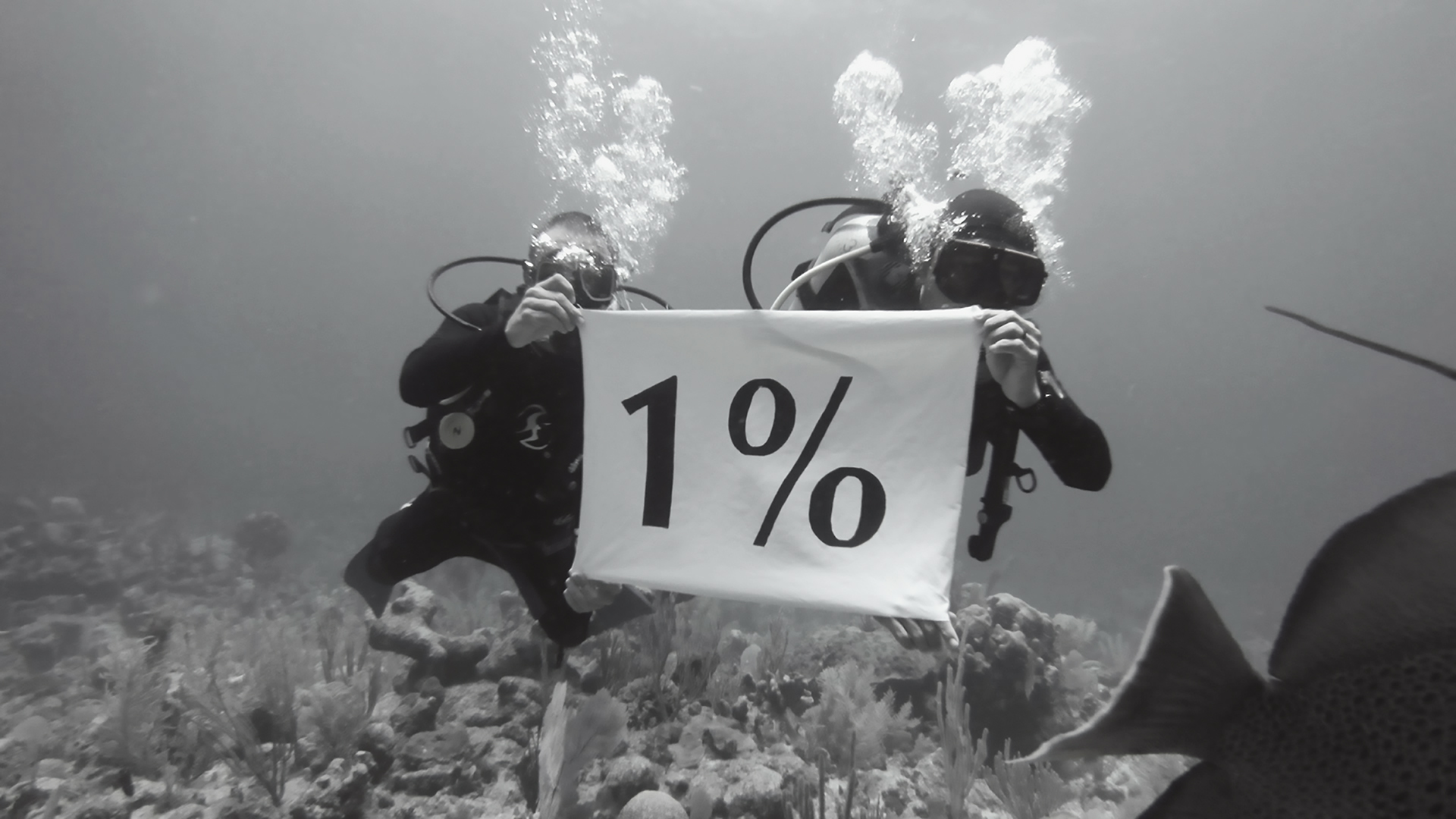

A Draught of the Blue

2013

HDV, colour, sound

9 min 48 sec

Minerva Cuevas researched and produced this screen-based work off the coast of Akumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico, an area that is part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef system –unique in the Western Hemisphere for its size, biodiversity, and the types of reefs it includes. It is globally important and under severe threat.

Read More

Minerva Cuevas researched and produced this screen-based work off the coast of Akumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico, an area that is part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef system –unique in the Western Hemisphere for its size, biodiversity, and the types of reefs it includes. It is globally important and under severe threat. In addition to the life they support, reefs serve as natural barriers, protecting coastal communities and beaches. Their survival is critical to the economic livelihood of millions of people throughout the world.

In this work, as underwater demonstration becomes a central image for Cuevas, as she explores the possibilities of assuming social rights, capacities, and agency in relation to the present social and environmental crisis.

Cuevas’ analysis centres on the real risk posed by rising sea levels for the coastal populations of the area of Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz and Guerrero.

Read Less

No Room To Play

2019

video HD projection, sound, colour

6 min 29 sec

No Room to Play is a single channel video projection in German with English subtitles. It expands on Cuevas’ environmental and sociological research, contemplating the real world of issues of climate change in what she views as façades of democratic states. No Room to Play is not a post- apocalyptic fiction, it is a pre-apocalyptic admonition about economic, environmental and urban decline.

Read More

Initially a camera pans over an abandoned naturalistic playground, like some kind of imagination grove envisioned by Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian social reformer. It is a desert island in an urban landscape. There is a mix of equipment and structures spread across a sand foundation that looks “organic” to the point of crunchy: non-toxic, safe and eco- friendly. There are over-sized carved and painted wooden animals, vegetables and playhouses among the equipment and water feature.

No human is present in this play space. Their only traces are footprints in the sand and graffiti on walls. The park is surrounded by apartment buildings in an urban landscape. The film is accompanied by a score of chimes, which are initially soothing and inviting, before becoming dissonant, accompanied by neurotic percussive clicks and drumbeats. The visuals are at first meditated through color filters, changing like seasons with the story line.

Read Less

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born in 1975 in Mexico City, through the intervention of images and objects of daily consumption, Minerva Cuevas invites us to rethink the role corporations play in food production and the management

of natural resources. Employing irony and humor, her work seeks to provoke reflection about the impact that local actions can have on the enforcement of fair labor practices and the redistribution of monetary flow. Cuevas’ practice encompasses a wide range of media, including painting, video, sculpture, photography and installation, through which she investigates the politics and power structures that underlie specific social and economic ties. Her interdisciplinary projects combine aspects of anthropology, product design and economics to explore different ways of intervening urban spaces, museums and galleries. Whilst appropriating the language of the establishment (branding, advertisement and commerce) the artist delivers a message of non-compliance and resistance. A relentless critic of reality, Cuevas discovers her source material through analyzing the notions of value, exchange and ownership that rule a capitalist economy –as well as their consequences. Her work serves as a tool to discuss the condition of the individual under a capitalist regime: constant abuse, dispossession and estrangement from ancestral and cultural identity, but also the latent possibility of revolt implicit in the everyday.

Minerva Cuevas studied BA in Visual Arts at Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in Mexico City. In 2004, she was recipient of the Grant for Media Art of the Foundation of Lower Saxony at the Edith-Russ-Haus. She was artist in residence at the Berliner Künstlerprogramm en Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) in 2003 and Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, in 1998.

Recent selected solo exhibitions include: No Room To Play, DAAD Galerie, Berlin (2019); Disidencia, The Mishkin Gallery, New York (2019) & Galpao VB, Sao Paulo (2018); Minerva Cuevas, DMA Dallas Museum of Art, United States (2017); Minerva Cuevas, Museo de la Ciudad de México, (2012); Landings, Cornerhouse, Manchester, United Kingdom (2011); SCOOP, Whitechapel Gallery, London (2010); Minerva Cuevas, Van

Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands (2008); Phenomena, Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland (2007); On Society, MC Kunst, Los Angeles (2007); Egalité 2007, Le Grand Café – Centre d’art contemporain, Saint-Nazaire, France (2007); Schwarzfahrer Are My Heroes, DAAD Galerie, Berlin (2004); Mejor Vida Corp, Museo Tamayo, Mexico City (2000).

Cuevas has exhibited in numerous international group shows, such as: Soft Power, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) (2019); Down and to the Left: Reflections on Mexico in the NAFTA Era, Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, United States (2017); We call it Ludwig, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany (2017); Unsettled, The Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, United States (2017); Under the Same Sun: Art from Latin America Today, South London Gallery, (2016), Museo Jumex, Mexico City (2015) & Guggenheim Museum, New York (2014); United States of Latin America, MOCAD Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, United States (2015); Food: dal cucchiaio al mondo, MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del

XXI secolo, Rome (2015); Sportsmanship under surveillance, LACAP – Latin American-Canadian Art Projects, Toronto, Canada (2015); Testigo del siglo, MAZ – Museo de Arte de Zapopan, Mexico (2014); In/Humano, MARCO – Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey, Mexico (2014); Utopian Days, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, South Korea (2014); Resisting the Present, Museo Amparo, Puebla, Mexico (2011) & Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris (2012); Elles, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2010); Populism, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (2005); Hardcore, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2003); among others.

She has also participated in the following biennials: Prospect 4, Nueva Orleans (2017); 6th Liverpool Biennial, United Kingdom (2010); 6 Berlin Biennale (2010); 9e Biennale de Lyon, France (2007); 6th Bienal do Mercosul, Porto Alegre, Brazil (2007);

27a Bienal de São Paulo (2006); Sharjah Biennial 7, United Arab Emirates (2005); 14th Biennale of Sydney (2004); 2nd edition of the T.I.C.A.B – Tirana International Contemporary Art Biannual, Albania (2005); 8. Istanbul Bienali (2003), Turkey.

Minerva Cuevas lives and works in Mexico City.